Fearing fragile economies, a London hedge fund has started a doomsday fund

Algebris Investments, which oversees €12.3 billion ($14.5 billion) in assets, thinks global economies and financial systems have become increasingly fragile in recent years. As a result, it believes that clients need a way to protect against a panic: A fund that’s designed to profit from a market meltdown.

Algebris Investments, which oversees €12.3 billion ($14.5 billion) in assets, thinks global economies and financial systems have become increasingly fragile in recent years. As a result, it believes that clients need a way to protect against a panic: A fund that’s designed to profit from a market meltdown.

The money manager’s so-called tail-risk fund started trading June 1 and is managed by Alberto Gallo, the hedge fund’s head of macro strategies. For Gallo, years of aggressive monetary policy are reason to worry. Central banks have purchased trillions of dollars of assets to bolster markets and make borrowing cheaper. While that’s helped support an economic recovery, the former Goldman Sachs strategist thinks unwinding the stimulus could get ugly.

“Tail risk” is an expression used in finance to describe a risk that has a low likelihood of happening (like a steep financial crash), but may generate outsize consequences if it occurs. The most severe shocks are sometimes called black swan events, an expression credited to former options trader Nassim Taleb. Until black swans were discovered in Australia, it was assumed all swans were white; likewise, financial market forecasts are prone to ignore unlikely but disruptive possibilities.

Gallo says instability is mounting as investors herd into similar strategies, liquidity (the ease of trading) dries up, and passive investment proliferates. Gallo was among the strategists warning that inverse-volatility bets, which blew up in February, were a ticking time bomb.

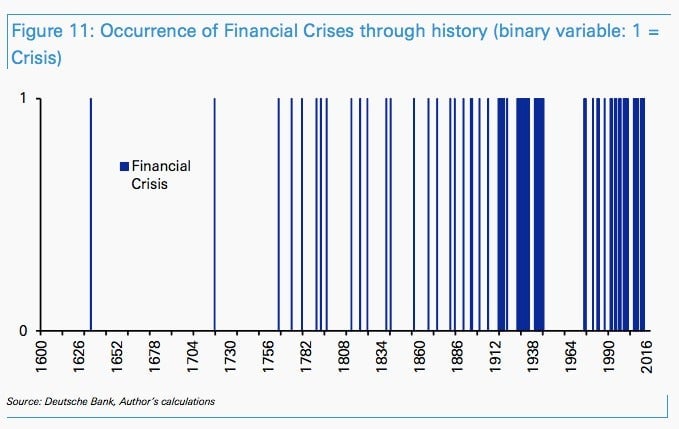

By some measures, financial panics are becoming more common. A study last year by Deutsche Bank argued that crises—although not always as severe as the 2008 crisis—remain difficult to predict in advance despite their increasing frequency. Like Gallo, the German bank’s researchers suggest that the next implosion may be provoked by the world’s major central banks.

Tail-risk funds became increasingly popular after the 2008 financial crisis. This isn’t surprising, given that investors are most mindful of financial panics just after one happens. Enthusiasm for these funds faded in the years that followed as markets remained placid. The sudden spike in volatility in February, however, generated impressive gains for some of these specialty funds, which often invest in options linked to price swings, or volatility. The Algebris fund will bet against government and corporate debt, stocks, currencies, and commodities.

For tail-risk strategies, a key is to lose as little as possible during the dry spells—that is, most of the time. Gallo told the Financial Times (paywall) that he’s ready to wait three-to-four years for the strategy to pay off. The fund’s management fee will be less than half the usual hedge fund charge, and he said its share of any profits will be curtailed, which may make the fund more palatable for investors.

In the meantime, Gallo told the newspaper that there are a range of things to fret about: Geopolitical hiccups, a renewed euro zone crisis, a spike in oil prices, and heavy corporate and government debt burdens. Deutsche Bank’s frailty is also worrying, and market turmoil in Italy and Brazil could cause trouble. Nobody knows for sure what will end the current streak of economic growth, but—as the saying goes—all good things must come to an end.