In the weeks since a fellow student shot and killed 15 classmates and two staff members on their campus, the students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, have responded to tragedy with striking courage. They have taken on a powerful industry and stood up to lawmakers and a US president. In many ways, they are directly carrying on the legacy of the woman for whom their school is named.

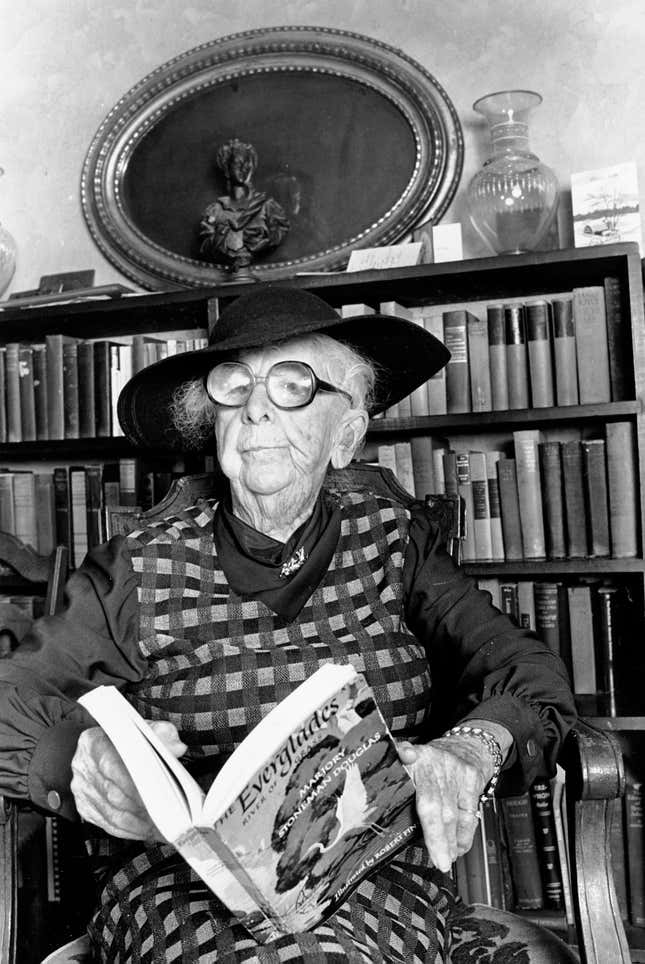

Until her death in 1998 at the age of 108, Marjory Stoneman Douglas was a tireless journalist and advocate—first for women’s suffrage in the early part of the 20th century, and then for the environment. Her work on behalf of the Florida Everglades was instrumental to the area’s designation as a national park in 1987.

Her convictions brought her into conflict with the powerful development lobby and the politicians it funded—opposition she met with steely determination. Jeered at a 1983 public hearing, Douglas (then 93) retorted, “Look. I’m an old lady. I’ve been here since eight o’clock. It’s now eleven. I’ve got all night, and I’m used to the heat.” Ten years later, Bill Clinton awarded her the US Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Both the Parkland students and their school namesake have spoken out bravely for their convictions, and both have defied attempts to marginalize them: Douglas for her gender, the students for their age. Writing in the Miami New Times, journalist Travis Cohen elegantly summarized the character of their shared courage:

For both Douglas and the Parkland students, there was and is a need to be a fighter, to be unflinching in the face of resistance from the powers that be, but also to be incredibly smart—far smarter than the opposition, because that opposition was never fair to Douglas, and it certainly has never been fair to youths . . . Just like Marjory Stoneman Douglas before them, they have decided that if this is going to get done, they are going to have to do it on their own. And just like she did, they have gone out and begun changing the world themselves.

The Majory Stoneman Douglas High School students’ advocacy is also a reminder of why schools and buildings are named for people in the first place. In a 2007 essay, a trio of educators noted a trend toward naming US public schools for natural features like animals or creeks instead of public figures. Naming schools for things instead of people may avoid controversial debates, both at their founding and in the future. Students have spoken eloquently in recent years against public figures whose problematic legacies betray the values of the institutions that bear their names.

But relegating history’s most courageous figures to footnotes instead of building fronts also deprives students of the opportunity to draw courage and inspiration from those who went before them. A namesake building is a lovely tribute to a well-lived life, of course. But the new generations of fighters that name might inspire is an even better one.