It’s official: “Shitpost” is the word that best describes the internet in 2017

Each January, the American Dialect Society selects a single word or phrase that best represents the mood and interests of online discussions in the previous year. From a nominee list that included “blockchain,” “rogue,” and “digital blackface,” the society has selected “shitpost” as the “Digital Word of the Year” for 2017.

Each January, the American Dialect Society selects a single word or phrase that best represents the mood and interests of online discussions in the previous year. From a nominee list that included “blockchain,” “rogue,” and “digital blackface,” the society has selected “shitpost” as the “Digital Word of the Year” for 2017.

shitpost: Posting of worthless or irrelevant online content intended to derail a conversation or to provoke others.

The overall “Word of the Year,” perhaps unsurprisingly, is actually two of them: fake news.

Shitpost isn’t a judgment of the quality of an online post, though last year certainly offered plenty of objectively shitty content. Shitpost is an example of how people used the internet, in a year that made clear just how powerfully the glut of online information can be weaponized against democracy.

“Much as shitpaper means toilet paper but shit paper means, for example, the Daily Mail, the closed-up spelling of shitpost indicates that it is not just a bad post or the act of posting shittily,” explains Stan Carey on the Strong Language blog. “There’s something else going on.”

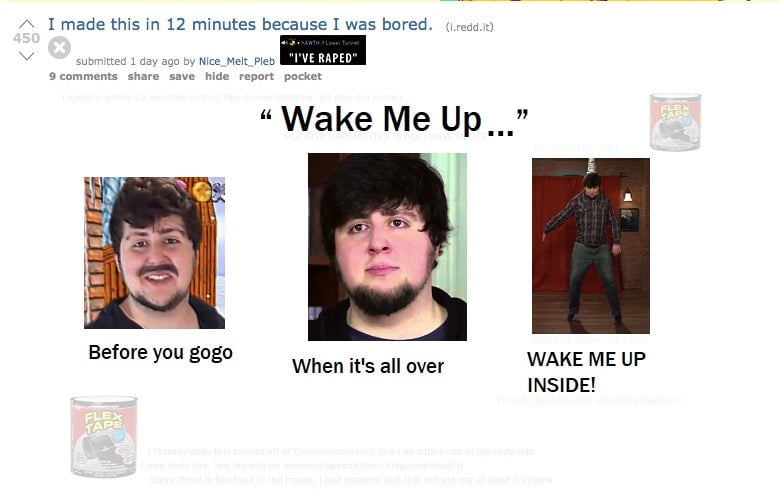

Shitposts are ostentatiously bad contributions to online discussions: poorly Photoshopped memes, unfunny jokes, non-sequiturs, spam. These aren’t misguided attempts at cleverness. They are deliberate efforts to confuse and hijack a dialogue, and while they can show up anywhere, they’re most powerful when applied to politics.

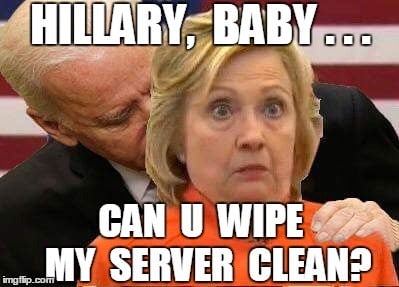

The sudden appearance of the cartoon character Pepe the Frog in Twitter replies and comments in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election was an example of shitposting. Shitposts got a wealthy backer that year as well, when Oculus founder Palmer Luckey funded a group whose stated purpose was to flood the web with anti-Hillary Clinton memes like these:

Shitposts draw attention away from what’s really going on. The time it takes to say “What the hell is this cartoon frog doing in my mentions?” is time that isn’t spent engaging with the issue at hand. It’s a perfect word for a year in which it became evident that we can’t just question what we see on the internet, but why we’re seeing it in the first place.