An avalanche of sexual harassment claims swept through Silicon Valley in 2017. It claimed some of the most recognizable names in startups and venture capital. Chris Sacca, Robert Scoble, Dave McClure, Steve Jurvetson are all out of a job (or fund). It started with Uber almost a year ago and, by summer, top executives and engineers had been forced out at Amazon, 500 Startups, Sherpa Capital, Greylock, and at last one venture fund was effectively shuttered.

Already, some of those forced out of power have begun trying to regain a measure of public redemption. Most controversially, perhaps, is Justin Caldbeck, 41, founder of Binary Capital. Six women had accused (paywall) Caldbeck of unwanted and inappropriate advances in business discussions, according to The Information, and, after lashing out at the accusers, Caldbeck announced his departure from the venture firm.

Who’s Out in Tech:

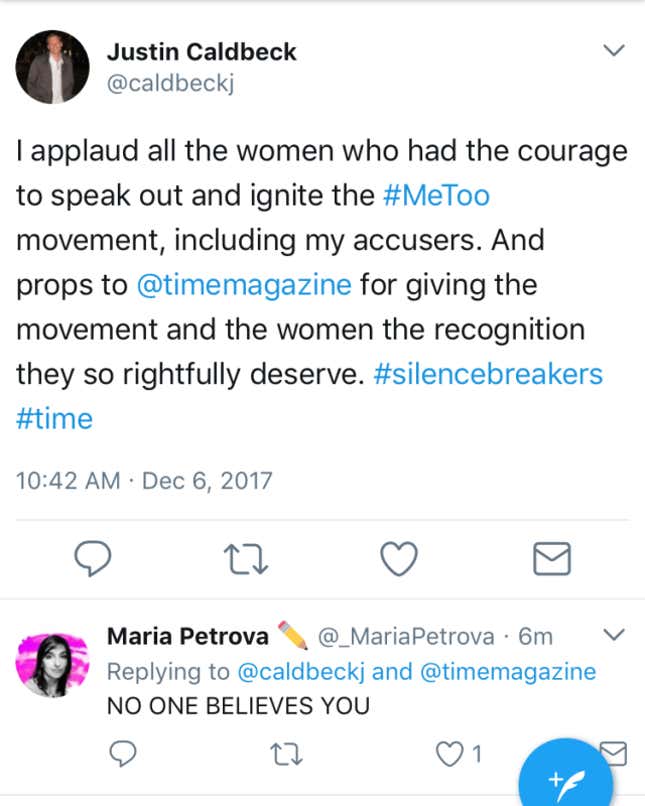

Caldbeck’s public efforts at redemption, however, have not gone well. In November, he addressed 50 students at Duke University, his alma mater, on the dangers of “bro culture.” Then, in December, Caldbeck took to Twitter to praise Time magazine’s choice for Person of The Year: “silence breakers,” women who have spoken out about sexual misconduct. “I applaud all the women who had the courage to speak out and ignite the #MeToo movement, including my accusers,” he wrote in a post, later deleted. Many pointed out that Caldbeck’s statements strained credulity and, worse, did more harm than good for women.

Such attempts at redemption have sparked a debate over whether abusive investors and executives removed from positions of power should ever regain a prominent place in the technology community. Some argue they shouldn’t be faulted for seeking a second chance, if the effort is sincere. One can see the foundations being laid for such a come-back in the litany of blogposts this year by investors accused of harassment with titles such as “ I’m a creep – I’m sorry” (McClure) and “I have more work to do” (Saaca).

This sort of public acknowledgement ignores the true victims, says Joanne Wilson, a New York angel investor. People who permanently derail women’s careers, and inflict psychological damage on victims, should not expect to get a second chance, let alone be praised for their mea culpas. “Let’s talk about what they have left in the dust and let them see what it feels like to be stymied in their career and feel uncomfortable,” she writes by email. “I’d suggest they all take off some serious time and remove themselves from the industry perhaps never to return but they should have thought about that long before they used their power inappropriately.”

Sarah Lacy, technology journalist and founder of the news site Pando, argues that perpetrators should be making room for those who haven’t abused their power, not try to recast themselves as a champions for women in Silicon Valley. “[Caldbeck’s] actions just show he doesn’t even have a clue of what he’s done and why it’s damaging,” Lacy tells Quartz. “It’s so nakedly all about him.” Callback apologized to his victims with emails and handwritten notes, some with identical wording. “It’s such a shocking peek inside his psyche,” she says “Everyone wants him to go away, and he won’t…The least you can do when you systematically victimize people is not to make them have to keep looking at you and interacting with you.

What women need, Lacy says are more women in venture capital and startups as well as a ban on investors with a history of abusing women. “There is no birthright to be a VC,” she says. “It’s a lottery ticket job.”

Caldbeck declined to speak on the record for this article. But he isn’t alone in seeking redemption, some for serious crimes.

Tech executive Gurbaksh Chahal, too, has been making the rounds. Chahal pleaded guilty in 2013 to two misdemeanors after being caught on video hitting and kicking his girlfriend 117 times in 2013, and violated probation a year later by attacking another girlfriend. In October, the disgraced executive spoke at a Las Vegas cryptocurrency conference. The conference founder defended the decision on Twitter: “I do not support domestic violence,” he wrote. “I also don’t believe in lifetime bans on a businessman speaking about his business.”

Pishevar has come out swinging after a fusillade of accusations. Five women told Bloomberg that they were sexually assaulted or harassed by Pishevar, and a rape allegation was leveled against him in the UK. Pishevar called it a “smear campaign” after relinquishing his positions at Sherpa Capital and Virgin Hyperloop One.

In the past, any bright line Silicon Valley has drawn over sexual harassment has tended to fade over time. Lacy believes anyone who stands credibly accused of sexual harassment today could be back in Silicon Valley’s good graces soon enough. “There are endless second chances in this industry,” she says. “In the next ten years, they will probably have an entré into the industry, whether they deserve it or not.”

But things are changing. As I wrote earlier this year, for perhaps the first time, men in Silicon Valley are paying a price—in dollars, jobs and prestige —for bad behavior including everything from groping to verbal disparagement. Sexual harassment claims now take days, not months, to elicit a response. Investors have begun actively steering away founders from venture funds with questionable histories of treatment of women. Venture capitalists are now responsible for their partners’ predatory behavior in a way they were not before (see Binary Capital), and limited partners are now vetting the conduct (paywall) of the venture funds they back.

Public commitments are shifting norms too. In June, LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman called on venture capitalists to sign on to a “Decency Pledge,” and Microsoft announced (paywall) in December that it will end the use of forced arbitration for sexual harassment cases and support a federal law making them illegal.

Despite this, the co-founder of venture firm AlphaPrime Claudia Iannazzo says that Silicon Valley culture will ultimately change when women near parity with men. “Culture only truly shifts once more women are in power,” she told Quartz last year (she also runs Parity Partners, which helps venture firms find qualified female job candidates). “It’s not the vocabulary of the industry that’s the problem. It’s the gender of the industry.”

Today, only about 6% of senior venture capitalists are female (down from 10% since 1999) and just 2.7% of venture-backed startups have female CEOs, according to studies by Babson College and Columbia University. At least half of female founders personally report enduring sexual harassment, according to a 2017 survey of 869 founders by the investment firm First Round.

Yet women still see this as a far bigger problem than men. Seventy percent female founders says sexual harassment is underreported, reports First Round, while only 35% of male founders agree (a federal analysis of sexual harrasment cases found 70% percent of people who experience harassment never report it to a supervisor or manager). Men were also four times more likely than women to say the media’s coverage of the issue was “overblown” (22% vs. 5%).

Wilson, who regularly invests in startups with female founders, warns that turning a blind-eye to the #MeToo moment today may come back haunt those who ignore it. “At some point, the women who have risen to the top…will all stand up and dominate this industry,” she writes. “All of these bad players will never work in the tech industry again because nobody will tolerate it.”