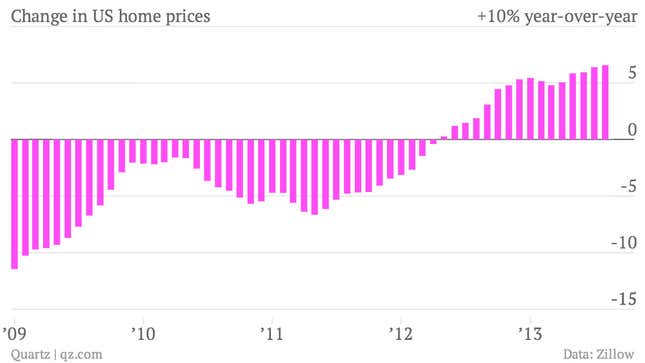

We’ve begun to see signs of a nationwide slowdown in the pace of home value appreciation, and that’s a good thing. The question going forward is whether political debates will lead to too much of a good thing and prevent moderation from turning into normalization. As Matt Philips’ noted in Quartz last week shows, housing prices are still going up but their pace of growth is definitely slowing down.

Zillow’s own data show that after the monthly pace of home value increases rose to 0.9% in May, we’ve witnessed three straight months of slowing monthly gains. This trend should continue as mortgage interest rates rise, investors exit the market and more homes are made available.

Even as this occurs, increasing household formation rates and the continued unwinding of doubled-up households created by the housing recession should keep demand at a level sufficient to support this slower pace of appreciation. Zillow expects annual home value appreciation to fall from 6.4% in August 2013 to 5.2% by August 2014, and to lower rates more in line with longer-term historic norms of between 3% and 4% beyond that.

The robust bounce off the bottom experienced since late 2011 has been great, but the breakneck appreciation we’ve seen in many areas is unsustainable. If prices rise too fast, they outpace income growth and impact affordability. This is less of a problem when mortgage interest rates are very low, as consumers’ purchasing power is boosted. But rates won’t stay this low forever.

And as interest rates rise, this affordability problem will become more apparent in a handful of hot markets where home values are already at or near their prior peak levels, such as San Jose, California. Home values there rose 24% in August. Because rates are so low, San Jose homeowners currently spend 34% of their monthly incomes on a mortgage. But looking ahead, even assuming appreciation at a slower 8.3% pace over the next year, once rates hit 5% homeowners will be spending 44% of their incomes on a mortgage—far more than the 36% share they spent in the pre-bubble years between 1985 and 2000.

As a result, in the years to come, home values will have to either stagnate or fall to remain affordable, which we may already be seeing. According to the Census Bureau, existing home sales in the western US fell by roughly 21% in August, even as inventory of such homes rose by 20%. Ultimately, consumers in the western US bought fewer homes not because they couldn’t find any to buy, but because they didn’t want to pay the price.

It’s clear that moderation is happening, and has to happen. But what’s less clear is when the Federal Reserve will take its foot off the gas and allow moderation to occur more naturally.

The Fed recently delayed plans to begin drawing down its monthly purchases of Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, which is helping to keep mortgage interest rates incredibly low. This tapering activity was expected to begin as early as September.

The Fed knows its actions move markets, often dramatically. But so do political debates, particularly of the sort currently being waged over the federal budget and debt ceiling. It seems likely the Fed has stepped back from its tapering plans at least in part to avoid hitting the economy with a one-two punch of politically induced budget blows to the body and an uppercut of tightening monetary policy.

The Fed needs to throttle-back its stimulus sooner or later, especially as it relates to the housing sector. But fearful of too much moderation introduced by political wrangling, the Fed may feel it has no choice but to stay the course for now, essentially playing the role of responsible adult. So we’re left not knowing what will happen in the political arena, and not knowing when the Fed will remove itself from the market.

In the end, this uncertainty may help foster volatility in the market. Some markets run a real risk of overheating as rates remain low. Other markets will remain real bargains even with higher rates because prices have fallen so far. Couple this with persistently high levels of negative equity nationwide, which will continue to restrict inventory and dampen demand as underwater homeowners remain stuck, and localized volatility will be the buzzword through at least the end of the decade.

The housing market today is undoubtedly in a much better place than it was in the recent past. Assuming the broader economy continues to recover more slowly, housing demand should continue to slowly increase, which will have a stabilizing effect even while rates rise. But it’s critical that we understand how the political choices we make today will have considerable economic impacts, particularly on the housing market, tomorrow.