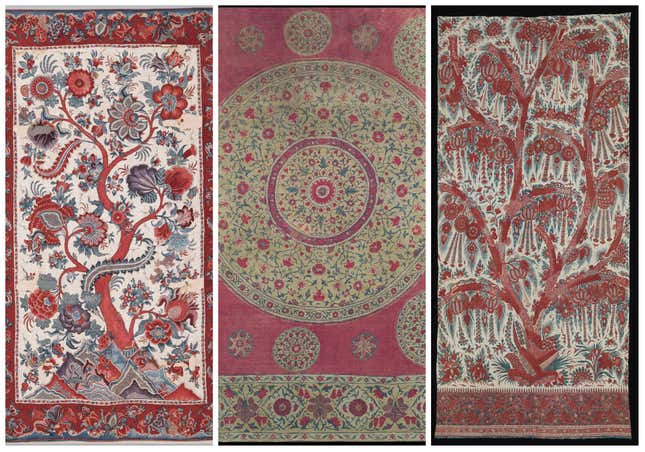

For many centuries, Asia was both the center of the world’s textile production and the source of its fashion trends. India, in particular, was responsible for the largest share of textile production and for much of the finest kinds of cloth. Indian manufacturers had sophisticated methods for weaving cotton into light, breathable textiles, and vibrant, long-lasting dyes that gave these fabrics dazzling colors. From the Middle Ages to the early 19th century, Indian textiles were one of the most popular global commodities. Indian producers developed special lines for export to Southeast Asia, Africa, and Europe, adapting to local demand.

Today, the centers of the global fashion industry lie in Europe and North America, with cities like New York, London, and Milan setting trends for the rest of the world. It’s still in Asia, however, that the textiles designed in these fashion hubs are actually made, with China and India leading global production. This unequal separation of design and manufacture is rather new in history. The story of how this came to be reveals the extent to which Asia’s textiles and fashion sense inspired the modern fashion industry. It also shows how the West’s appropriation of those aesthetics paved the way for the troubling fast-fashion environment we live in today.

Europeans began sailing to India in the late 15th century in search of spices, but textiles soon became the most important import from the region. By the 17th century, such large quantities of Indian cloth were flooding into cities like Amsterdam, Paris, and London that leaders of local textile industries grew afraid. They lobbied governments to ban Indian textiles. The French monarchy responded, not only forbidding merchants to import dyed cotton cloth from India, but also forbidding manufacturers to make dyed cotton cloth themselves. Lawmakers reasoned that French versions of Indian cloth would be only poor imitations of the real thing, and so would encourage more demand for the genuine Indian article.

But French consumers, as historians like Felicia Gottmann of the University of Dundee have shown, were willing to break the law to get their hands on the Indian cloth that they craved. While the ban was in force, from 1686 to 1759, tens of thousands of pieces of Indian cloth were smuggled into France. As they purchased these illicit goods on the black market, French consumers, particularly upper-class fashionable women, risked fines as large as the cost of a house, confiscation of their property, and the indignity of appearing in court alongside people they considered their social inferiors. They transformed the illicit cloth into nightgowns, coverings for furniture, and, for those willing to defy the law in public, street clothes. Punishments fell most heavily on smugglers and merchants, but it was not uncommon to see women dragged off the street or out of their own homes for possession of Indian cloth. In 18th century France, the state took crimes of fashion seriously.

By the 1750s, government officials and their economic advisors were ready to abandon these heavy-handed and ineffective measures. They decided on a new policy: the French government would allow Indian textiles to flow into the country, and allow French manufacturers to imitate them. In order to protect domestic industry from the influx of superior Indian goods, the monarchy began a program of what might be called industrial espionage, sending agents to India to learn how manufacturers there made such excellent cloth. Soon, dozens of French firms were imitating Indian designs, creating a large domestic industry of Indian-style cotton cloth.

French efforts had some initial success, but even with government help, local manufacturers couldn’t quite match the fine weaving, vibrant dyes, and reasonable cost of the best Indian wares. One manufacturer, Cristophe-Philippe Oberkampf, realized that if his products couldn’t compete with Indian goods in quality, durability, or price, then he would have to try something different. Beginning in the 1770s, he transformed the production of his cotton textiles using new methods of large-scale factory production and new machines for printing images onto cloth. He also collaborated with government officials and high-profile scientists in the search for new synthetic dyes that would match the bright colors used in India. His modern textile plant at Jouy-en-Josas, a small town outside of Paris, became a key site in Europe’s emerging Industrial Revolution.

Even more important than Oberkampf’s factory system or scientific advances, however, was his decision to work with the popular French painter Jean-Baptiste Huet to create affordable fashion. When Oberkampf opened his textile business, he had focused on making high-quality imitations of Indian textiles that were good enough to be mistaken for the real thing. While today his products might be condemned as counterfeits or cultural appropriation, happy customers wrote to him saying that their new ‘Indian’ dress had everyone fooled! In the 1770s, however, Oberkampf adopted a new strategy, printing Huet’s distinctly French designs on cheaper cloth.

While Indian textiles were celebrated for their durability, with bright colors that stayed vivid even after repeated washing, Oberkampf was now making cloth that wasn’t meant to last. He invented modern fashion marketing, releasing designs in short runs, and changing them every season. While Indian cloth had been a long-term investment, Oberkampf was creating the idea of clothing as temporary trend.

For the first time, middle-class shoppers were encouraged to think of buying clothes not as a long-term investment, but as an ephemeral experience of chic. The modern fashion system, with ‘seasons’ of changing trends conceived in a Western design studio, was born as France’s answer to Indian cloth.

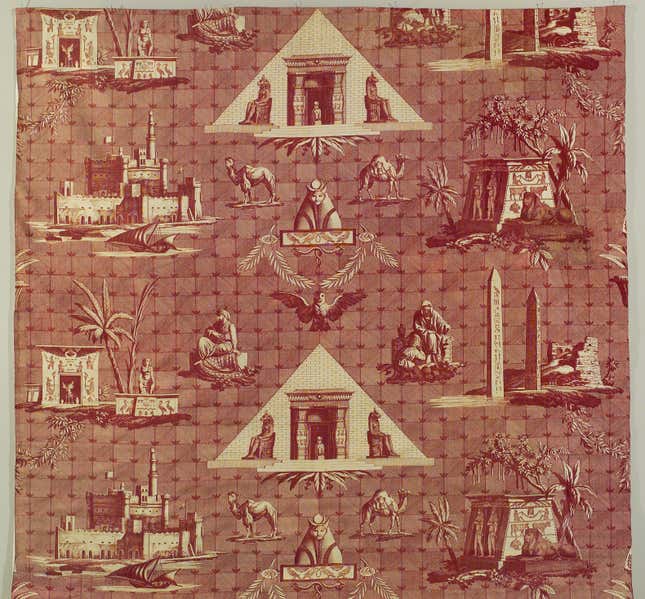

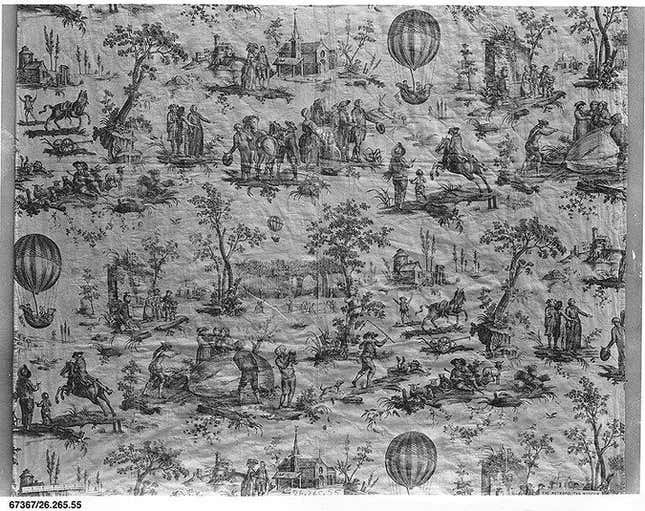

Huet provided Oberkampf with topical designs that referenced political events, scenes from recent novels, or the latest cultural phenomena. One of the most popular designs for Oberkampf’s toile de Jouy (named after the town of Jouy-en-Josas) commemorated the first hot-air balloon flight in 1783, while others exploited the fascination with Egypt after Napoleon’s invasion of the country in 1798. Textiles printed with such designs were made to become obsolete; no one wanted to be caught wearing a dress made of old news. Oberkampf’s marketing strategy, taken to its logical conclusion, fuels the success of “fast fashion” companies like Zara or H&M, which offer access to affordable, trendy clothes that aren’t made to stay around.

As he began to convince consumers that following ephemeral trends was more exciting than consuming exotic (and higher-quality) Indian cloth, Oberkampf made an enormous fortune, becoming one of France’s most prominent businessmen. The trendy Oberkampf neighborhood in Paris, a textile museum in Jouy-en-Josas, and a continuing vogue for his toile de Jouy all testify to Oberkampf’s legacy. While he never matched his Indian competition in terms of quality of dyeing and weaving, he did cement France’s place in the global textile industry, as all of Europe developed a craving for his designs. As the inventor of fast fashion, Oberkampf paved the way for future entrepreneurs to exploit the fashion cycle, creating inexpensive short-lived, trendy garments made to go out of style.

Oberkampf’s 18th-century answer to Indian cloth remains a staple of the trend-oriented global fashion industry he helped created. But as India returns to the center of fashion, with new ‘Made In India‘ campaigns and a vibrant design scene, it may not be so easy for European centers to dictate what the trends of the future will be.