Media outlets—ourselves included—have made fun of new rules that will allow private companies and hedge funds in the US to advertise that they’re raising money. Those rules, lifting a ban on “general solicitation,” are part of the JOBS Act passed last year, and go into effect today. But as funny as the new rules may seem (A hedge fund, advertise on a billboard?), they could be transformative. And their effect on hedge funds is the least important reason.

Since the 1930s, the US Securities and Exchange Commission has drawn a sharp distinction between public and private companies. Public companies advertise the fact that they’re raising money by being listed on a stock exchange. Private companies have to keep their fundraising plans hush-hush. Up to now, not only could they not put their fundraising goals on their website; would-be investors couldn’t simply call up a start-up or fund out of the blue and ask if they were raising money. They had to have a vaguely defined “pre-existing relationship.” This meant investors needed either to be familiar with the start-up scene, or have a broker to make introductions.

“If you’re not a client of Goldman Sachs or JP Morgan you may not have access to the deal flow,” explains SecondMarket’s Mark Murphy, who was part of the effort to lift the ban on general solicitation. “Particularly if you’re not located on the coasts—basically New York or Silicon Valley—you’re not going to have access to those opportunities.”

The SEC’s supervision of investment in private companies has also up to now been pretty lackadaisical. Though they were supposed to file documents with the SEC while raising a round of funding, some companies didn’t know or forgot. And while investors were supposed to be “accredited investors,” meaning someone with a net worth higher than $1 million (not including her primary residence) or with an income greater than $200,000 for each of the previous two years, they didn’t have to produce documents to prove it. And according to insiders, the SEC didn’t really care that much.

That’s all about to change. The new rules allow private companies to tell whoever they want that they’re looking for funds, but also bear the burden of filing paperwork in a timely manner and making sure any would-be investors are really accredited.

The upshot is that a lot more of the 8.5 million accredited investors (pdf) in the US would be able to invest in private companies. “This is really the most significant change to the capital markets since the 1930s,” says Murphy.

A remedy for IPO fatigue

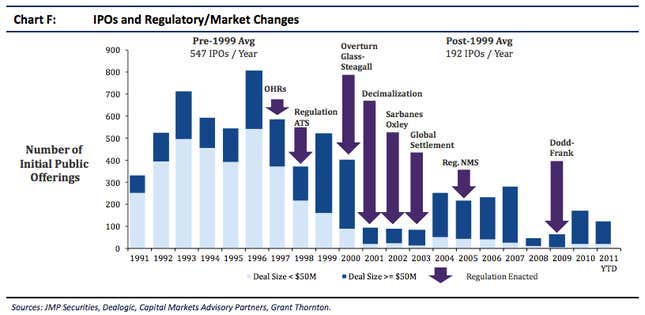

In theory, the new rules are a way to help private companies grow as public markets have become less hospitable. IPOs have become very pricey, particularly as new regulations have passed (see chart below). Instead of going public, more young companies now see a buyout by a bigger firm as the best way both to get a lucrative “exit” for their early investors and to tap resources and expertise that the company needs to develop.

That’s bad for jobs, the SEC said in a 2011 memo (pdf). Such buyouts usually lead to job losses “as the acquiring company looks to eliminate redundant positions between the two enterprises.” The SEC said that, “by one estimate, the decline of the U.S. IPO market had cost America as many as 22 million jobs through 2009.”

But if companies can continue growing without having to take either a buyout or an IPO, the SEC figures, they’ll have more incentives to eventually go public later, bringing new leadership and thinking to the market. This is also the goal of another JOBS Act provision, which will allow a company to have more non-employee shareholders before it’s forced to go public.

But an opportunity for fraud

Skeptics abound, however. Howard Meyers, a professor at New York Law School who formerly worked for the SEC, worries that the new rules will make it easier for shady companies and funds to take advantage of more unwitting investors. ”The idea behind the preexisting relationship [requirement] was that the investor would have access to certain [private] information about the company,” Meyers told Quartz. Since early investors are often family, friends, or sophisticated venture capitalists, he reasons, they are likely to know things private companies aren’t obliged to disclose. So new would-be investors likely won’t have enough facts to make smart investment decisions.

This could be a recipe for disaster, Meyers thinks. “In some way this [rule] gives a stamp of approval…It adds an air of legitimacy to these potential frauds.”

Meyers and some other experts surveyed by the Government Accountability Office (pdf) suggested that raising the bar for being an “accredited investor” could be a way to prevent fraud. The $1 million net worth and $200,000 yearly income requirements were first instituted in 1982, and have been modified only slightly since. At the very least they could be raised in line with inflation; $200,000 in 1982 would have been worth $488,512.77 today. Both the GAO and Meyers also suggested using criteria other than net worth and income to determine whether an investor is sophisticated: for example, working in conjunction with a registered financial advisor or taking investment competence tests.