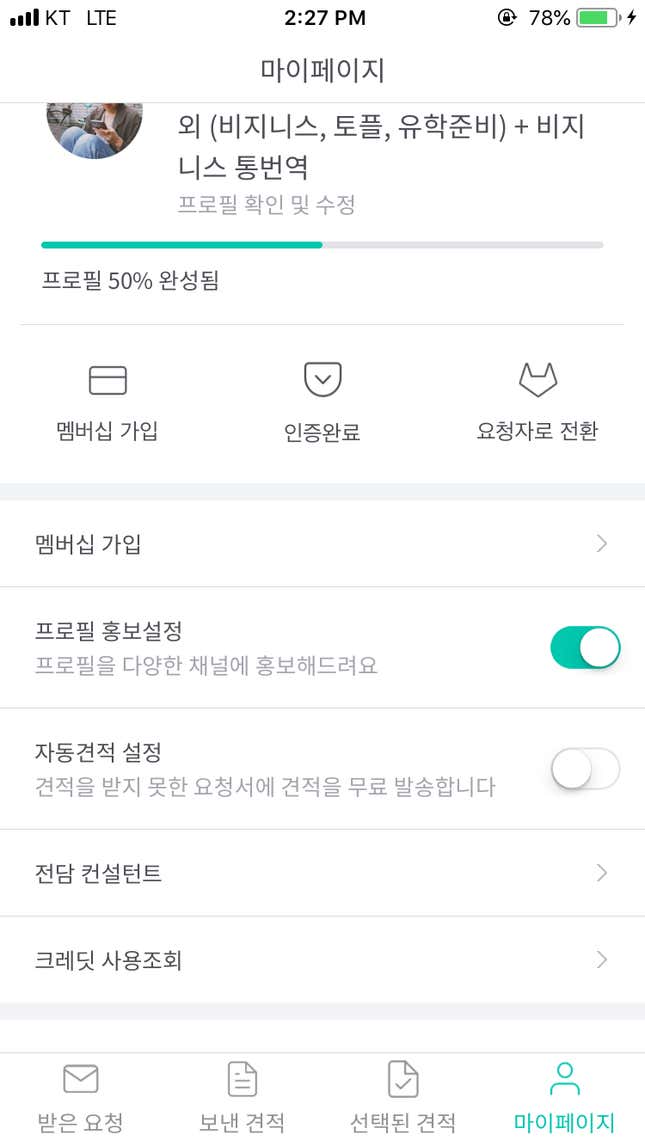

A few weeks ago, I downloaded a South Korean app called “Soomgo,” a shortened Korean word for “Soomeun Gosoo,” which means “hidden master.” Soomgo, and its rival Kmong, are Thumbtack for South Korea—a marketplace for matching users with local service providers, such as designers, movers, and English tutors, for short-term jobs.

Both gig economy platforms are very popular—Kmong has more than 25 million users as of April 2018, while Soomgo has clocked up more than 50 million as of March—and they’ve become a new avenue for outsourcing academic fraud, seamlessly connecting students with ghostwriters.

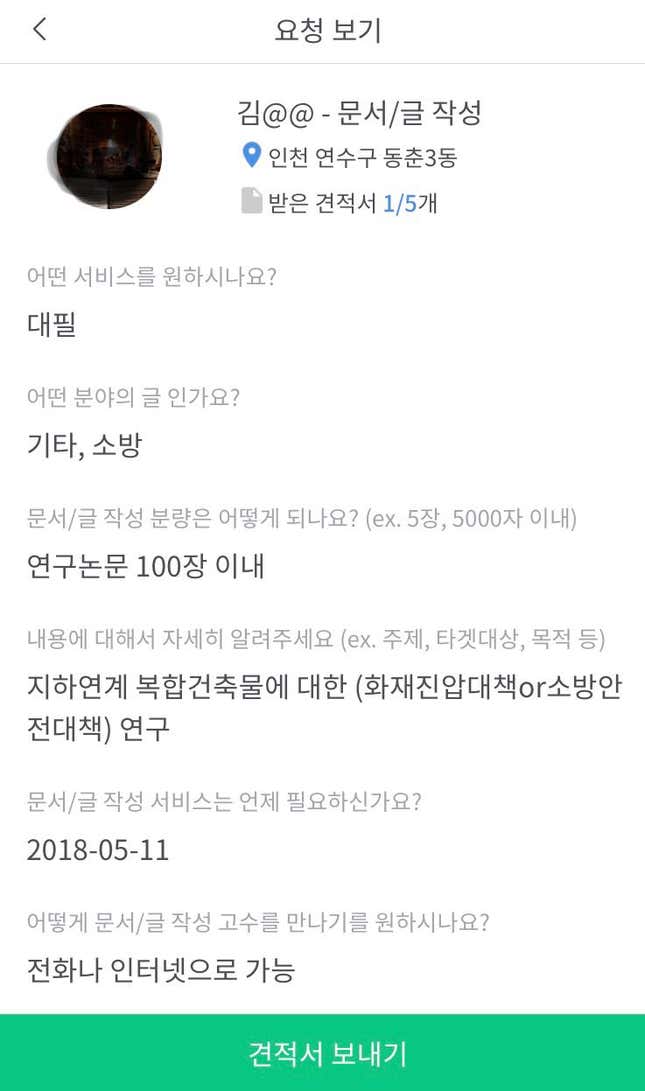

Within a few weeks of signing up as a tutor and English translator, dozens of requests piled up in my Soomgo inbox—and about 20 unexpected messages. They were ghostwriting requests for theses and dissertations. For example, one student offered me the equivalent of $2,000 to write her 80-page thesis on e-learning for Korean language education. Ghostwriting requests have made up more than one-third of the overall inquiries I’ve received.

Ghostwriting has become a lucrative market as more South Korean university graduates go on to graduate school to gain an edge, or buy themselves more time to look for a job in the country’s competitive job market. The number of South Korean graduate students has steadily increased from 296,576 to 326,315 from 2007 to 2017. The country’s youth jobless rate stood at a record 9.9 percent last year, according to government data.

While plagiarism and cheating are rocking higher education in many countries, often enabled by the internet, fraud in South Korea’s academia permeates all levels. Professors have been caught ghostwriting for their students. A lecturer accused a full-time professor of making him ghostwrite his papers. Politicians have been busted for hiring ghostwriters for their dissertations, while the South Korean education ministry recently said it found that some professors had listed their children as co-authors—perhaps to give them a head start up the ladder of academic qualifications.

It turned out that I wasn’t the only one who had received such dubious requests.

Park Hyo-jin, a freelance editor who is one of Soomgo’s more than 100,000 registered service providers, said he had received many ghostwriting inquiries since joining the platform in September last year. “I was taken back that I received more ghostwriting requests than writing class requests,” Park said, adding that he does not accept such requests. “There have been especially lots of requests lately because March to April, and September to October are thesis review season.”

On Kmong, the exchange is more subtle. Although you can find a ghostwriter who explicitly promotes his or her services for pretty much everything—from a movie review, a letter to a spouse, to an academic paper—many ghostwriters on Kmong offer a “consultation service.”

The apps add to a ghostwriting market that already includes numerous websites providing consulting services for academic papers, like Dream Sherpa, which likens itself to a sherpa “essential for climbers to conquer Everest.” The company provides a comprehensive eight-step service for an academic paper—from formulating a topic and methodology to preparing for thesis defense. While these companies emphasize the legality of their consultations, various local media have reported that some offer ghostwriting services under the table.

Two “consultants” from Kmong specializing in “researching and editing” both confirmed that they provide ghostwriting services when I privately messaged them, even though one of them explicitly states on his public profile that he doesn’t offer ghostwriting.

“I have 100% success rate. Twelve dissertations I’ve partially and fully written for the second semester of 2017 were all approved [by the school]. The undefeated track record is to be continued!” one ghostwriter exclaimed proudly in the introductory document he sent me via Kmong with a quotation. He charges $5,000 for a 50-page graduate thesis, and $12,000 for a 100-page doctorate dissertation. He said there’s an extra charge for writing a dissertation for the top three universities in South Korea—Korea, Yonsei, and Seoul National University—since these would require substantially more work.

Both apps offer almost full anonymity as all conversations take place within the apps’ chat rooms. The user has to pay the monthly subscription fee to call the service provider. The numbers are encrypted.

I reached out to several users who requested ghostwriting services from me for an interview but none responded. Soomgo’s head of marketing, Jay Lee, said dissertation writing and ghostwriting aren’t among their official service categories, and that an internal search found only two cases of ghostwriting requests. He noted it was a small fraction of overall requests but said the company would work to close loopholes and prevent misuse of the service.

Kmong did not respond to multiple emails asking if it was aware of the ghostwriting market on its app, and whether it was taking steps to curtail these requests.

Four out of ten (link in Korean) South Korean graduates think ghostwriting is acceptable, according to a survey by local job portal Incruit in 2016. With these potential demands, it’s up to the university to weed out the bad seeds, but many are failing at gatekeeping, according to professor Park Ker-yong of Sangmyung University. “Most of the graduate schools in South Korea don’t require their applicants to take an admission test as many mid- to low-tier graduate schools are in haste to fill their vacancies—admitting students who cannot even write their own papers.”

Yi Yang-ju, a ministry of education official, declined to comment on how the government is tackling these problems. Apps like Soomgo and Kmong are definitely uncharted territory for regulators, who have been struggling to rein in ghostwriting for years.

“I think the economic activity taking place within Soomgo has the characteristics of an underground economy, making it easier for users to request ghostwriting services,” said Park, the freelancer.

Update: This story was updated on June 1 with comment from Soomgo.