If we’ve learned anything from the European crisis, it’s that being a technocrat charged with implementing a bailout is a terrible job. Imagine how much worse it gets when your country is in the throes of revolution.

In Egypt, the military junta has appointed Hazem el-Beblawi as interim prime minister until elections planned for the fall. An economist trained in Paris, Beblawi’s main task will be trying to get the International Monetary Fund to approve a $4.8 billion loan to his cash-strapped country, and doing that will likely take some unpopular moves at a time when such actions have been met with massive street protests.

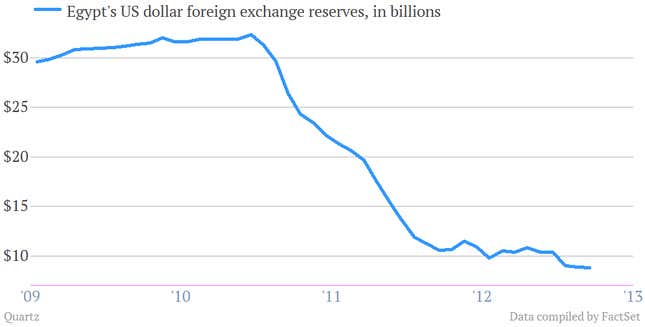

You can see all the problems that beset Egypt’s economy following the 2011 ouster of strongman Hosni Mubarak in our chartbook. But the biggest problem right now is a lack of foreign exchange; some $20 billion in reserves has evaporated since the first coup:

Those losses, along with a weakening currency, make it more expensive for Egypt to subsidize wheat imports and energy, two important policies in a poor country suffering from a downswing in tourism, the country’s economic lifeblood. Even though the cost of the subsidies make up 25% of Egypt’s budget, shortages of electricity and diesel fuel are common.

But the IMF is not interested in funding a subsidy program, and wouldn’t provide the loan to the most recently ousted president, Mohamed Morsi, because of his refusal to end the aid. That may have been smart politics for Morsi on some level, at least in the short-term, but with his departure Egypt can hardly continue down the same economic path. The military’s decision to appoint Beblawi, long a critic of Egypt’s subsidy-ridden government, is a clear sign that it will pursue the IMF loan. The question is whether its military might will be enough to maintain order if a painful reform program goes forward.

“The revolution was obliged to inform the public about the financial crisis, which did not happen,” Beblawi recently told Daily News Egypt. “The revolution’s success did not mean it was time to distribute spoils, but rather it meant that there was more work to be done, after a burden was successfully removed.”