Weekend edition—Trust at the UN, chess on Wall Street, mastiff mania

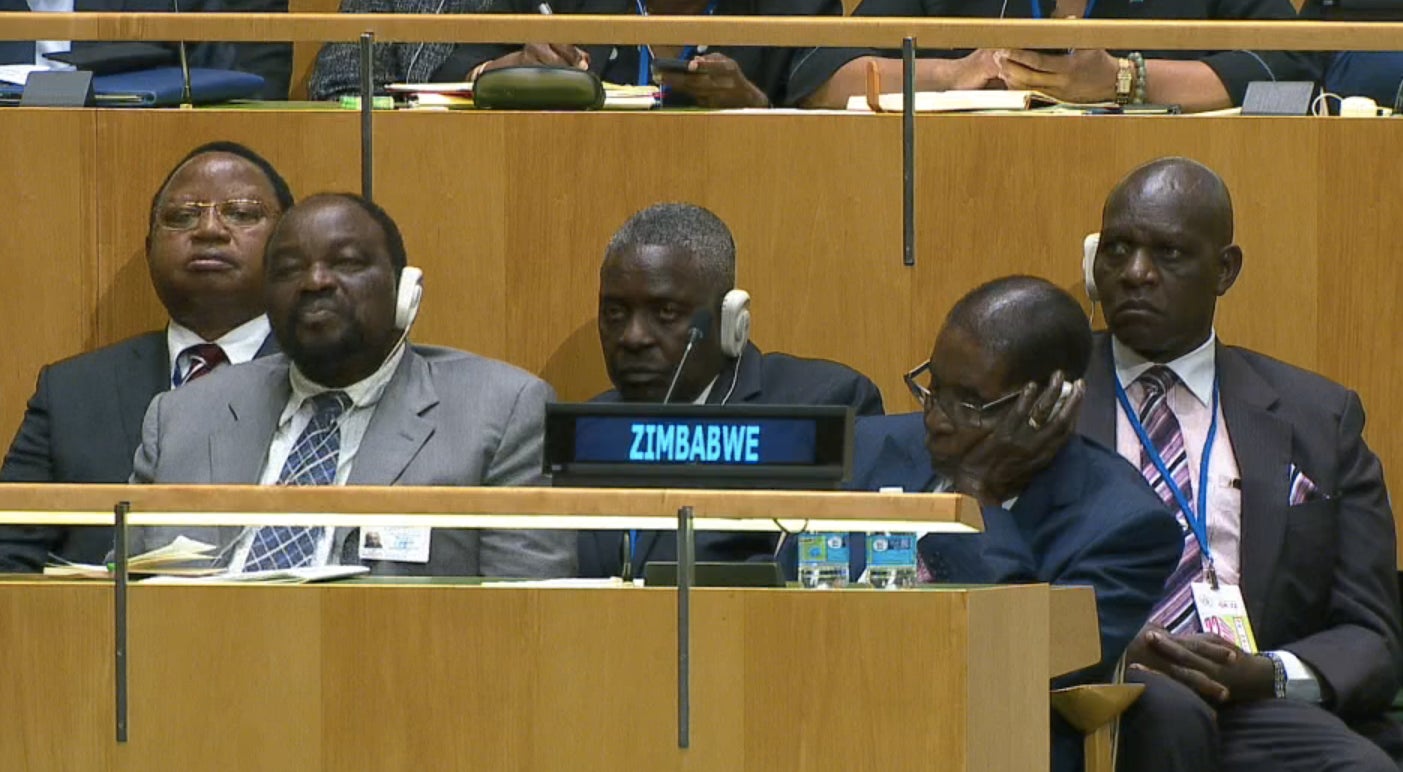

You might laugh at the notion that the UN general assembly has anything to teach the business world. The “world’s biggest meeting” can also, with its fetish for arcane procedures, interminable declarations, and impenetrable jargon, seem like the world’s most dysfunctional one.

You might laugh at the notion that the UN general assembly has anything to teach the business world. The “world’s biggest meeting” can also, with its fetish for arcane procedures, interminable declarations, and impenetrable jargon, seem like the world’s most dysfunctional one.

But what businesses sometimes miss about meetings is that they are not just tools for getting things done. Meetings signal status (who gets to go, who doesn’t). They create shared language and culture. They let people feel heard, so they can then go along with decisions they disagree with. They create shared responsibility—if you were at the meeting, you can’t claim you didn’t know.

Most of all, though, meetings create a commodity no organization can function without: Trust.

It’s a modern paradox that, while we can now transmit megabytes of information in an eyeblink, our brains still absorb it at the glacial baud rate set by evolution. Unless (or until) we invent the neurological equivalent of broadband, you’ll still need other people to do much of the knowing for you, and so you must be able to trust them to get it right.

Trust relies, ironically, on the one type of information our technology doesn’t handle well. It’s the information encoded in smiles, frowns, gestures, postures, verbal tics, facial micro-expressions, even smells—all the friend-or-foe signals our big brains evolved aeons ago to send and receive, often without our even knowing it. Even in video calls, most of that data gets lost in transit.

So that’s what meetings are, above all: not decision-making bodies, but ancient data-transfer protocols for trust creation. And it’s why meetings at the UN, a body created specifically to try to forge trust out of distrust, are so important. Perhaps the way it holds them can even teach a thing or two to anyone who needs to bring warring tribes together. —Gideon Lichfield

Five things on Quartz we especially liked

How scientists write about sex. For a new perspective on the US’s evolving spectrum of sexual norms and shifting gender politics, look at the language scientists use to talk about sex. Katherine Ellen Foley, Youyou Zhou, and Christopher Groskopf teamed up to parse the vocabulary of five decades of scientific literature, and built an interactive tool that lets you investigate the trends yourself.

Who is Angela Merkel? Frequently hailed as the current leader of the free world, German chancellor Angela Merkel is a quietly ruthless politician, with a long list of position reversals behind her. Ahead of Germany’s Sunday election, Jill Petzinger profiles the woman known as “mutti” (mother), with insight into how she’s hung on to power for so long.

The rise and cruel fall of China’s mastiff mania. Ten years ago, Tibetan mastiffs briefly became a prized accessory for wealthy Chinese. When the trend ended, thousands of the huge dogs were abandoned by breeders and owners to roam the Tibetan plateau. Echo Huang offers a disturbing look at what happens when a bubble bursts in the luxury pet business.

Ethics in AI research. Ostensibly to prove the danger of AI in the wrong hands, a Stanford scientist used facial recognition to try to identify people as straight or gay. Dave Gershgorn spoke with sociologists, data scientists, and the embattled researcher himself about the debate over ethics in AI research that resulted instead.

Dispelling dystopian visions of China. A Chinese student at a US university publicly condemned China’s smog and lack of freedom, and was labeled a traitor by peers in China—prompting soul-searching among fellow Chinese expatriates in the West. Siyi Chen explores the tension between admitting China’s problems and defending it against clichés.

Five things elsewhere that made us smarter

Wall Street has a chess guru. Soviet defector and chess grandmaster Lev Alburt has been training Wall Street traders and other powerful individuals in strategy and high-pressure decision-making for 25 years. For Bloomberg Businessweek, James Tarmey spoke to Eliot Spitzer, Carl Icahn, and other students of Alburt about the advantages of a chess-trained brain.

Imagining a more flexible world map. Spain’s Catalonia and Iraqi Kurdistan will call a little more loudly for independence next week, but the US—despite its own revolutionary history—will surely oppose their efforts in favor of the status quo. In the New York Times, Joshua Keating invites readers to envision a world with borders that are a little more plastic.

The crippling cost of college. California Sunday Magazine’s Ashley Powers follows the lives of two students who worked, scrounged, and slept on friends’ couches in order to afford college, to answer the question: Is the degree worth the price?

When a small town in Sweden stopped feeling safe. Once a tranquil Swedish town, Trollhättan’s transformation by economic upheaval and immigration suddenly drew attention in 2015, when a racist attack on a local school left four dead. For Granta, Andrew Brown explores the anxiety and alienation of the town’s emerging neo-Nazi movement.

Robots, sourdough bread, and creativity at work. In Robin Sloan’s latest novel Sourdough, a roboticist is wheedled away from her job by a crock of pseudo-sentient sourdough starter. In a sci-fi twist on the challenges of the modern workplace, it’s only outside the lab and immersed in the sourdough’s world that the hero makes her creative breakthrough.

Our best wishes for a relaxing but thought-filled weekend. Please send any news, comments, puppies, and chess strategies to [email protected]. You can follow us on Twitter here for updates throughout the day, or download our apps for iPhone and Android.