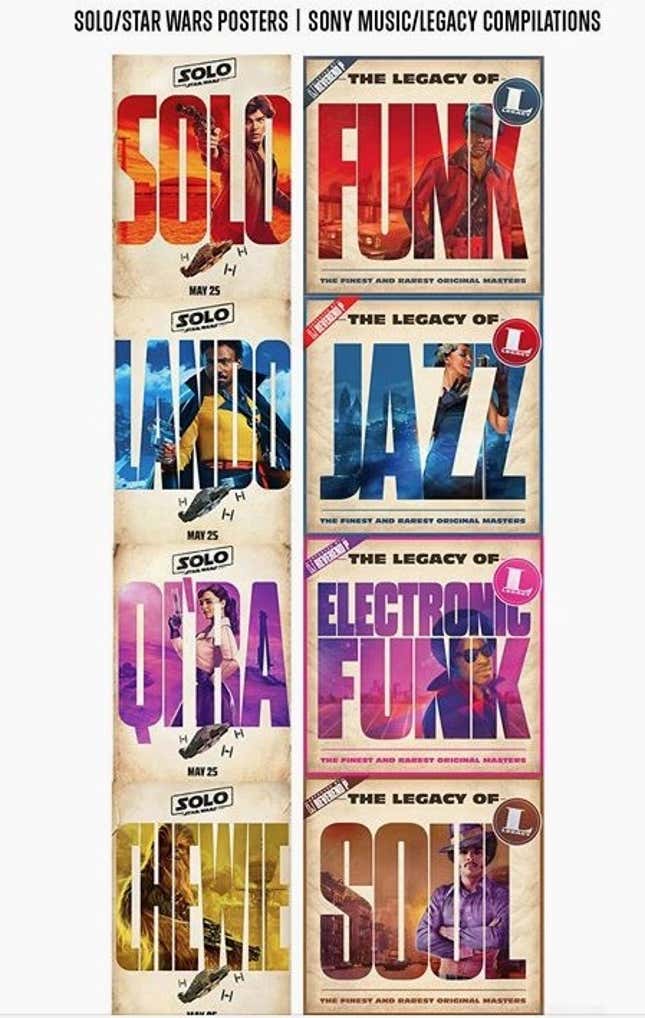

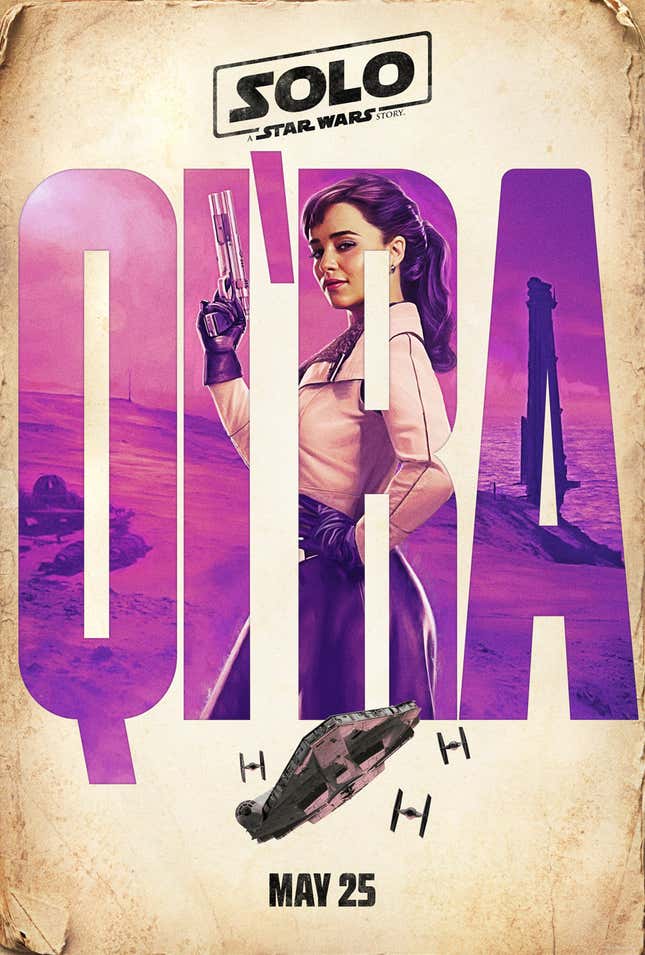

When Disney released four teaser posters last month for Solo: A Star Wars Story, the stylized, retro portraits may have helped stoke excitement for the next Star Wars installation—but they didn’t thrill one graphic designer in France.

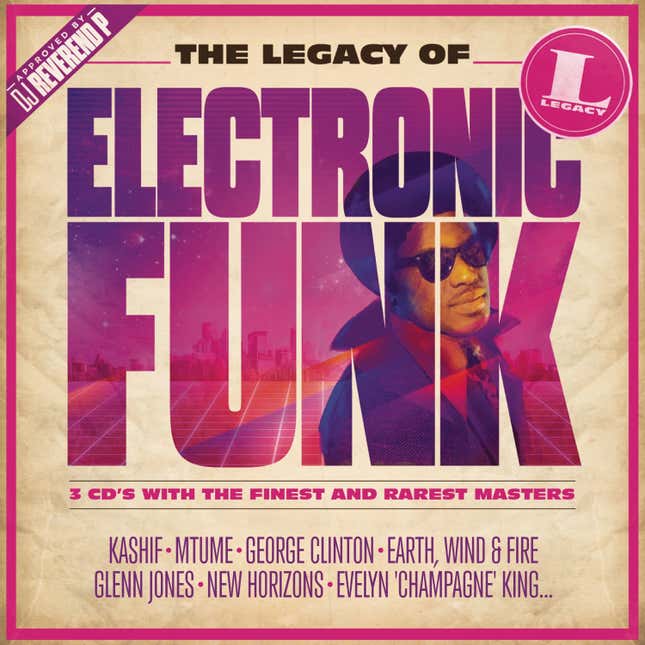

“I am flattered that the quality of my work is recognized, but it is still pure and simple forgery,” wrote Hachim Bahous on his Facebook wall on March 2. The Lille-based designer juxtaposed the Star Wars posters with CD covers he created for Sony Music France’s Legacy Recordings series in 2015—making a convincing visual case for plagiarism. “I have not been asked for my permission,” he continued. “I wish to be credited and paid for this work I have done for Sony!”

Bahous ended the post, written in French, with “#LegacyofStarWars”—a challenge to the integrity of the beloved sci-fi franchise.

After garnering widespread attention over the weekend, Bahous deleted the accusatory Facebook post (or changed its settings to private) yesterday. Disney told The Hollywood Reporter that it is investigating the provenance of the posters which, according to the caption on IMP Awards, was created by the Hollywood-based design studio BLT Communications. Bahous, Disney, and BLT Communications haven’t responded to Quartz’s inquiries.

Copycat graphic design isn’t uncommon

Bahous is hardly the first graphic designer to see his work seemingly rehashed by another entity. In one high-profile case, Belgian designer Olivier Debie sued the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Committee after demonstrating similarities in the design of the first version of the games’ logo with an emblem he designed for Théâtre de Liège years before. After the allegations, the Japanese committee scrapped the logo, and launched a public contest for a new one.

Imitation is an inevitability, says graphic design historian Steven Heller. “If something is good, it will knocked off,” he says. “Look at I ❤ NY. Look at Coke and Pepsi. Look at the ripoffs around the world for Starbucks.”

Heller says there appears to be enough visual similarities between Balhous design and Disney’s posters to make it seem like a copy: the condensed fonts, the weathered, textured background, the color palette, and the photo treatment of characters from the movie displayed inside the letters.

It’s worth noting that the technique of displaying photos within letters (“image fill” in graphic design parlance) isn’t Balhous’s invention. Decades before Adobe released the software that now allows designers to achieve this effect in a mouse few clicks, graphic designers including Paul Rand, Herb Lubalin, and Saul Bass were already using it in their work. ”That’s one of the most common [techniques],” Heller observes. “So much so we don’t know who did it first.”

Gail Anderson, a designer of award-winning posters for the entertainment industry, says there’s a reason this image treatment is often used: “It’s a common way to get some art into movie and theater posters.” Still, she said, ”admittedly, these samples are pretty similar.”

Challenging big companies

Often, what appears to be a cut-and-dry case of copyright infringement isn’t so simple to prove in court, explains attorney Barry F. Irwin, founder of Irwin IP and vice president of Lawyers for the Creative Arts, a Chicago-based artist legal aid organization.

Designers need to satisfy two criteria to win a court case: They need to show “substantial similarities” (which Bahous arguably does in his Facebook post), and they need to prove that the designers had access to the original design work (in this case, his Sony CD covers). This could involve asking the Star Wars poster designers to show their inspiration boards or unpack their conceptual process at the trial. An added complication is the fact that Bahous is in France and there’s is no “international copyright” standard followed by all countries, as the US Copyright Office explains.

The prospect a lengthy court case to defend one’s work can be daunting for many busy, resource-poor solo designers who just want to get on with their other projects—and corporations know this. “A lot of times big companies, especially when they’re up against an individual, would rather fight the litigation than to settle it because they know that the smaller player on the other side is unlikely to afford the cost of litigation,” explains Irwin.

But this shouldn’t deter designers from asserting their rights, he says. “You can find attorneys who are willing to take cases on a pro bono or a contingency fee basis,” says Irwin. (His organization, for example, offers pro bono legal work, education services, and low-cost dispute resolution, and is one of several similar organizations in the US.) “That’s the only way you [designers] can really afford to pursue these cases. You’re going to spend a lot more in legal fees if you were to pay the lawyer out of pocket than you can expect to gain in litigation.”

Given the daunting legal process, it’s no wonder designers are turning to the court of public opinion—on social media as well as the press—to make their cases. Often, that’s enough to shame corporations into addressing the problem.