If there’s one thing you really don’t want scattered across a highway, it’s live hagfish. But last week, five vehicles collided on an Oregon highway, flinging 7,500 pounds of hagfish—also known as “snot snakes” and “slime eels”—across the blacktop, and making a very unusual mess.

Gross as the goo may be, the highway hagfish catastrophe highlights a nagging problem. Hagfish serve an important ecological role: By gnawing apart animal carcasses like dead whales, hagfish are crucial to keeping sea floors clean and ocean ecosystems in balance. So we want to make sure to keep them around. There’s just one problem. Much about hagfish existence mystifies scientists—and has for centuries, making it hard to know whether their numbers are shrinking. And that happens to explain why 7,500 pounds of Oregonian hagfish came to be cruising down Highway 101 last week.

The miracle of slime

When Carl Linnaeus, the father of taxonomy, encountered the hagfish in 1758, he classified it wrongly, as a worm. But his description was on the money: Intrat et devorat pisces; aquam in gluten mutat (“enters into and devours fishes; turns water into glue”).

Because they have skulls, hagfish aren’t technically worms. But neither are they fishes—nor eels. These sightless, jaw-less, scale-less, fin-less creatures are basically in a category of their own, an evolutionary link connecting vertebrates and invertebrates. Over the course of 330 million years, the hagfish has barely changed, with one notable exception: It developed slime glands. Thanks to the marvelous goo these emit, hagfishes have little to fear from most predators or competitors. When threatened, the slime they spew chokes predators, gumming up their mouths and gills. This reflex is likely why when the flatbed truck carrying them crashed on Highway 101 they secreted their special goo—the poor little guys panicked.

These sometime-scavengers feed on sunken carcasses from the inside, entering through the dead animal’s mouth or anus. Then they tunnel through muscle and viscera with their tooth-lined tongues, until nothing but skin and bones is left. (Fishermen tell of hauling up prime catches like cod only to find nothing inside them but glutted hagfish.)

The slime also helps hagfish protect their meals. As they feed, their gelatinous gunk swathes the carcass, sealing it off from other scavengers, as marine biologist and blogger Andrew David Thaler explains.

Thanks to soldiers and scientists interested in using the slime to pioneer things like petroleum-free plastics, ballistics protection, anti-shark spray, and super-strong fabrics, we understand a fair amount about hagfish goo. Their sex life, however, remains shrouded in mystery.

The birds and the bees and the hagfish

The confusion around hagfish mating persists despite plenty of motivation to solve it. Recognizing their evolutionary significance, in the 1860s, the Royal Danish Academy of Scientists announced a major prize rumored to take the form of a gold metal or ingot, according to the Wall Street Journal (paywall)—for anyone who solved the puzzle of hagfish reproduction. The award has never been claimed.

Hagfish have no external sex organs, which means they probably don’t do internal fertilization (but then again, they might be like coelacanths, which pull it off without the usual equipment). But we’re not sure; attempts to observe mating in captivity have proven similarly futile. One hagfish authority compares hagfish to giant pandas, in that they refuse to get it on in captivity, reported the WSJ.

To this day, no one has ever seen hagfish mate, or even trying to mate. Even finding sexually mature males and viable sperm is tricky—one study of Atlantic hagfish found live sperm in only one male out of 1,000. And females produce a relatively small clutch of eggs (around 20 to 40, depending on the species). This puts the odds of fertilization in the open ocean closer to the miracle end of the spectrum.

Then there’s the even bigger puzzle for biologists to ponder: Where the heck are the hagfish eggs?

Egg hunt enigma

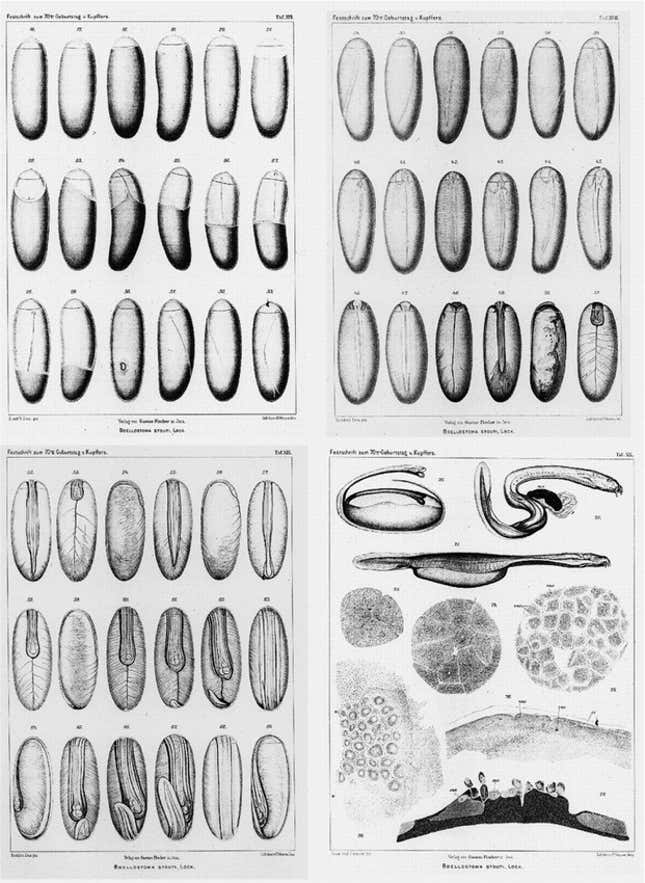

Scientists have yet to stumble upon any eggs in the wild—in no small part because we don’t even know where hagfish leave them. Though biologists have searched for hagfish eggs for well more than a century, no one has come close to the 800 eggs, including 150 embryos, collected in California in 1896 by one Bashford Dean, an expert in medieval armor who also happened to study fish. Drawings made from his collection are still the textbook standard of hagfish embryology.

Dean’s hagfish egg collection came from Monterey Bay fishermen who spent a summer dangling baited lines from rowboats. In their alarm at having been hooked, the hagfish released slime, encasing them as they struggled on the line. Stuck within those gobs of slime were the eggs.

Try as they might, no scientist since has come close to pulling off Dean’s egg-amassing feat. Throughout the entire 20th century, scientists found only three embryos.

It may be that eggs are hard to come by because they’re nestled in seafloor rocks—or maybe hagfish mate in the muddy hidey-holes of the seafloor. One eminent biologist hypothesized that couples slime each other while mating, releasing eggs and sperm that form embryos suspended in the goo (pdf, p.337). But none of these hypotheses hint how Dean hit the hagfish spawn jackpot when everyone else—including those using submersible vessels a century later—has come up short.

The riddle of hagfish reproduction isn’t just a scientific curiosity. Without knowing how, or how much, they reproduce, it’s hard to figure out if we’re catching too many hagfishes—that is, leaving fewer in the wild than are needed to replace themselves. One real-world implication of that problem is evident in the backstory of the sliming of Highway 101 last Thursday afternoon.

The hagfish bonanza begins

The Oregon crash casualties were en route to Korea, one of the only places in the world where people go goo-goo for hagfish meat (and hagfish wallets, as it happens). The creatures first emerged as a Korean delicacy during Japan’s occupation of the country from 1910 to 1945, according to CNN. The Japanese harvested hagfish to make shoes from their skins, discarding the meet for Koreans to collect and eat. And lo, the popular delicacy was born. The leather goods business boomed too; by the 1960s, hagfish skin had become a major material used in designer wallets, handbags, and other accessories.

For a while, Korean demand for hagfish meat and global demand for Korean-made “eelskin”—of which the US was a major importer (paywall)—was met by species caught in East Asian waters. But by the late 1980s, Korea and Japan had overfished their hagfish, spurring North American fishermen to fill the growing void (pdf, p.7).

Meanwhile, as US regulators took steps to prevent overfishing of groundfish on both coasts, fishermen moved further down the food chain; running a side business in hagfish gained in popularity on both coasts of North America. In Massachusetts, for instance, as the George’s Bank cod population crashed, fishermen switched their focus first to dogfish and then to hagfish, as Mark Kurlansky detailed in The Last Fish Tale: The Fate of the Atlantic and Our Disappearing Fisheries. In Atlantic Canada, hagfish landings rose 24-fold between 1994 and 2014. By the mid-2000s, New Zealanders were in on the trade too.

US fishermen used to freeze their hagfish catches at sea before shipping them across the Pacific. But as Asian hagfish populations have dwindled into nothingness, Koreans will pay a lot more for live hagfish that can be grilled fresh on demand. So Pacific northwest fishermen have taken to capturing, and transporting, their slimy quarry to port alive (pdf, p.7). Though volumes are still relatively small, the returns on hagfish landing have climbed steadily.

How many hagfish is too many?

Scientists and some fishermen fear that, without solving the mystery of hagfish reproduction, the US and other countries could unwittingly follow Korea and Japan in blotting out their hagfish populations. (There’s some concern that this already might be underway in New England, where hagfish catches collapsed after their 2000 peak.)

So what happens to the sea if there are too few hagfish? No one is sure.

It’s likely that a dearth of hagfish would mean more dead animals—including the astronomical volumes of bycatch discarded by fishermen—left to decay on the seafloor. Mucking up the environment could hurt other fish, particularly bottom-hugging fish like flounders, haddocks, and cod. In fact, there’s some evidence (paywall) of this happening in New England. The build-up of rotting carcasses would also alter the nutrient and chemical mix of the ocean, making it inhospitable for some creatures, and inviting others to thrive—and warping marine ecosystems in the process.

Too few hagfish could also be bad for the food chain. While hagfish eat huge quantities of deep-sea worms, they also serve as tasty meals for seals and other marine mammals (which apparently don’t mind a mouthful of slime).

To protect hagfish populations in the face of all the unknowns, several US states have made moves (pdf, p.7) to monitor their fairly unregulated hagfish fisheries. In the meantime, they might want to think about some tiny seat belts, too.