It’s a financial lesson in being careful what you wish for.

Brazil’s finance minister Guido Mantega declared the existence of a “currency war” in 2010, as wealthy countries used stimulus money to lower interest rates and escape the global recession, sending yield-seeking investors to emerging markets like Brazil. These capital flows pushed up the Brazilian real, making the country’s export-driven economy less competitive.

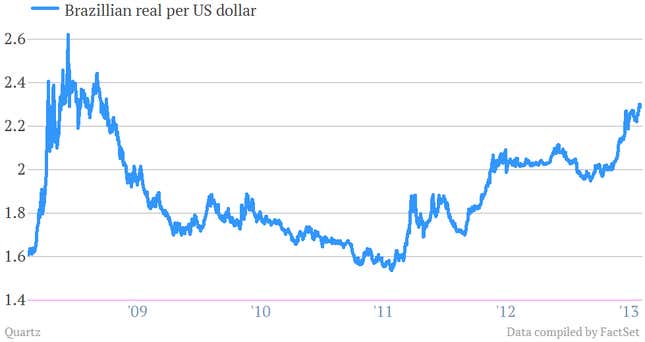

The “currency war” story was always over-rated; global demand was ultimately more important, and emerging markets exporters found various ways to protect their currencies. In February, Mantega said his country had “neutralized” the currency war, stabilizing its currency at roughly 2 reals per dollar. With the US Federal Reserve signaling a willingness to slow the bond-buying program that offended Mantega so much, you might imagine he’s taking a small victory lap.

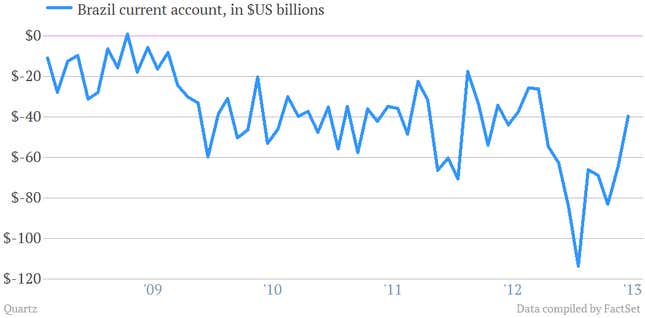

But unfortunately he has a new set of problems to deal with, like Brazil’s balance of payments:

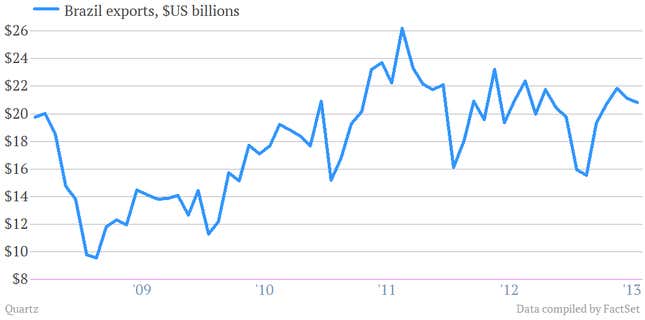

This summer, Brazil imported a lot more than it exported, and now it’s facing a record deficit in its current account balance, totaling 3.2% of GDP on the year. It’s not quite bad enough to be called a crisis, especially with the country’s significant foreign exchange reserves, but it’s an ominous sign, caused in large part by declines in global commodities prices that have hurt the country’s exports:

The magic of a free-floating currency is that it adjusts to respond to phenomena like this, and sure enough, the real is now at its weakest level since the financial crisis, which should make its goods more competitive on the global market:

There’s a catch: That depreciation is worsening Brazil’s already problematic inflation (6.27% on the year) because the country’s still-developing economy relies on imports for many goods it can’t make itself. If the real keeps weakening, Brazil’s central bank will feel pressure to keep raising interest rates above the current 8.5%, which could choke off Brazil’s anemic growth.

It would be nice, then, if Brazil’s central bank got some help on the inflation front from foreign investors, whose search for yield in Brazil could cause the currency to appreciate again. That’s why Mantega cut the tax on foreign investment to zero at the beginning of the summer. That may not be enough to attract investors, given Brazil’s weak prospects for growth and the steady drumbeat of US monetary tightening, which has already knocked the carry trade out of whack.

But if Brazil winds up caught between inflation and stagnation at year’s end, Mantega might look back upon the currency war era as the good old days.