As the #MeToo movement rocks South Korea, taking down one powerful man after another, a novel about one woman’s struggle in Korea’s patriarchal society is back in the spotlight.

This month, Irene, a member of the girl group Red Velvet—which will perform in Pyongyang this weekend—faced an online backlash after she told a fan meeting that she’d been reading Kim Ji-young Born 1982, a book that quietly chronicles all the small ways women experience being “less than” in Korea. Some fans reportedly burned her pictures.

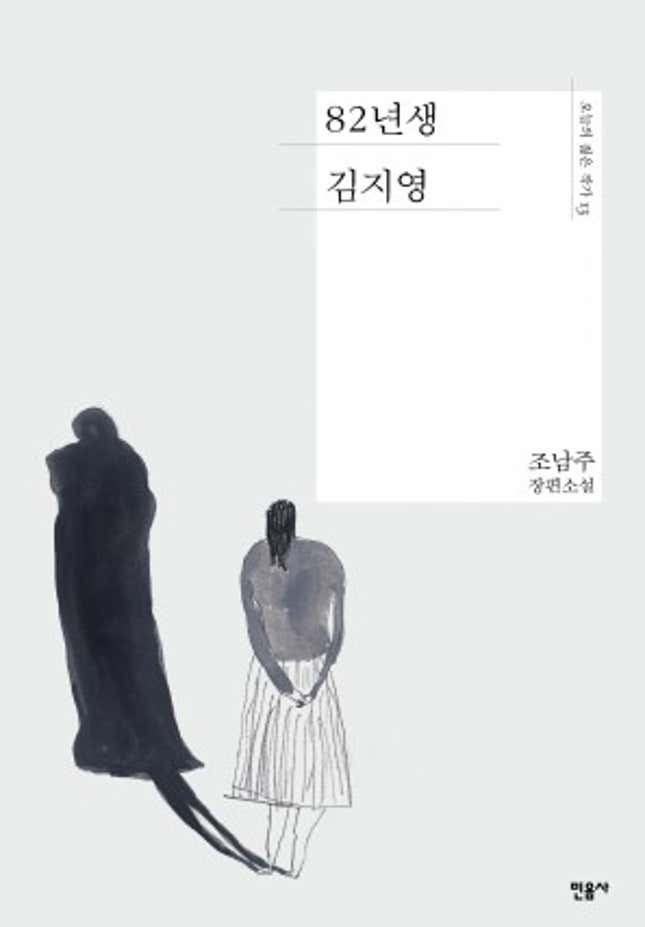

Published in October 2016, the book was written by Cho Nam-joo, a former television scriptwriter, who drew in part on her own experience as a woman who quit her job to stay at home after giving birth to a child. The book tells of a woman in her early 30s, Kim Ji-young—an exceedingly common Korean name—who, like Cho, is well educated, and also quits her job once she has a baby. As the years progress, Kim finds herself increasingly possessed by other people’s spirits, such as her mother’s and a dead colleague’s.

She starts to display characteristics that are, by Korean standards, unseemly of a good wife, mother, and daughter-in-law, for example by complaining to her in-laws that she is never allowed to visit her own parents during Korea’s Thanksgiving festival—which married Korean women are expected to celebrate with their in-laws. In response to her outbursts, her husband decides to take Kim to see a psychiatrist, a plot line reminiscent of 2016 Man Booker International Prize winner The Vegetarian by Han Kang, which uses a Korean woman’s extreme turn to vegetarianism as an allegory for the struggle to fight against patriarchal societal norms.

A little over a year after the book’s publication, Korea is in the throes of the #MeToo movement (also known as #WithYou in Korea), and the pace with which it has unfolded has been shockingly swift. A former presidential hopeful and ally of Korea president Moon Jae-in, Ahn Hee-jung, now finds himself under investigation following allegations of rape made against him by a female secretary (Ahn first denied the allegations but then later apologized). A former lawmaker shelved his plans to run for Seoul mayor after he was also accused of sexual harassment. A number of well-known cultural figures such as directors, TV stars, and a monk-turned-poet often seen as a Nobel literature contender, have also been embroiled in sexual harassment accusations.

But #MeToo’s unabated march in Korea is also deepening gender fault-lines, which are rooted in Korea’s conservative culture but have intensified in recent years, particularly online, as economic and demographic realities start to shift. Some men, for example, have responded to #MeToo by choosing to freeze women out of workplace activities—the “Pence rule,” named for the US vice president’s own practice of minimizing fraternizing with women—potentially further hurting women’s professional prospects. Others have compared #MeToo to being a witch hunt, particularly as two men—an actor and a university professor—took their own lives after sexual harassment accusations were made against them.

Some men who believe that #MeToo is stoking sexism against men are using the hashtag #YouToo to tell their own stories of harassment, for example—and Cho’s book has also drawn ire from these quarters.

A group of Korean men started crowdfunding for a project to produce a novel called Kim Ji-hoon Born 1990. The project said it hoped to shine a light on discrimination against men in Korea, such as the fact that only men need to perform military conscription. The project was pulled in the end (link in Korean).

Cho’s book isn’t a raging manifesto by any means, but the reaction to it from men who feel besieged by #MeToo is a symptom of the kind of pushback women face for what might be seen as innocuous acts elsewhere. Apart from Red Velvet’s Irene, another K-pop star from female group Apink faced an outcry from male fans for using a phone case emblazoned with the message “girls can do anything.”

Some who have read Kim Ji-young Born 1982 describe the book as lacking in exciting plot developments, but as Cho, the author described in an interview, it was precisely through everyday, seemingly ordinary incidents that she wanted to use to illustrate the injustices faced by Korean women. For example, Cho said she was called a mom-chung, a hybrid Korean-English term meaning “mom worm” used to describe women who housewives who enjoy comfortable lives on their husbands’ earnings, while she was with her daughter in the park.

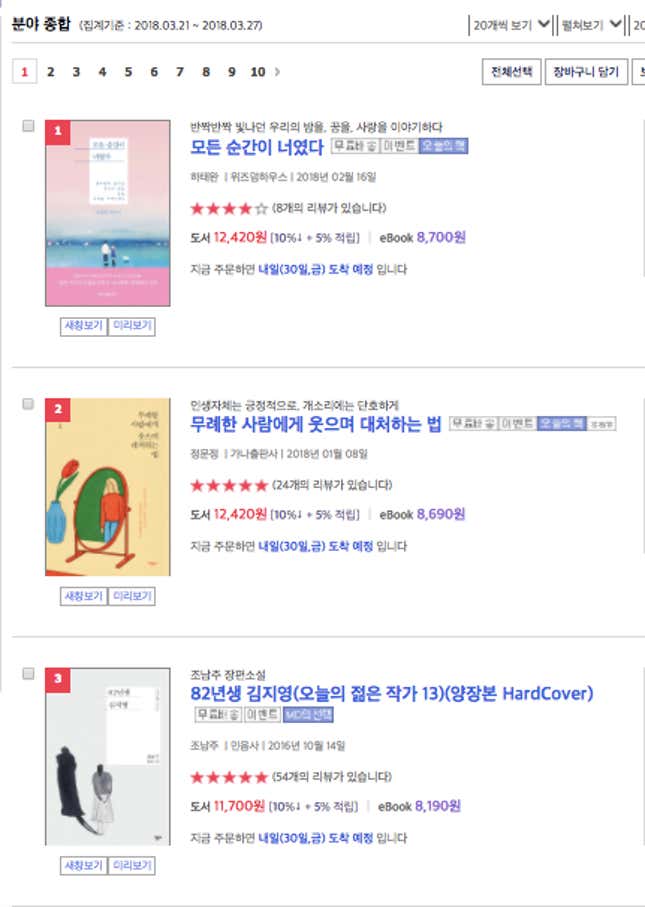

Kim Ji-young Born 1982 appears to have gained in popularity in the past year compared to when it was first published, as #MeToo took off in the US in response to allegations against studio executive Harvey Weinstein, and then spread globally. It was the second-best-selling book (link in Korean) for Korea’s biggest bookstore chain in February, and its third-best-selling book in the week ending March 27.