On Halloween weekend in 1948, two dozen people in a small American town suddenly died. The killer came in on the air—or rather, it was the air.

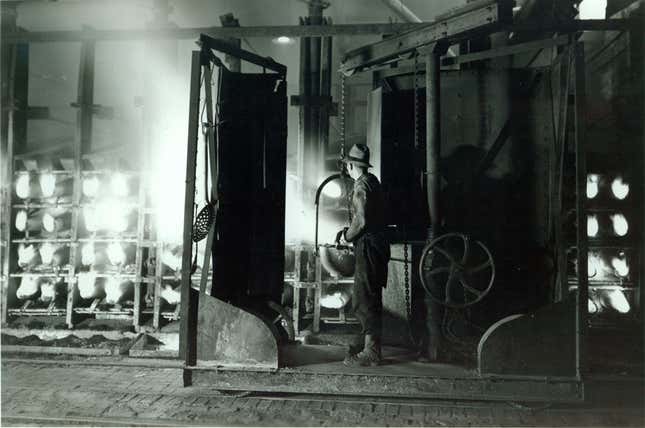

The week prior began like any other; the 14,000 residents of Donora, Pennsylvania woke up to hazy skies, but they were used to that. It was two decades before the passage of the Clean Air Act, which would become one of the most influential environmental laws in the country, and for years, the town had been riding high on the economic boom of the steel plant and zinc works in their town (zinc is used to galvanize steel). US Steel operated the zinc plant 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The once-grassy hillside nearest the plant was completely denuded.

“While the zinc works was in operation there was no vegetation at all on these hillsides. The air would kill all the vegetation,” said Charles Stacey, a Donora native who was a senior in high school that year, gesturing towards the landscape where the zinc works used to be. It was a dreary day in early October 2017, and a light drizzle on the desolate scene added to feeling that we were staring at a site of tragedy. The white shells of zinc works buildings are all that stand there now.

Back in the 1940s, the area by the zinc works was sometimes suffused with a cloud of bright yellow. The days in Donora typically began in a hazy fog; by afternoon winds would sweep through Donora’s little valley and clear the air.

No one thought anything of it. The impacts of industrial pollution on human health were not yet widely known among the general public. Plus, says Stacey, “You didn’t step on US Steel’s toes, because your dad had to go to work there.”

But the week before Halloween (which fell on a Sunday that year), the morning haze came and never left. The little town, built in the basin of the Monongahela River valley, began to fill up. By Wednesday, the air was thick and visibility was low. “You put your hand out and couldn’t see the tips of your fingers,” Stacey remembers. Plants began to die, then pets. By Saturday, it was people.

Local fire crews raced door to door administering oxygen to people who struggled to breathe, but no one knew what was killing them.

At the time, there were no laws in the US limiting the amount of toxins a company could release into the air. Companies regulated themselves—which is to say, they didn’t. The same was true for England; a few years after Donora, in 1952, a poisonous smog in pollution-choked London killed some 12,000.

A federal investigation of the Donora incident later found that a weather “inversion,” a phenomena where warmer air floats above cooler air, formed a “cap” that kept the air stagnant and prevented pollution from exiting the area.

On Sunday—Halloween—it rained, dragging the pollution particles to the ground and clearing the air. By then, 26 people had died; they were mostly elderly, with poor lung capacity. They’d inhaled sulfuric acid, nitrogen dioxide, fluorine, and other poisonous gases that restricted the capillaries in their lungs and triggered inflammation, ultimately suffocating them.

The US Steel Corporation would later call it an “act of God.” The company, which still operates steel works in the US, has never formally acknowledged its role in the disaster, according to David Lonich, a historian at the the Donora Historical Society—better known as the “Donora Smog Museum,” a storefront in downtown Donora, full of newspaper clippings and photos from the time of the disaster.

More than 100 Donora residents later sued US Steel, and the company settled for $256,000 out of court. This year, residents again sued the company, claiming the pollution US Steel left behind continues to make them sick.

The town is now a dreary post-industrial hamlet. The steel and zinc works are gone, and the population is dwindling. “It’s turning into a ghost town. We don’t have a bank, or a grocery store, or a bar,” Lonich says.

But Donora is Patient Zero in the long story of American environmental regulation. The Donora “killer smog” introduced the word “smog” into the US lexicon—and the idea that it could kill you, or shorten your life by making you ill, which is now a basic scientific fact.

Roughly 20 years later, the US’s first (and only) omnibus air pollution legislation became law, and in 1998, on the 50th anniversary of the disaster, an Environmental Protection Agency employee named Marcia Spink gave a speech describing “the debt of gratitude that the people of the United States owe Donora and the event that led to the federal Clean Air Act of 1970.”

“It is definitely tied to the ability of this country to wake up and realize that air pollution isn’t just a nuisance but something that makes things so dirty that it can kill people,” she said.