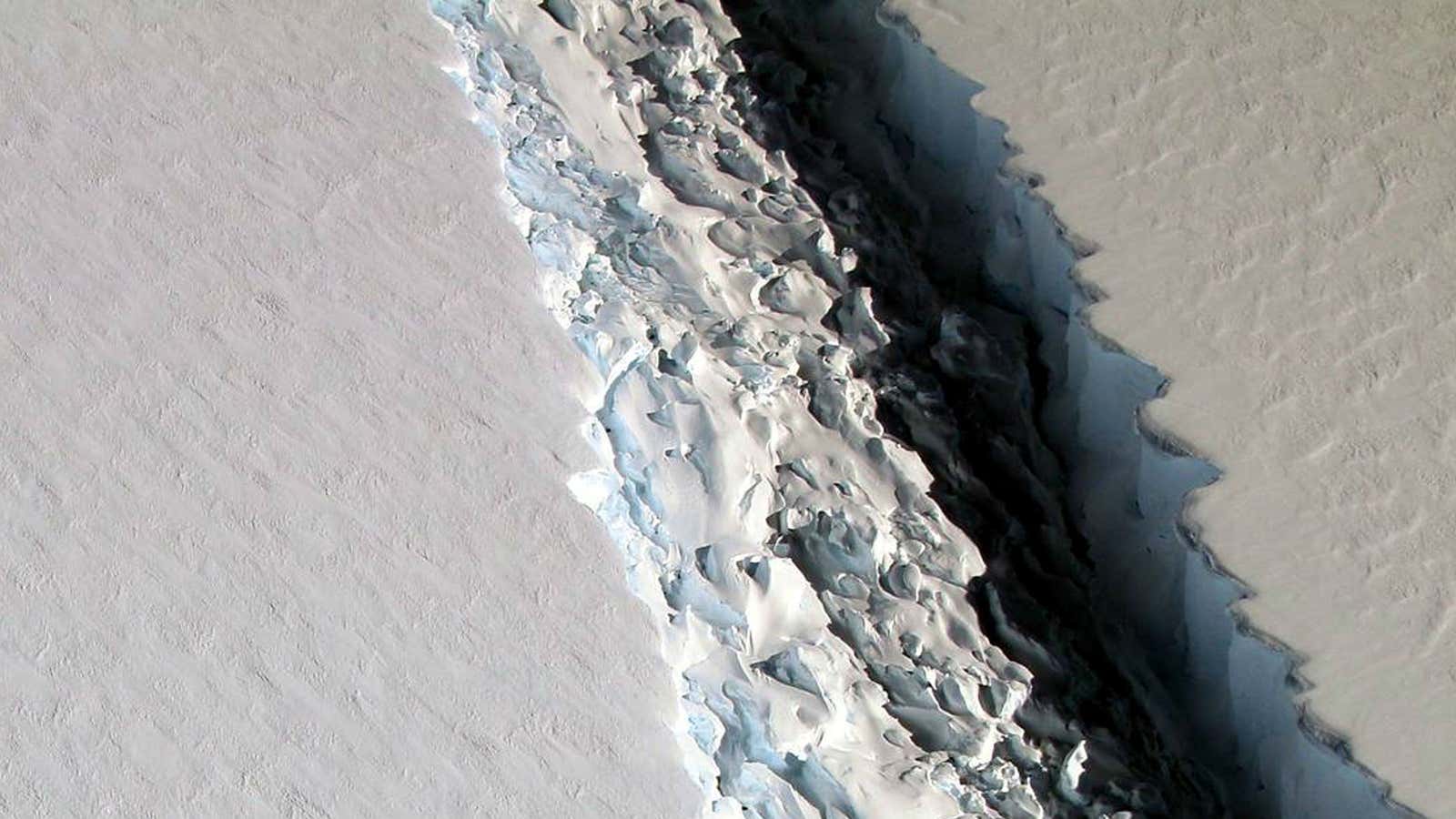

When A-68, a trillion-ton iceberg the size of Delaware (or ten Madrids or two Luxembourgs, whatever you want to call it), parted ways with the Antarctic Larsen-C ice shelf in the summer of 2017, it was the largest recorded calving in history.

The break reduced Larsen-C to its smallest size in recorded history. Though the event can’t be directly attributed to climate change, it is suspicious that the ice receded the fastest it had in years in the months preceding the final break during the dead of winter, when temperatures would normally be their lowest.

Without the protection of the A-68’s ice, almost 3,600 sq miles (6,000 km) of Antarctic ocean water are now exposed to sunlight and accessible for the first time in more than 120,000 years. Today (Feb. 14), a team of researchers led by the British Antarctic Survey will head down to Antarctica to prepare for a three-week mission starting Feb. 21 to explore a 2,200 sq mile portion of the newly accessible region.

The team plans to make observations at all levels, taking notes on the marine mammals and birds that have started swimming near the surface, and the microbes and other lifeforms lurking on the seafloor. Cameras and sleds will collect deep-water video footage and scoop up samples of other tiny animals that have made their homes in frigid waters.

Any ocean research is difficult because of the logistics required getting personnel and gear out on the water. Getting to this region of Antarctica will be particularly treacherous. Temperatures average around 15°F (-9°C), and the water is filled with huge chunks of ice. But it’s necessary work. ”It’s important we get there quickly before the undersea environment changes as sunlight enters the water and new species begin to colonize,” Katrin Linse, the marine biologist leading the expedition, said in a British Antarctic Survey press release.

USA Today compares these waters to exploring an alien world, and for good reason—scientists have no idea what kinds of creatures can survive under the protection of an ice shelf, because the depths have been impossible to reach. The only clues they have to go on are from a recent Greenpeace submarine mission that showed the sea floor was “carpeted with life.” This research saw rare squid, starfish, and more that probably won’t survive when the waters change with their new exposure to surface light and different species that may settle into the new marine real estate.

The team has 21 days on the research ship before the need to return home. This area is protected under an international agreement called the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), which allows researchers to visit to collect information about newly exposed ocean from calved icebergs.

The hope is the team will gain deeper insight into the life that lives in frigid Antarctic waters—and how to protect it if it become threatened by further ice breaks and melting sea ice.