A campus can reveal a lot about a company’s culture. Google is famous for its outlandish office spaces, which contain egg pods and caverns, capturing its founders’ quirky personalities. Amazon is known for its door desks, symbols of founder Jeff Bezos’ frugality (even though they were more expensive than actual desks).

If there’s one Chinese company that can rival those foreign ones in visibility worldwide, it’s the e-commerce giant Alibaba, one of the world’s most highly-valued companies. Founder Jack Ma regularly appears at overseas events, where he captivates audiences with stories about his pre-Alibaba days when his resume was so weak he couldn’t even get a job at KFC. The company’s Singles Day shopping event is well-known enough worldwide to get American celebrities to come promote it. Every now and then Ma breaks into dance at a company event.

Like Amazon, its US-based counterpart, it’s moving beyond online commerce and into offline retail, cloud computing, and consumer finance. It’s also expanding internationally, opening up R&D centers in Singapore, Israel, and the US.

Very little of Ma’s flamboyance and ambition comes across at Alibaba’s headquarters in Hangzhou’s Xixi district (about 180 km from Shanghai). At first glance, it looks like an ordinary office park. If anything stands out in particular, it’s the presence of two contrasting motifs in the central courtyard—the influence of classic Chinese literary and art forms, and a towering series of human sculptures.

Visually, the aesthetics of the two themes don’t appear to match. But they each capture a specific part of how Alibaba sees itself, and the challenges that lie ahead for the company.

Band of outsiders

Markings of imperial China dot the 260,000 square meter campus. Conference rooms have names like “Green Branch Peak” and “Banana Plains,” references to the Qing dynasty novel Dream of the Red Chamber (the 18th century work is considered one of China’s greatest literary achievements and has been compared to Gone with the Wind and War and Peace). The center of campus contains a walled garden inspired by the Jiangnan style of local architecture associated with Zhejiang province and other areas in eastern China along the Yangtze river. A walled portion of it is open only to Jack Ma—his office is there—and other top executives, who use it as a meeting spot for guests such as Justin Trudeau, who visited in late 2016.

Chinese martial arts in particular is a common motif on Alibaba’s campus. Cartoon depictions of warriors are spread throughout hallways, meeting spaces, and even the parking lot.

Jack Ma’s fondness for martial arts stems in part from his admiration of the work of Jin Yong, a Hong Kong-based writer who published a series of adventure novels revolving around heroes and combat scenes. While published during the 20th century, the books are usually set in medieval Chinese history and draw on a long tradition of China’s wuxia, or martial arts-related fiction. He’s incorporated much of the literature into Alibaba’s internal culture.

The company’s values, for example, are dubbed the “Six Vein Spirit Sword,” which Ma borrowed from Jin Yong’s novel Demi-Gods and Semi-Devils, whose characters are inspired by Buddhist philosophy. At Alibaba, each “vein” of the sword (which is not an actual sword in the novel) represents a company value—customer first, teamwork, embrace change, integrity, passion and, commitment. Employees are rated on their performance in part based on how well they fulfill each of these values.

All employees at Alibaba choose a nickname for themselves. Originally, Alibaba staff drew from characters in Jin Yong’s martial arts novels. Jack Ma’s nickname, for example, is Feng Qingyang, named after an elderly swordsman from the Jin Yong book The Smiling, Proud Wanderer. Nowadays, staff can take their nicknames from other inspiring characters too—Marvel superheroes and Korean dramas are popular, one employee told Quartz. These are used in all professional contexts—emails, group meetings, even performance reviews.

Brian Wong, Alibaba’s vice president of global initiatives and an employee since 1999, says Alibaba uses the nicknames, and the broader martial arts motif, to inspire staff to think of themselves as outsiders fighting for a cause.

Much of Alibaba’s past and present has hinged on it taking on established, powerful rivals. In the previous decade, while competing hard against eBay in China, the company steadfastly refused to charge vendors fees to list on its site. Investors quivered, but Chinese merchants embraced the policy, helping Alibaba to drive one of Silicon Valley’s largest companies out of the country. Nowadays, with its Ant Financial finance affiliate, the company is taking on a larger rival—state-owned Chinese banks, which Ma argues don’t adequately serve the Chinese consumer.

Jin Yong’s characters, Wong says, are like “a brotherhood, like a band of brothers, it’s a group of people that are fighting for values of righteousness, loyalty.”

“Often times they are sort of a peripheral group, they are not the mainstream. They have been shaped by things in their life they think are not fair or not right,” he adds.

Humble touches

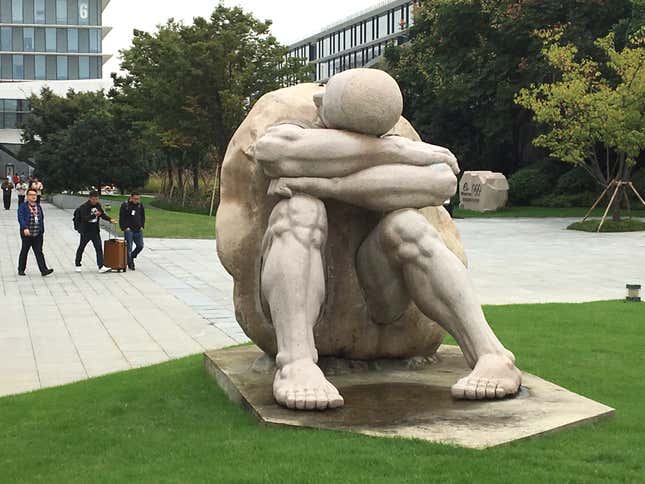

Alibaba’s courtyard also contains a series of sculptures that the company commissioned from contemporary Chinese artist Wang Wei. They depict giant, stern human figures in states of distress.

These statues represent another facet of Alibaba’s campus and corporate culture—humility.

Despite being valued at nearly $450 billion, Alibaba’s offices aren’t lavish. A typical office floor consists of a series of desks and some ordinary cubicles. For amenities, there are massage chairs, and the odd foosball or ping pong table.

Wong says the lack of glamor at one of the world’s most highly valued companies helps preserve a culture of modesty among staff. Even at its size, the company faces stiff competition from e-commerce rival JD.com, as well as social media giant Tencent, which has made inroads in online shopping with its popular WeChat messaging app. With over 50,000 employees, the company has to ensure staff doesn’t become complacent.

“One thing we’ve talked a lot about now at Alibaba is maintaining a sense of humility. The company has lots of influence on the economy and business in China, and extending into the world. But that’s a privilege and a responsibility,” Wong says. “If you start to give all the employees all these things that make them feel entitled, then they’re going to treat customers in a way that’s much different.”

City and state

Alibaba’s Xixi campus is just one of several it has in China. A smaller campus in Binjiang, 40 minutes by car from the Xixi headquarters, holds offices for employees that work for Alibaba.com, the company’s business-to-business e-commerce site, as well as AliExpress, its global-facing e-commerce site. Cainiao, Alibaba’s logistics arm, and Ant Financial each have separate offices in Hangzhou.

Alibaba has transformed the city. It was once primarily a destination for tourists heading to West Lake, a UNESCO heritage site. Now it’s a startup hub that vies with Shenzhen and Beijing for influence in China’s tech industry. Many Alibaba alumni have founded large companies that are based in the city, including Mobujie, a fashion social network valued at over $1 billion (paywall), and Beibei, a shopping site for mothers (paywall).

Like many Chinese tech giants, Alibaba’s relationship with the government is close but complicated. Ma’s philosophy is to be “in love with the government [but] don’t marry them.” Recently though, as the company has grown more influential, the government has increasingly relied on it for its own purposes. Last year Alibaba company partnered with the Hangzhou government to monitor traffic data across the city. It also is working with the city’s housing bureau to develop an online marketplace for house rentals, powered by Ant Financial’s controversial social credit scoring system. There’s even a spot on Alibaba’s Xixi campus that serves as a “designated meeting space where law-enforcement staff visit occasionally” to help with “established criminal cases,” a representative told the Wall Street Journal (paywall).

Scale and chaos

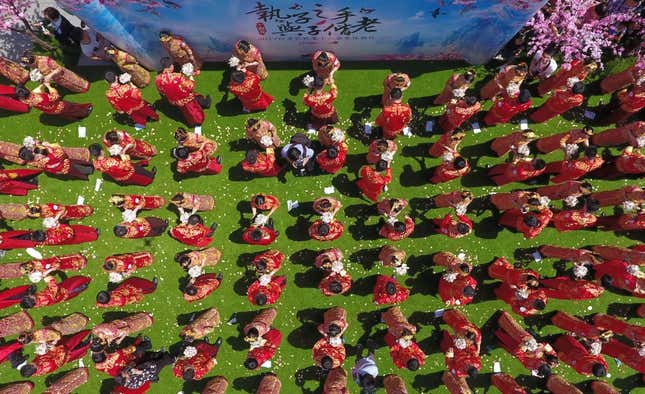

There are a few times each year when the sheer scale of Alibaba comes to life, sometimes chaotically. One is Alibaba Day, which takes place every May 10. Employees’ families are invited to campus to partake in various activities, including a “wedding” for newlywed couples, often officiated by Jack Ma himself. Wong says that the weddings are a symbol of valuing employees as family—at times, literally. Back in 2003, during China’s SARS epidemics, employees ran the business from their homes, often enlisting their parents or grandparents for help. The weddings, Wong says, are “the company’s way of saying thank you to the families.”

Later in the year, as the company prepares for its annual Singles Day shopping bonanza in November, the campus fills with signs and posters promoting the event, and eventually, tents for employees working long hours.

Wong, a Palo Alto, Calif. native, says that Alibaba’s campus might seem modest by the standards of Silicon Valley, where Apple recently unveiled its spaceship-like new digs. “If you’re comparing it to Google or Facebook, you’re not going to think this is impressive. But if you’re comparing it to other Chinese companies, it’s a pretty darn good campus,” he says.

Ultimately, like its more elaborate counterparts in other parts of the world, he says, it’s designed to inspire employees in its own way: “This is a similar approach, but with Chinese characteristics.”