Uber is beginning to warn drivers about “long trips” likely to last over an hour

Uber driver Steve Fleck wasn’t expecting to drive to Cincinnati when he picked up a passenger at the MGM Grand Detroit a few minutes after 5:30am on Aug. 2. The ride-hailing company doesn’t reveal rider destinations to its drivers until after they accept a trip, a feature designed to keep drivers from discriminating against customers headed to poorer and less accessible neighborhoods historically underserved by taxis. But that Wednesday morning it also meant Fleck didn’t learn his rider had booked a four-hour trip across state lines until the passenger was already climbing into his car.

Uber driver Steve Fleck wasn’t expecting to drive to Cincinnati when he picked up a passenger at the MGM Grand Detroit a few minutes after 5:30am on Aug. 2. The ride-hailing company doesn’t reveal rider destinations to its drivers until after they accept a trip, a feature designed to keep drivers from discriminating against customers headed to poorer and less accessible neighborhoods historically underserved by taxis. But that Wednesday morning it also meant Fleck didn’t learn his rider had booked a four-hour trip across state lines until the passenger was already climbing into his car.

“I was a little in shock,” Fleck, 37, said.

Uber is now testing a feature to avoid precisely these situations. “Long Trip” warns drivers when a ride is likely to last over an hour before they accept the fare. The feature was spotted by Harry Campbell, author of the popular driver blog The Rideshare Guy, as well as on Reddit, where one driver recently shared a screenshot of the alert. “Long: This trip likely to take 60+ minutes,” it reads. A spokesman for Uber confirmed to Quartz the company is testing this feature. He declined to say whether refusing a long trip would count toward a driver’s overall ride acceptance rate.

Fleck’s 265-mile trip took a little over four hours and 10 minutes. The rider slept most of the way, then chatted with Fleck for the last hour. Fleck said the rider asked for his contact information, in case he wanted to make the Detroit to Cincinnati trip by Uber again. The rider left a small tip, which Fleck took to a cafe down the street after completing the trip. He took a short break to eat a curry chicken sandwich, then turned around and drove back to Detroit.

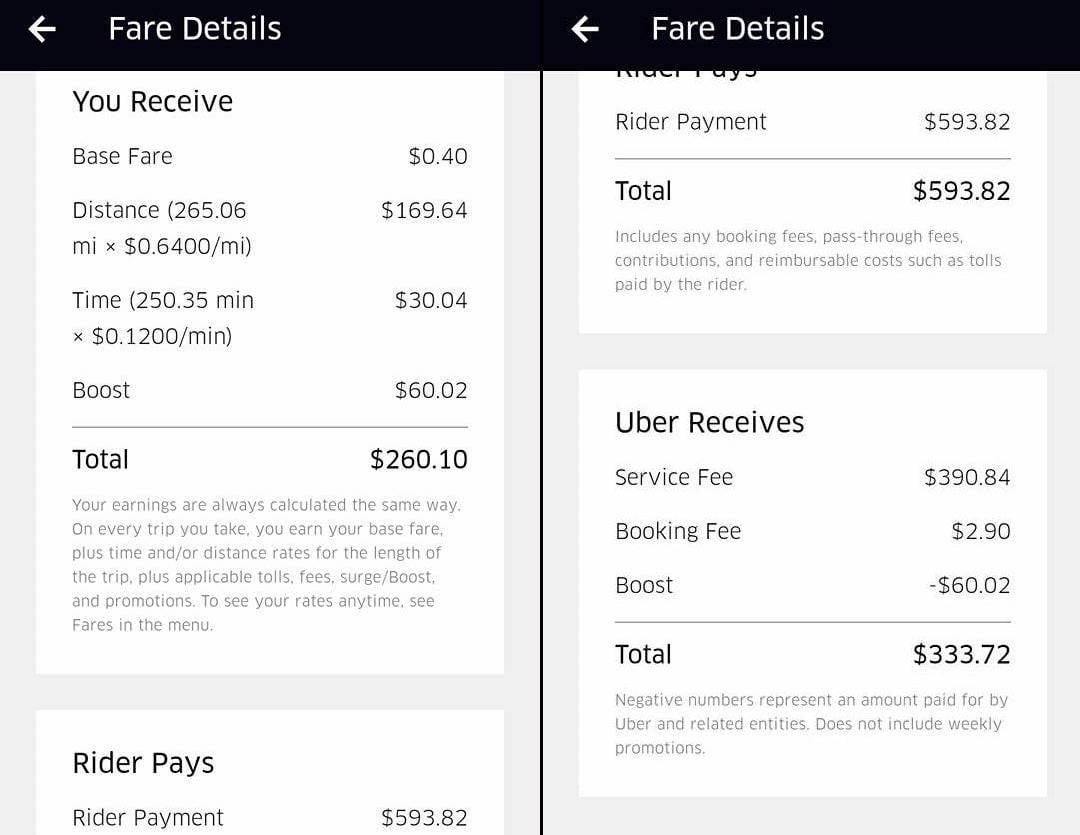

In all, Fleck drove more than 500 miles over nearly nine hours that day. But he only got paid for the first half of the trip, when there was an Uber passenger in his car. Fleck earned $260.10 for the ride. Uber paid him 64 cents a mile and 12 cents a minute, plus a base fare of 40 cents and $60 for a demand-based incentive called “boost.” Depending on how you look at it, he either made about $62 an hour, or just under $30 an hour before gas and other expenses. Uber charged the rider $593.82, of which it kept $333.72, or 56%.

“I believe this negates everything uber has said about us not working for them and us being self-employed,” Fleck wrote in an email to Quartz on Aug. 9, in which he shared the details of his trip. “Because if I am self-employed I just got fucking robbed, because I just made uber a shit ton of money.”

Long trips have always been a gamble for Uber drivers. Kevin Jones hit the jackpot when he drove a woman 550 miles from Omaha to Denver last October. Jones made $702.09 for the seven-and-a-half hour trip, 80% of the total $877.61 fare. Others, like Janis Rogers, do less well. Rogers earned $294.09 in December taking a woman 400 miles from Virginia to New York City. That trip lasted just under eight hours in one direction. There and back, Rogers estimated she made just over $9 an hour after expenses. “This was not lucrative,” Rogers, 64, told the New York Post at the time. “I did it because it was an adventure.”

Uber’s spokesman said long trips like Fleck’s are “exceptionally rare” but that riders “always know the cost of a trip before requesting a ride, and drivers earn consistently for the work they perform with full transparency into what a rider pays and what Uber makes on every trip.” Current guidance on Uber’s website advises riders to “please let drivers know if you’re planning to travel a long distance” and says trips “may automatically end after 4 hours.”

Uber is two months into its first real effort to improve relations with the 1.5 million drivers who underpin its global ride-hailing service, a campaign the company has branded “180 Days of Change.” Volatile, unpredictable earnings—a longtime driver pain point—are high on the agenda. In its first found of changes in June, Uber added tipping, said it would pay drivers after two minutes of wait time, and tightened the cancellation window for riders. The month before the driver campaign officially launched, Uber also debuted new earnings receipts that made it easier for drivers to see what they earned, the rider paid, and the company kept on every trip.

The company has years of ill will to undo with its drivers. Repeated price cuts, misleading earnings claims, longstanding resistance to tipping, courtroom battles over employment status, and exploitative auto-financing arrangements have caused deep resentment and mistrust toward Uber in the driver community. It didn’t help when Travis Kalanick, the company’s founder and recently deposed CEO, was caught on tape berating a driver earlier this year.

Despite Uber’s recent overtures, experiences like Fleck’s show how far the company has to go. Many drivers have been mystified by Uber’s fare calculations ever since the company quietly moved from a commission-based model to a system in which it charges an “upfront” fee to the rider and pays the driver an entirely separate amount based on time and distance. Some feel like the company is systematically underpaying them. Adding tips and tweaking wait times and cancellation fees have done little to address these broader misgivings.