The New York Times should accelerate the shift underlined in its latest quarterly results: reconsidering the daily print product and moving aggressively abroad.

The quarterly earnings season always shows valuable trends in the media industry. As murky as the New York Times financials are, especially when compared to many tech companies, their quarterly statement for the second period of this year confirms one thing: it is time for bold moves at the New York Times.

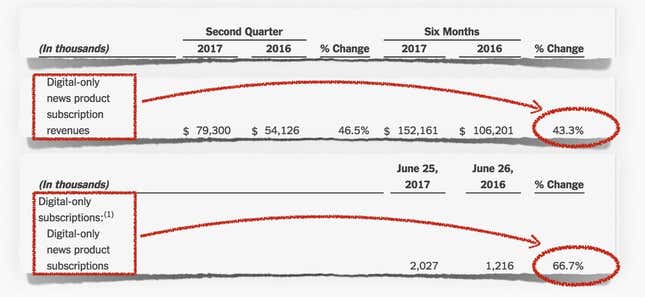

See the following data points:

These figures merely confirm what previous quarters told us: Print is crumbling, both in terms of advertising revenue and circulation. Unsurprisingly, weekday print sales decline much faster than the iconic Sunday edition—substantially helped by an arrangement giving the least expensive digital access to its subscribers. Too bad the New York Times Company does not provide a break down for weekly vs. weekend advertising revenues. If, as I suspect, the weekend edition accounts for more than 50% of the of the publication’s print ad revenue, this would make the case for discontinuing the week’s daily print edition. Here is why:

How do you know an industry is right to be disrupted? It raises its prices faster than the inflation. You can argue that media or television are much likely to be disrupted: they raise the price while their viewership has gone down.

- As mentioned in previous quarterly statements, the improved revenue stream for print comes largely from a price hike for newsstand copy sales and subscriptions. This signals a dying business. Says NYU Stern’s marketing professor Scott Galloway:

- This is exactly the case for the print media. Worldwide (OK, except in India).

- Discontinuing most of the New York Times’ print business would be a huge cost saving: most of the twenty-plus company-owned printing plants (such ownership is an absurdity in today’s economics) would be phased out and replaced by leased facilities—up-to-date ones better suited to print a neat, journalism-gratifying product that, as importantly, is ideally-designed to accommodate upmarket advertising. Such modernized print product will be much more profitable than today’s one-pound, greasy, leaflet-laden product. A no-brainer.

- Whether for the Times or other legacy newspapers, it is nearly impossible to assess the real benefit of curtailing print operations. Depending on their agenda, your interlocutors will serve you the data that fits their views.

- Therefore, offloading the least profitable part of the print operation is more a question of managerial conviction than of objective analysis that can be bent every which way. On this, my take is the vast majority of publishers will wait until the last possible moment to make the move. We know how that usually ends.

- Given most news companies’ enduring print culture, I don’t see any publisher bold enough to actively anticipate the inevitable. (Contrast this with Northern Europe where painful but healthy reforms took place in the early 2000s.)

Coming back to New York Times specifics, another required move is international expansion.

Here is what New York Times CEO Mark Thompson said in July 27th’s earnings call (emphasis mine):

In closing, I’d like to comment on our remarkable international growth. In the past year, our digital subscriptions have soared and The New York Times now has subscribers in 195 countries. International subscribers make up 14% of our over 2 million paid digital-only news subscriptions and continue to grow at a faster rate than our domestic additions. In fact, international subscriptions grew 80% compared with the same period last year. But we also believe that we have only begun to tap the potential for subscribers and advertisers beyond our domestic market.

Fourteen percent. That’s good, but not exactly the global reach the Times craves for. By comparison, 88% of Facebook users are outside the US domestic market, and they account for 51% of its revenue. To be sure, this is an extreme example—the Times isn’t Facebook. But the global reach of the BBC could be the real beacon for New York Times (or the Washington Post, for that matter, which repeatedly said it wants a global footprint).

Here is the pitch that Mark Thomson, Meredith Kopit Levien (EVP and chief revenue) and, some day, Arthur Gregg (A.G.) Sulzberger, who will take the reins of the empire (the sooner, the better), could make to their troops:

Folks, first, congratulations for the outstanding year-to-year growth—80% for Q2 2017—on our international subscriptions. It’s a great performance. It shows strong potential.

But we need to move faster, much faster. Let’s me set some parameters here: The worldwide market for English-speaking, college-educated people is about 500 million people. The BBC currently captures about 30% of it, some 150 million people. Of course, you might object that the BBC only offers a free product and say there is no way we’ll get these 150 million people to pay even half of the US price for the digital New York Times.

But keep in mind the following: here, each digital subscriber brings about $145, in total about $300 million a year in revenue. Now, if we were able to enroll only 10% of the BBC’s audience, that is 15 million people. How much could we reasonably charge them? My guess is we should consent to a 75% discount. Yes, I know, that’s a lot. It is equivalent to an Average Revenue per User (ARPU) of $36 per year, or $3 per month, net for us. By the way, I’m not picking the 75% discount out of thin air: when Facebook makes one dollar in advertising in the US domestic market, it brings, as an average, only 25 cents in the rest of the world. For the New York Times Company, such a large discount applied to this high-volume recruitment campaign would bring an additional $500 million per year to our revenue stream. Our subscription revenue would reach a cool $800 million per year… And I’m damn sure we can convert more than 10% of Beeb fans…

Of course, this fictitious speech is full of holes.

Convincing regional audiences to buy a New York Times subscription, even a heavily discounted one, would require beefing up the production of regional news, increasing the number of foreign bureaus (currently 24), and creating an ultra-dense network of contributors (The Washington Post has put together a network of 3,000 trusted contributors worldwide).

Similarly, the sales network would need to be much more granular, with a mix of direct investment and local alliances. Or it could shift to a completely different approach, more based on Facebook or the Google sales interface that allows them to sell ads with unparalleled efficiency on any market.

Another factor is the New York Times’ current spread of topics, which, besides our traditional news mix, is largely made of niche markets such as food and lifestyle. Are these worthy to focus on, or are they mere distraction?

The Times must also consolidate and manage its domestic subscription growth: last quarter’s spectacular performance should not conceal disturbing facts. Consider the table below:

The increase in digital news subscriptions revenue on a year-to-year basis (+43%) is substantially lower than the actual number of new subscribers (+67%). The influx of new subscribers is largely due to the “Trump bump” that every serious American news outlet currently enjoys; it might not last forever—even if we’re all flabbergasted by Donald Trump’s endless ability to feed the news cycle with his insane presidency. Even in this flourishing period for subscriptions, The New York Times brought home 14% less per subscriber than a year ago. As a comparison, during the same period, Facebook increased its ARPU by 24% globally and by 35% domestically. This divergence is another illustration of the widening gap between the economics of platforms and media.

For the two bold moves I suggest (phasing out the printed daily and aggressive international expansion), we also need to factor in the peculiar culture of legacy media. Downsizing print entails putting a dent in the newspaper’s magisterium. From the masthead to the newsroom trenches, no one will easily abandon the print’s noble status.

As for a massive foreign expansion conquest mode, it will collide with the product’s perceived value: I don’t see anyone at the New York Times accepting a 75% discount for international markets subscriptions, even if IP-based geo-blocking techniques could make it easy to implement, and even if Facebook has been doing it for a long time. (When Facebook makes 100% per user in the US and Canada, it makes 31% in Europe, 12% in Asia-Pacific, and only 8% in other countries). To take a subscription-based global business, Netflix applies a differential of 3:1 between its richest and poorest markets (that is a nominal value—it actually varies with exchange rates). Again, this is a Rubicon that tech companies—governed by data and growth obsession—have long crossed while legacy media stay on the bank (of the river, I mean), and wait.