A landmark court case affirms that street art is high art

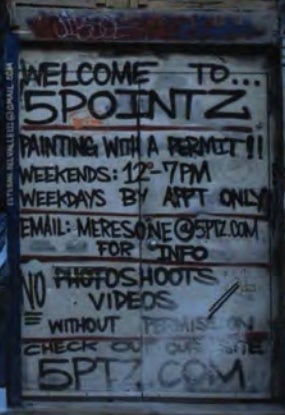

Once upon a time in Long Island City, Queens, there stood a warehouse turned public art gallery called 5Pointz, displaying hundreds of ever-changing paintings. It was visible from a distance, and known the world over. For 20 years, artists and tourists flocked to the graffiti mecca to create and enjoy the outdoor aerosol art show, which helped transform a derelict neighborhood into a desirable place to live.

Once upon a time in Long Island City, Queens, there stood a warehouse turned public art gallery called 5Pointz, displaying hundreds of ever-changing paintings. It was visible from a distance, and known the world over. For 20 years, artists and tourists flocked to the graffiti mecca to create and enjoy the outdoor aerosol art show, which helped transform a derelict neighborhood into a desirable place to live.

Today, condos stand where the warehouse once did. The paintings are gone, and the show is over. But the legacy of 5Pointz is still influencing the culture—particularly in light of a New York federal court’s decision this week, which ordered a real estate developer to pay $6.75 million for destroying 44 aerosol art works of recognized stature on the walls of 5Pointz in 2013.

The verdict in Cohen v. G&M Realty, announced on Feb. 12, is a big symbolic victory for graffiti. It’s the first time a claim for aerosol art under the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA) has ever been tried and concluded by a federal court. ”It’s a milestone for street art, giving legitimacy to the artists’ work, and a true dollar value,” says Dean Nicyper, a partner at the international law firm Withers and former chair of the New York Art Law Committee. He watched the case closely, and told Quartz on Feb. 13 that the positive outcome for the painters is clear evidence that “street art’s time has come.”

VARA grants artists “moral rights” to works of prominent stature, allowing them to sue to protect creations or be awarded damages if recognized works are destroyed—even if the art, or the building it’s on, are owned by someone else. Other such claims have been settled out of court before. But Judge Frederic Block’s opinion discusses the evolution of graffiti and the reasoning behind the legal protection, providing precedent for future suits to follow.

The decision is also significant because it weighs cultural considerations heavily, says Nicyper. It’s rare legal recognition that even when an artwork is hard to price precisely—like when it’s on a building and difficult to remove—it can still be recognized as extremely valuable culturally. That’s a dramatic finding, especially in the context of a case about graffiti and real estate development.

Rise of a form

Judge Block told Quartz on Feb. 13 that he cannot comment on the case. Still, based on his written opinion, he sees graffiti as high art.

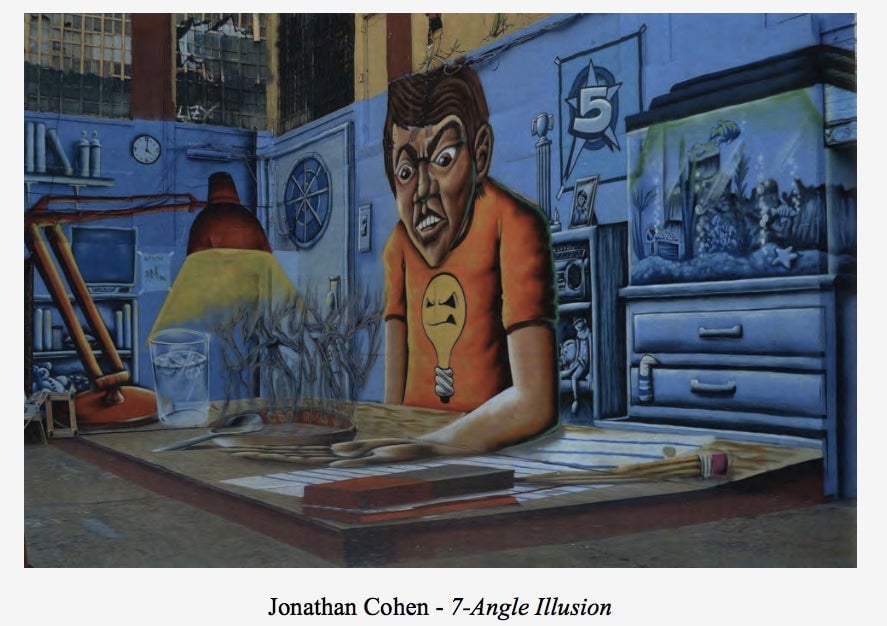

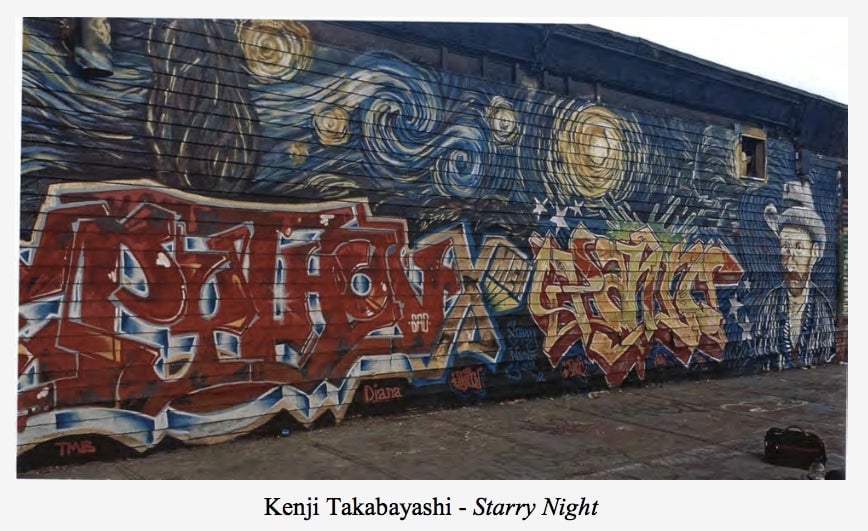

A Brooklyn-born musician and fiction writer, the judge wrote admiringly of the aerosol artists and their 44 destroyed works. “They reflect striking technical and artistic mastery and vision worthy of display in prominent museums if not on the walls of 5Pointz,” the opinion states.

Notably, the decision is guided by a jury’s counsel. Dismissed by the parties after evidence was presented over three weeks last November, the judge kept jurors on in an advisory capacity. Block wanted the jurors’ opinions because VARA is about perceptions of art. He discovered that New Yorkers see some graffiti as important cultural works. Jurors advised finding for the artists, reflecting a changing understanding of how the.wider culture perceives street art.

By contrast, Block expressed disappointment with Gerald Wolkoff, the building owner. In 1993, Wolkoff granted artist Jonathan Cohen permission to transform a derelict building into a street art center. But in 2013—after Cohen and countless other artists revived the surrounding neighborhood over two decades—the developer whitewashed 5Pointz while a suit for the right to salvage the art was pending.

Indeed, the reason Wolkoff owes the 21 artist-plaintiffs so much money is because he took matters into his own hands. He was ordered to pay the maximum statutory damages for his “willful” destruction, up to $150,000 per work as opposed to $500-$20,000 per work for a non-willful VARA violation.

Wolkoff argued that the artists knew someday the painted warehouses would be replaced by high-rise residential condos. Even so, the court said this doesn’t justify his decision to whitewash 5Pointz in 2013 while the case was under consideration. ”If not for Wolkoff’s insolence, these damages would not have been assessed,” Block writes. The judge notes, too, that the very expensive lesson is meant to send a message to physical property owners that they can’t just mess with important intellectual and cultural property without consequence.

By whitewashing 5Pointz on a whim, Block notes, Wolkoff deprived the world’s art lovers of an opportunity to bid adieu to the iconic works. “The shame of it all is that since 5Pointz was a prominent tourist attraction the public would undoubtedly have thronged to say its goodbyes…and gaze at the formidable works of aerosol art for the last time,” the opinion states. “It would have been a wonderful tribute for the artists that they richly deserved.”

Mixed blessings

The ruling is important, legally and culturally speaking, because it affirms the fact that street art can also be high art of public interest, though its roots are in vandalism. Art lawyer Nicyper, who represents galleries, auction houses, artists, and also building owners in possession of recognized works of street art, explains that Block’s opinion shows the flexibility of VARA standards. Now we know that graffiti can qualify as “artistic work of recognized stature,” and there’s a legal opinion laying out the relevant considerations in this kind of case.

But the news isn’t all good for artists. Nicyper also told Quartz that the ruling could have a chilling effect on building owners, who won’t want to let artists paint on walls if they’re worried these works will limit their ability to sell or redevelop properties later. Wolkoff and the artists at 5Pointz were in agreement for 20 years before their mutually beneficial art project devolved into a lawsuit. That might make property holders wary of sharing with artists.

As it stands, possessing a notable work of street art can be problematic even when the owner wants to save the painting. Nicyper, for example, once tried to help a client offload a Banksy on a building to a museum. He learned the hard way that removing works of street art is very expensive and that can make it difficult to even give them away; he’s not sure what happened to that Banksy in the end.

The feeling on the street is similarly mixed. RJ Rushmore, editor of the street art blog Vandalog, told Quartz in a Feb. 13 email, “It feels good to see the courts recognizing graffiti as art worthy of legal protection.”

But Rushmore has concerns over the verdict, too. ”If I’m asking a property owner to let an artist paint their building, I don’t want her worried that she’s suddenly handing over control of her property to someone who might turn around and sue her,” he says. Rushmore could discuss law, waivers, and the facts of the 5Pointz case, however it won’t be very inspiring. “That’s not the discussion I want to get into when I’m trying to get a wall owner excited about a possible mural,” he explains.

The street art afficionado also points out that this case was about works created with the building owner’s permission, which isn’t really how the bulk of graffiti gets done. The most interesting question, he says, has yet to come up: Whether VARA could be used to protect a recognized art work painted without an owner’s blessing. “Nobody’s tested VARA on works painted without permission, and those, hopefully, are the artworks at the heart of street art and graffiti culture,” says Rushmore.

Still, the 5Pointz verdict is heartening to artists. For Vexta, an Australian invited to paint at 5Pointz before it was whitewashed, who ultimately couldn’t because of Wolkoff’s actions, this decision feels like a victory.

“I think the verdict is incredibly important,” she wrote to Quartz in an email on Feb. 13. “Not only does it put the power back into the hands of the artists…it also shows the value and importance of art and graffiti in the public realm, [and] is a clear and strong statement on how incredibly important the history of graffiti and its community is to New York City.”