The time has nearly come for Mexico’s president, Enrique Peña Nieto, to unveil his plan to reform Mexico’s heavily protected energy sector. But is Mexico ready?

Peña Nieto is slated to propose a sweeping energy reform this week, which could come as early as tomorrow (August 7), and include provisions to open Mexico’s state-held oil industry to private and foreign investment. Many believe that the imminent reform is necessary if Mexico wants to keep its energy sector afloat, but any discussion of Pemex, Mexico’s state-run oil monopoly, is a sensitive one.

Mexico is currently the world’s ninth largest producer of oil, and is still believed to hold some 14 billion barrels of reserves. But since 1938, when president Lázaro Cárdenas privatized the oil industry in a backlash against foreign influence, state stewardship of the industry has been a matter of intense national pride. For many decades, this proved to be a great thing. Pemex poured billions into the nation’s schools, hospitals, highways and more, and has effectively helped build much of modern-day Mexico. Schoolchildren are taught about Cárdenas’s “heroic decision.”

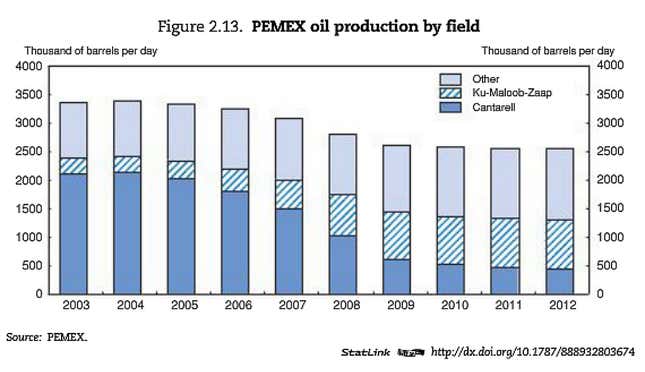

But the reality is that Pemex has become dangerously inefficient. Oil production has fallen every year since 2009, and hit an eight-year low last year. The country now produces roughly 2.6 million barrels a day, down from a high of 3.5 million in 2004. At the current rate, and without private and foreign investment, Mexico could become a net energy importer by 2020 for the first time in nearly a century. (The following graphs are from the OECD’s recent economic survey of Mexico—pdf.)

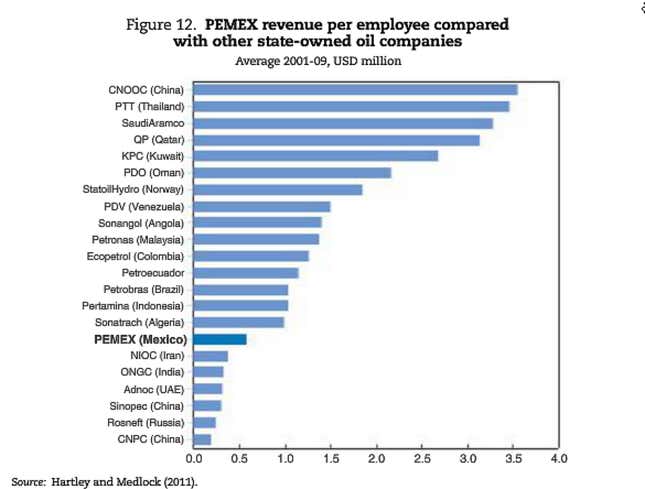

The company’s revenue per employee tells part of the tale:

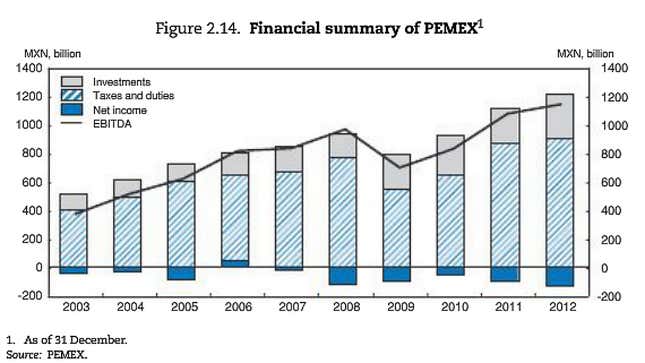

And Pemex hasn’t even returned a profit in over seven years, which is a serious problem considering that it provides the government with nearly 40% of its budget:

Cantarell, Pemex’s largest oil field, which is located offshore in the Bay of Campeche (the southern part of the Gulf of Mexico), tells another part of the story. When Cantarell was discovered back in 1976, it was one of the world’s largest oil fields. But production peaked in the mid-2000s and has declined rapidly ever since. Mexico’s early success in finding shallow-water and inland oil has led to a crippling complacence about pursuing new ways to mine for oil. One Pemex executive went as far as saying that Mexico is now some 30 years behind the industry standard in deep-water exploration.

That’s why Peña Nieto’s government, along with many others, contends that opening up the country’s oil market is vital. Deep water and shale-rock formations are believed to hold some 50% of the country’s oil reserves, but without foreign technical expertise, Mexico will be hard-pressed to pump out much of it, if any.

Serious obstacles, however, stand in the way

Currently, according to the Mexican constitution, Pemex has exclusive rights to explore, exploit, refine and process crude oil and natural gas; produce basic petrochemicals and liquid petroleum gas; and carry out first-hand sales of such hydrocarbon products. And amending the constitution is a sensitive matter. Roughly 65% of Mexicans are opposed to opening up the oil industry.

For many, Pemex’s problems lie in its stiff tax burdens, not its lack of innovation. Pemex currently pays 70% of its revenues to the government, which limits its ability to fund improvements and exploration. For others, Pemex’s woes are a result of corruption, mismanagement, and a broken corporate structure that means it keeps hundreds of unnecessary employees on the books.

Then there are questions about just how open Mexico’s oil industry should be. If private investors are let in, how will revenue sharing work? Will private and foreign companies be allowed to not only help Pemex explore and extract, but do it on their own too?

Some of the skepticism likely comes from the backlash felt from previous privatizations. Carlos Slim, who bought Mexico’s once state-owned telecom company, Telmex, spent four years as the world’s richest man according to Forbes, but according to a study performed last year, Mexicans are still being overcharged billions of dollars per year for phone and internet service. Mexicans are also anxious about relinquishing state control of their natural resources. But when your government is counting on a sinking ship to keep it afloat, what choice is there?