Inside Uber’s unsettling alliance with some of New York’s shadiest car dealers

Geovanie Rosario signed the lease because it was easy. Tower Auto Mall came recommended by Uber, as one of four dealers the ride-hailing company partnered with in New York City to offer “flexible and affordable” rentals and lease-to-own contracts to drivers. Rosario went to see Tower one morning in May 2016 and started driving a black Lincoln MKS, New York City’s standard car-service vehicle, a week later. His contract included a $3,000 service fee and weekly payments of $495 for 159 weeks, or just over three years. Tower would take the payments directly out of his Uber earnings every Monday.

Geovanie Rosario signed the lease because it was easy. Tower Auto Mall came recommended by Uber, as one of four dealers the ride-hailing company partnered with in New York City to offer “flexible and affordable” rentals and lease-to-own contracts to drivers. Rosario went to see Tower one morning in May 2016 and started driving a black Lincoln MKS, New York City’s standard car-service vehicle, a week later. His contract included a $3,000 service fee and weekly payments of $495 for 159 weeks, or just over three years. Tower would take the payments directly out of his Uber earnings every Monday.

Rosario had quit his position as an assistant manager at Rent-A-Center, a job with benefits and a 401(k), to drive for Uber in March 2015. Rent-A-Center paid $12.25 an hour, and, based on Uber’s ads, he figured he could double that by becoming a driver. He had tried a couple of car rental options and, by the time he went to Tower, felt confident he could make enough to come out ahead.

But a month into his lease Rosario fell ill with pneumonia. He tried to keep driving, worried his payments would pile up, but he couldn’t control his cough. With no health insurance, it was hard to get treated, and what little money he did make went straight to his lease. It was late June when Rosario felt well enough to start working full-time again. By then he was $1,800 in debt. When he tried to start up the Lincoln, its alarm sounded.

“That’s when I realized they’d turned the car off,” Rosario said. He called Tower to ask why the dealer had remotely deactivated his vehicle. “They said, ‘You have to make a payment.’”

Uber upended the global, $100 billion taxi market, achieving a valuation of nearly $70 billion, with an app that hails a car at the touch of a button. But the company still struggles to recruit and retain the more than 1.5 million drivers worldwide who make that business possible.

It has attracted them with hefty signup bonuses and the promise of good pay, then cut rates and increased its own commission. It has advertised “being your own boss” but glossed over the fact that independent contractors don’t get benefits or a guaranteed minimum wage. Uber has been sued repeatedly by drivers who allege they were misclassified as contractors rather than employees. It settled with the US Federal Trade Commission earlier this year for misleading drivers about their potential earnings. It paid back tens of millions of dollars to drivers in New York City in May after admitting it for years shortchanged them on wages.

In recent months, Uber’s treatment of drivers has been almost completely forgotten amid a series of internal scandals. The company has lost nearly a dozen top executives so far this year, including founder and CEO Travis Kalanick, following multiple allegations of sexual harassment and workplace misconduct. It fired more than 20 employees as the result of a harassment probe in early June. Kalanick stepped down on June 20 after five major shareholders demanded his immediate resignation. He has retained a seat on Uber’s board of directors.

As it desperately tries to right itself, Uber has turned to its drivers, long a source of its harshest criticism. The same day Kalanick resigned, the company launched a campaign to improve the driver experience, titled “180 Days of Change.” But some of its past practices towards those drivers might be difficult to untangle.

In July 2015, Uber launched its Xchange Leasing subsidiary to finance leases and rentals for drivers in the US with poor or no credit. The program has been criticized for its sky-high terms and potential for taking advantage of workers, though Uber said it was designed to streamline and improve financing options for drivers. But two years later, Xchange has yet to become available in New York, one of Uber’s oldest, largest, and most profitable markets. Instead, the company has maintained partnerships with a small network of third parties that predate its leasing subsidiary, and which operate in the underbelly of New York’s auto-financing market, without much scrutiny.

Now, after being questioned by Quartz, Uber says it will pause referrals to its partners as it investigates the program.

“Last week, we made a commitment to drivers: to fundamentally change their experience with Uber for the better,” Uber said in a statement. “We take that commitment seriously, which is why we are halting referrals to third-party vehicle leases as we conduct a comprehensive audit of the third-party leasing program in New York City. We will not hesitate to make any changes necessary to fully honor our commitment to drivers.”

Uber operates in 76 countries and more than 450 cities, but it is uniquely strict in New York City about what types of cars are allowed. To get drivers in the city on the road with an Uber-approved vehicle, the company has encouraged people like Rosario to sign auto-financing contracts that create a relationship somewhat akin to indentured labor. The rentals and leases that Uber recommends carry weekly payments as high as $500. They also require the driver to sign a “payment deduction authorization” that lets the dealer or lessor take fees directly out of their Uber earnings, effectively garnishing their wages. Leasing a car with the intention of buying it—“lease-to-own”—typically takes three years, over which time a driver might pay for his vehicle two to three times over.

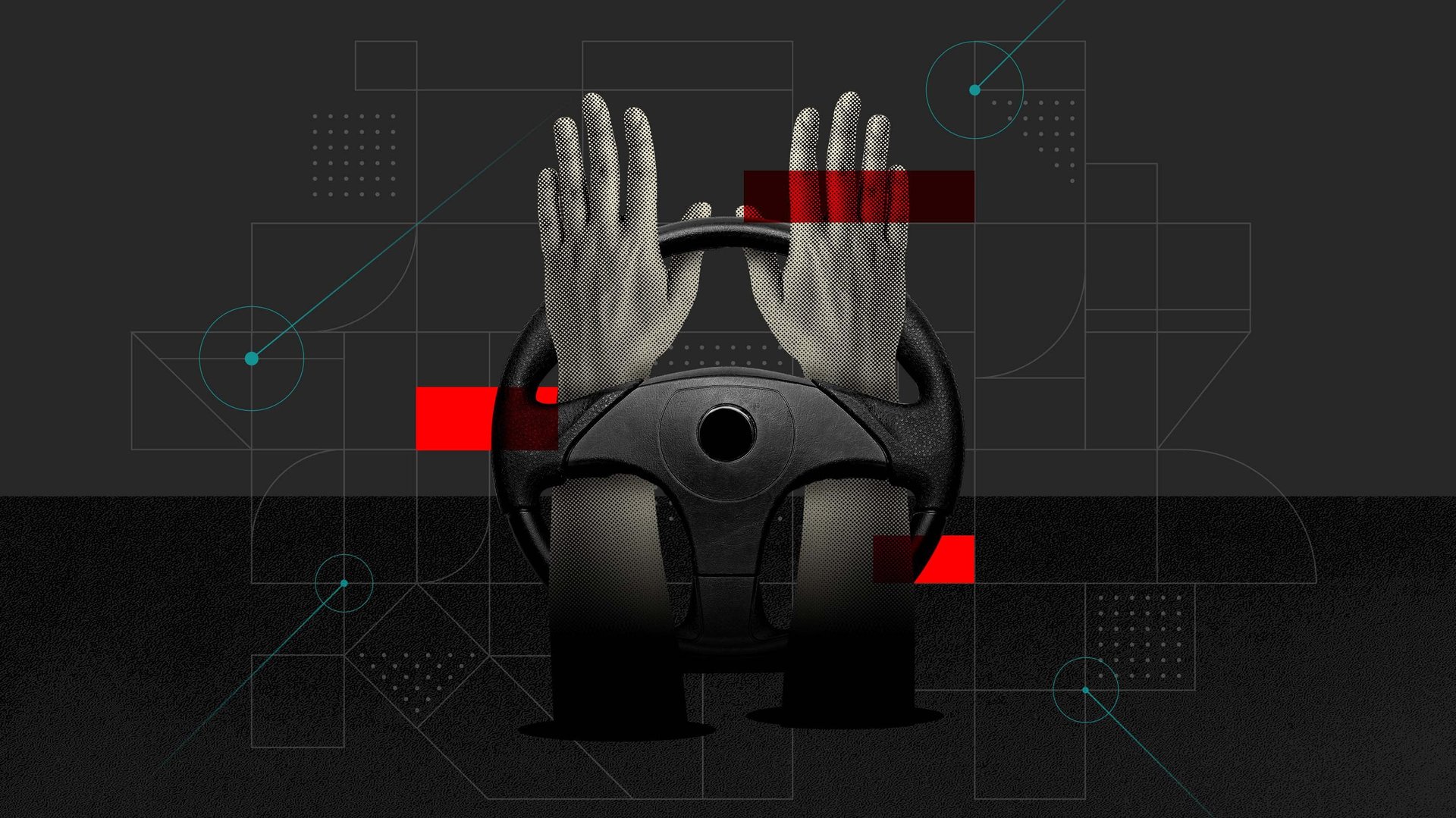

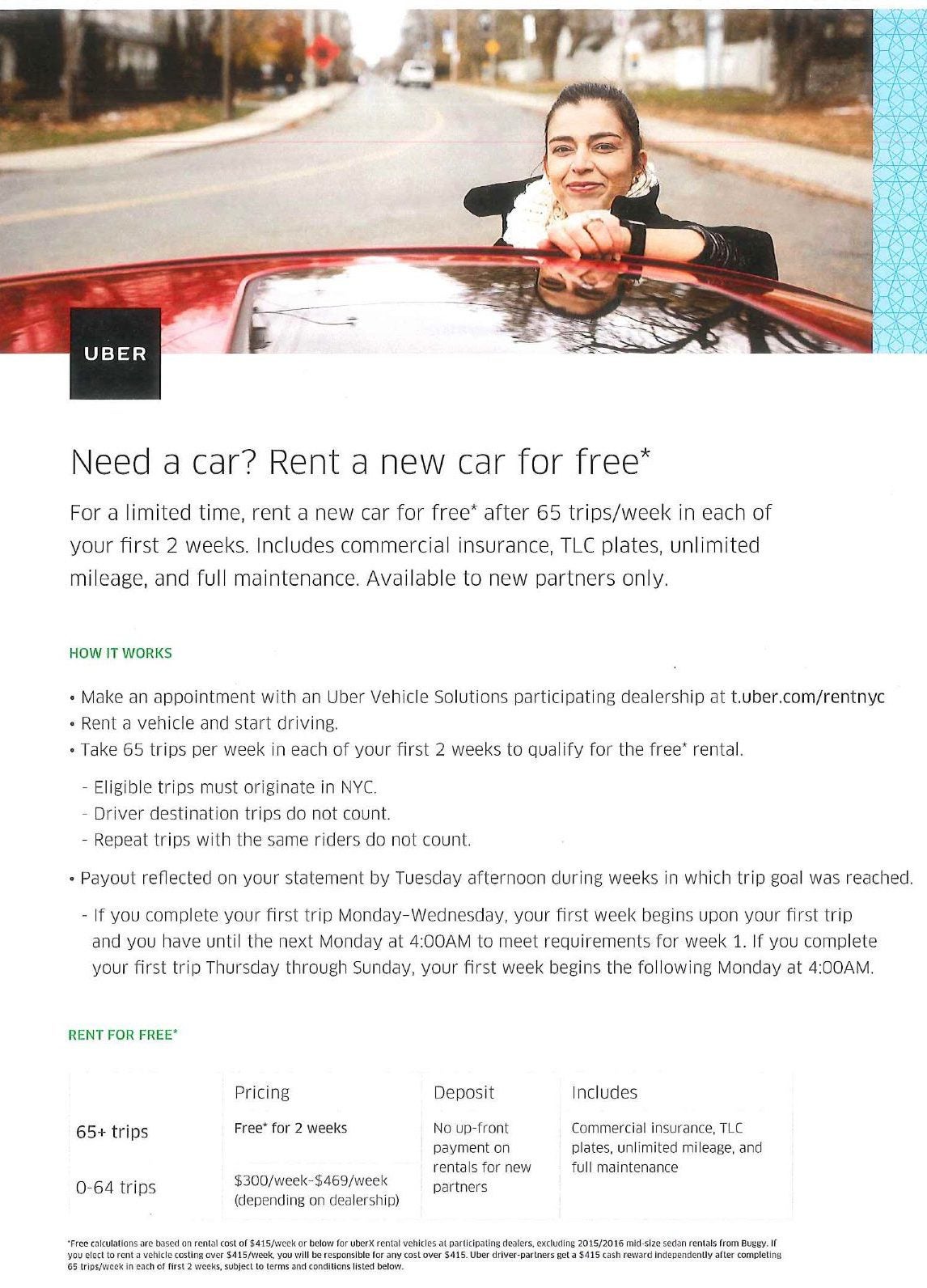

On the “vehicle solutions” section of its New York website, Uber recommends four dealers—Tower, American Lease, Buggy TLC Rentals, and Fast Track Lease—as the “quickest way to get a car.” It describes the weekly rentals as “flexible” and says that with lease-to-own, “you pay less per week.” Drivers who visit one of Uber’s Greenlight Hub service centers receive a glossy black folder with a printout that advertises renting a new car “free” from a participating dealer, or visiting the Uber website to learn more about lease-to-own, a “long term option with vehicle ownership at the end.”

Ninety-plus percent of professional drivers in New York City are immigrants and driving can be one of the few opportunities they have to earn money. The auto dealers Uber partners with target people with poor credit who otherwise might not be able to buy a car or get a loan. Uber, through its ads and signup process, has given drivers every reason to believe that these lease and rental contracts are a good choice. The reality can prove otherwise.

“Uber tells you, you can do this job when you feel like,” said Marion Wolfe, a former Uber driver and lessee in New York. “That’s not true. When you’re locked in with these leasing companies, you’ve got to go out there and make that money. You have to be out there and hustle to make that rent money for the car.”

I first met Rosario in late January at a meeting of the Independent Drivers Guild, a non-union group that represents Uber and other ride-hailing drivers in New York City. I arrived late to the meeting, around 9pm, and explained to a small audience that I was researching a story on people who lease cars to drive for Uber. Rosario quickly agreed to talk to me about his experience with Tower. “It was definitely double what it was worth,” he said of his lease that night. He sent me a copy of the paperwork provided by Tower, “summary of lease to own agreement,” a few weeks later.

At the time Rosario signed his lease with Tower, a 2015 Lincoln MKS was selling new for $45,292, according to data from auto research firm Edmunds. Rosario agreed to pay nearly twice that for a car that came with 14,000 miles (22,500 km) already on it. The weekly payments of $495, which included the cost of insurance but not repairs or maintenance, totaled $78,705 over three years. An additional $3,000 for a “non-refundable service fee” brought the total to $81,705. At the end of the term, Rosario had the option to purchase the car for $1.

The lease explained that the $495 a week was a special rate, discounted from $525 for Uber drivers, and available “for as long as Lessee drives using the UBER Technologies, Inc. (‘UBER’) service.” It didn’t specify how often the driver needed to work for Uber to meet those standards, just that the car must be affiliated with an Uber base—a locally licensed dispatch center—at all times during the lease. Uber told Quartz those terms are decided by the dealer.

Uber approached Tower and several other dealers about setting up partnerships between 2013 and 2014 to help its thousands of newly licensed drivers get cars, a source familiar with the matter told Quartz. At the time many drivers were paying $450 to $600 a week to rent a car licensed as a for-hire vehicle with the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission, the local taxi regulator, the source said. By offering dealers a steady stream of business and the security of payments facilitated by Uber, the company hoped it could also convince them to lower their rates.

Uber launched in New York in May 2011. The company told Quartz it began partnering with third-party dealers in July 2014 and does not take a commission or fee from the lease payments. It declined to specify how many drivers currently rent or lease their cars in New York through its four partner dealers, but said a “very small percentage” of drivers are in lease agreements. “New York City drivers who want to lease a car so they can earn with Uber are referred to dealers that offer competitively priced leases,” the company said in a statement. “We plan to review any complaints drivers have about these dealers.”

Uber’s leasing practices were referred to the New York state attorney general about two years ago, and the office has privately expressed interest in probing the matter, a source familiar with the matter told Quartz. The AG’s office did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Tower is a servicer that manages auto loans day-to-day for leasing companies, which provide the actual financing. It produced Rosario’s contract on behalf of CB Livery Leasing, a company based in the Bronx and established in February 2015, according to papers filed with the New York Department of State. These days, Tower executes about 200 car contracts a month, most of them to Uber drivers, said Sazid Rahman, a sales consultant. Uber is the only ride-hailing company Tower is officially partnered with. Rahman said Tower makes these sales “regardless of credit” so long as the applicant has professional driving experience.

Rosario had no credit when he went to Tower to see about getting a car. The dealer told him it offered a non-credit plan that was less affordable and required weekly instead of monthly payments. After that, he said they didn’t ask about his assets or income, “just that I had a bank account and worked for Uber.” He paid $2,000 of the $3,000 service fee upfront, and the rest at a rate of $100 per week over 10 weeks.

Rosario’s lack of credit history put him in a category of borrowers known as “deep subprime.” Subprime auto lending is a growing problem in the US, reminiscent of the housing bubble before the 2007 crash. Over the last six years, it’s become much easier to borrow money to buy a car. The result is that the volume of auto loans made to “subprime” consumers with credit scores below 620 has soared.

In the third quarter of 2016, there were $280 billion worth of subprime auto loans in the US, according to data from the New York Fed and Equifax, compared to $188 billion in the third quarter of 2010. Of those loans, the share made to “deep subprime” consumers—those with credit scores below 550—has meanwhile climbed to 32.5% from 5.1% since 2010, according to research published in March by Morgan Stanley. Steve Eisman, the investor who famously shorted subprime home mortgages and earned a starring role in Michael Lewis’s The Big Short, is now eying subprime auto lenders.

Subprime lending can fill an important gap in the market by providing financing to people who might otherwise be unable to secure a loan. But the leases supplied to Uber drivers in New York are ripe for abuse, said Chris Kukla, executive vice president at the Center for Responsible Lending, after examining Rosario’s lease summary as well as a contract between Marion Wolfe and Buggy LLC. He pointed to a clause in Wolfe’s lease that allowed Buggy to repossess the car and report it to the police as “lost or stolen” if he missed a payment and failed to respond to communications for five days.

“That’s pretty coercive,” Kukla said. “It’s very concerning to see a contract where the lender is threatening to use law enforcement as a collection tactic.”

Predatory auto lending is as much a fixture of New York City as the iconic yellow cab industry. Long before Uber, cabbies were effectively indentured to medallion owners, who rented out the right to operate a taxi. Dealers did brisk business leasing black cars to a largely immigrant population. When Uber first came to New York it talked about freeing drivers from such practices. Instead the company has pushed more drivers into burdensome leases and rentals, and lent legitimacy to the way these dealers do business.

“It’s a very grayish situation,” Sohail Rana, an Uber driver and member of the Independent Drivers Guild, told me. “It’s good for if someone is desperate to rent a car.”

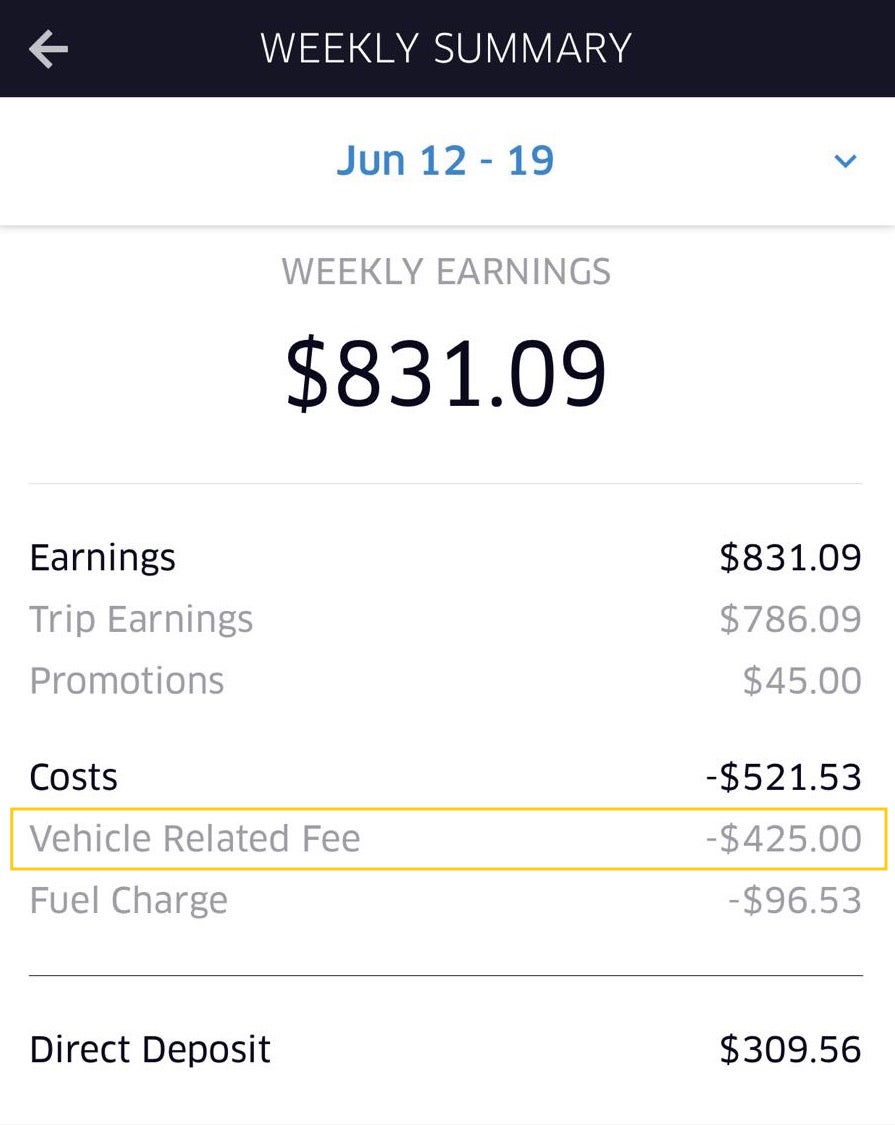

Earlier this year, Rana took a friend to Tower to see about renting a car. The friend, Muhannad Issa, had been out of work for about six months at the time and also had a baby on the way. Issa couldn’t afford to buy a car and his credit was bad. Tower had denied Issa a rental before because of an old speeding ticket, but Rana knew the owner and called in a favor. The dealer agreed to let Issa rent a car to drive for Uber for $425 per week, plus a $450 deposit. It took the money out of his Uber earnings every Monday morning. “I was telling him, this is not your best option, this is your best option of all the bad options,” Rana said.

Most Uber drivers are part-time workers. But for people who need to make a weekly payment on their car rental or lease, working part-time often isn’t an option. When Issa didn’t drive at all the week his baby arrived in March, Tower deducted the $425 straight from his bank account. He got back on the road a few days later but planned to look into other rental or lease options, “because $425 a week, that’s too much.”

Marion Wolfe got his car from Buggy, another of Uber’s partner-dealers, when he started driving for the company in March 2016. Wolfe signed up for Uber to supplement his income from a job with the New York City metro. At first he rented a car for $450 a week, but the dealer told him he could get a newer vehicle if he did lease-to-own.

Buggy, also known as Lux Credit Consultants, was set up in January 2015, according to papers filed with the New York Department of State. The office in Crown Heights, a neighborhood of Brooklyn, is surrounded by a chainlink fence with barbed wire on top. A black Uber poster board leans against the front of the building. Inside, half of the front office is taken up by a table staffed with two Uber representatives who sit against the back wall and help sign up drivers for leases and rentals. When I stopped by one afternoon in late June, one man wore an Uber T-shirt. Another had a laptop labeled “Uber Loaner 229.”

Amit Bal, general manager of the Crown Heights office, said Buggy signs more than 100 contracts for rentals and leases a month, 90% of them to Uber drivers. He estimates that two-thirds of the deals are rentals, with payments ranging from $369 to $469 a week. “We don’t deal with credit at all,” he said.

In July 2016, Wolfe signed a 156-week contract for a 2016 Hyundai Sonata, which at the time had an average transaction price of $24,332, according to Edmunds. Buggy priced the car at $158.33 a week—which over 156 weeks totals almost exactly the sale price of the car—but offered optional fees for liability insurance ($110.62), potential repairs ($80.05), and proper licensing with the city’s taxi commission ($68). Wolfe chose all of them, bringing his total weekly payment to $417. He paid $695 down plus sales tax on the full price of the car, or $2,253.76, when the contract commenced. Over the life of the lease, the payments totaled a little more than $68,000. The licensing fees alone added up to $10,608, compared to the $550 the taxi commission charges to license a car as a for-hire vehicle for two years. “Without knowing all the details of the contract, it’s difficult to respond,” said Allan Fromberg, a TLC spokesman, when asked whether those fees were unusual. “But it’s equally difficult not to say ‘wow.’”

By August, Wolfe was driving more than 30 hours a week just to stay ahead of his payments.

“I couldn’t take a day off,” said Wolfe, who has a wife and three children. “I was a part-timer and it felt like I was really pulling full-time hours.”

As of April, Uber had 600,000 US drivers who had taken at least one trip in the last 30 days. The company’s own research has found that just half of those drivers remain after one year; tech news site The Information reported the retention rate is much worse. Driverless cars are on the way but we are years if not decades from the time when they become ubiquitous. Until then, Uber’s business of providing on-demand rides hinges on its ability to keep a critical mass of drivers working on the platform.

The task is not easy anywhere, but especially in New York City. While Uber’s ascent in the city has been stunning, there is no shortage of traditional taxis and for-hire vehicles, as well as ride-hailing competitors. Lyft’s New York ridership has doubled over the last year, according to TLC data. Gett, a ride-hailing company most popular in Israel, Russia, and the UK, acquired competitor Juno in late April. Via, a shared rides service, in early June partnered with taxi-hailing app Curb to bring shared rides to New York’s yellow cabs.

Uber hires its drivers as independent contractors rather than employees to avoid having to give them benefits or a guaranteed minimum wage. Because of that, the company can’t tell drivers where or when to work, both of which risk being deemed “employer-like” by a court. It also can’t prevent them from driving for competitors like Lyft or Juno, which many do. What it has done is put more drivers on the road with financing agreements that lock them into working for Uber.

“There’s no question that they’re doing it for driver retention,” said Matthew Daus, a partner at law firm Windels Marx and former chair of the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC), after reviewing one of the leases obtained by Quartz for this story. “You have an arrangement where an independent-contractor driver’s hands are being tied to prevent them from going somewhere else.”

None of the three lease-to-own contracts that Quartz examined for this story explicitly instructed the leaseholder to work only for Uber. But in all three cases, the driver was required to agree to some form of payment deduction from his Uber earnings as a term of the lease. Rahman, the Tower sales consultant, said the deduction arrangement is “good for the drivers and good for the leasing companies” because it simplifies the payments process. Wolfe’s contract with Buggy outlined his payment terms in section six, “THE DRIVER’S OBLIGATIONS.” 1

A typical Uber driver in New York earned $23 to $24 an hour before expenses like gas in October 2015, according to the most recent figures available from Uber (the company slashed prices in January 2016). Even at the 2015 rate, Wolfe would have had to work about 18 hours just to earn enough to cover his weekly lease payment. Were his Uber earnings insufficient in any week, the contract also authorized Buggy to collect its fees from Wolfe’s bank account or to charge his debit or credit card, “both without further demand to, authorization from, the Driver.”

Rosario initially saw the deduction agreement in his contract as a plus. “I figured it was easiest,” he said. But after he contracted pneumonia, the only thing the agreement made easy was falling into debt. After Tower agreed to reactivate his car in June 2016, Rosario drove 30 to 50 hours a week, despite the lingering cough that still left him short of breath. When Rosario came up short on his payments, he said Tower would collect all his Uber earnings and also hit his bank account for the full amount. Soon his bank balance disappeared and he racked up hundreds of dollars in overdraft fees.

Such arrangements may come back to haunt Uber. In early June, the New York state labor department deemed three former Uber drivers and “others similarly situated” to be employees, as opposed to independent contractors, in a dispute over jobless payments. In her decision, administrative law judge Michelle Burrowes noted that two of the claimants, Jeffrey Shepherd and Jakir Hossain, had leased cars from a third-party dealer recommended by Uber in spite of their poor credit.

“It is notable that the claimants were restricted to use vehicles deemed acceptable by Uber,” Burrowes wrote. “Uber not only referred them to their third-party affiliates to lease vehicles without credit; but also, Uber took the additional step of withholding monies from these claimants’ fares and making lease payments on their behalf.” Uber said it does not believe helping drivers get leases with car dealers to work on its platform represents “employer-like” control.

Geovanie Rosario’s lease was harder to terminate than to sign. In early October 2016, less than six months after he secured the contract, Rosario was still about $1,300 behind on the Lincoln and he also owed rent on his apartment. He chose to pay rent and, unable to make his full lease payment, phoned Tower to say he was calling it quits. Rosario said he would drop the car off at the dealer’s office in Long Island City, worried it would charge more to have the car repossessed. When he got there, Tower told Rosario he owed $2,500 to return the car. That fee was never mentioned in the leasing paperwork he showed to Quartz.

Marion Wolfe also broke his lease with Buggy after six months. In January 2017, Buggy asked him to return the car after he missed payments for several weeks. Wolfe explained that he had fallen behind because of a death in his family, but the dealer wasn’t interested. “When Buggy told me to bring back the car I thought that might be a sign of God,” he said. Buggy charged him $2,500 for early termination, which in his case was outlined in the contract.

Muhannad Issa is still renting from Tower. After his wife had the baby, she needed multiple surgeries because of complications from the birth. Issa took off five weeks to care for her, the baby, and their two other children. With no Uber earnings to debit, Tower took the money from his bank account each week until the balance turned negative. When he called Tower and asked to defer the payments, a woman explained that wasn’t possible for rental customers, but if he wanted to lease to own, “they could do something about it.” Issa now drives 12 hours a day, seven days a week, to pay off his debts. He sent his wife and children home to their family in Jordan. “They’ll be able to help her with the baby,” he said, “and I’ll stay here and work my butt off.”

I ran into Rosario again at a TLC hearing in April. It was a cool, rainy day but every seat was occupied in the 19th-floor hearing room in downtown Manhattan. Then, as now, Uber was consumed by other scandals that had pushed its relationship with drivers from the spotlight. News had broken recently that the CEO and several other top executives had attended an escort-karaoke bar on business in Seoul; one of Uber’s self-driving cars had crashed in Arizona; Jeff Jones, a high-profile hire from Target, had resigned.

But to drivers the real issue was and has remained how Uber treats them. That much was clear at the taxi commission hearing, where one Uber driver described working in the industry as “modern-day slavery.”

Rosario didn’t plan to testify but had come to listen. In the months since he stopped leasing from Tower, Rosario had been driving for Uber by renting a Lincoln MKT for $475 a week and working under an account registered to a fleet owner. He’d never paid Tower the $2,500 return fee or the outstanding $1,300 on his balance and worried that if he signed into Uber’s app under his own name, the dealer would take his wages all over again. But the week before the hearing he’d decided to reopen his own Uber account to see what would happen.

That day at the taxi hearing, Rosario finally had some good news. “They didn’t charge me,” he said, grinning. “I’m good for right now.”