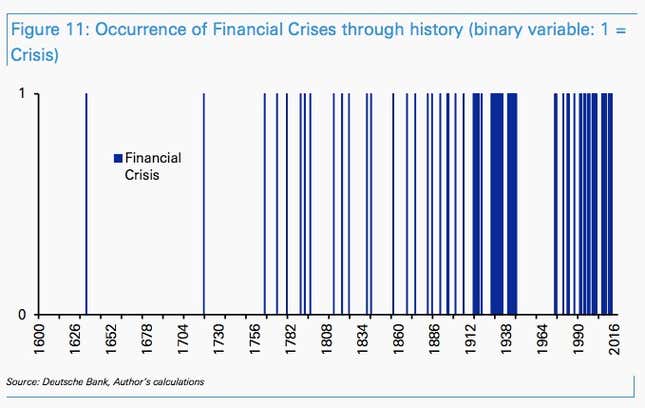

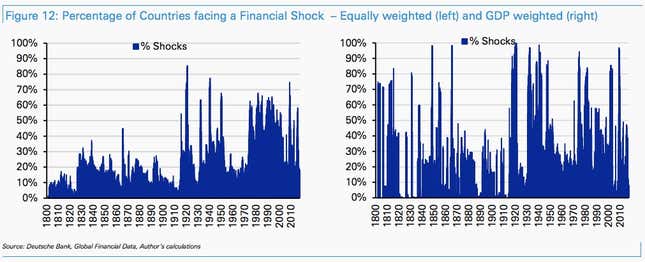

Financial crises are happening more frequently, becoming almost a fixture of modern life, according to research by Deutsche Bank. While meltdowns remain difficult to see in advance, the next panic is almost certainly brewing, and it may well be provoked by the world’s major central banks.

The German bank’s study of developed markets uses this criteria to define a financial crisis: on a year-over-year basis, a 15% drop in stock markets, 10% decline in foreign-exchange, 10% fall in bonds, 10% increase in inflation, or a sovereign default.

Deutsche Bank argues that crises have been increasingly frequent since the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, which, after World War II, fixed exchange-rates and essentially linked them to the price of gold. That coordination ended in the 1970s when the US broke the dollar’s peg to the yellow metal. The link to a finite commodity helped limit the amount of debt that could be created.

As strategists at the Frankfurt-based lender see it, the resulting fiat money system has encouraged rising budget deficits, higher debts, global imbalances, and more unstable markets. At the same time, banking regulations have been loosened. In the US, the industry may soon have fewer restrictions and less oversight, a mere 10 years since the last worldwide crisis.

Post-Bretton Woods, policy makers have the flexibility to create as much money as needed to sooth a financial meltdown. However, this can also provide the foundation for the next one, according to Deutsche Bank. A subsequent, potentially bigger, crisis is more likely because the problem has just been passed along to another part of the financial system. The Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan, and European Central Bank now hold more than $13 trillion of assets on their balance sheets, up from less than $4 trillion in 2007, according to Yardeni Research.

The modern framework can allow credit stockpiles to climb: Global government debt is approaching 70% of gross domestic product, the highest since World War II and up from less than 20% in the 1970s, according to Deutsche Bank. The US has run an annual budget deficit for 53 of the past 60 years.

“We think this leaves the current global economy particularly prone to a cycle of booms, busts, heavy intervention, recovery and the cycle starting again,” Deutsche Bank said. “There is no natural point where a purge of the excesses is forced by a restriction on credit creation.”

Where will the next crisis come from? Deutsche Bank says there are plenty of things to worry about. Italy has a massive debt burden, a brittle banking system, and a dysfunctional government. China may have a property bubble on its hands and has long been fueling its growth with debt. Populist political parties could disrupt the world order as we’ve known it.

But one of the most obvious problems is how to unwind central bank balance sheets of unprecedented size, during a time of record-high peacetime government debt, while bond yields are at multi-century low interest-rates. The bank’s strategists say they’re “quite confident” there will soon be another financial shock, a pattern that will be repeated until the world figures out a more stable financial framework.