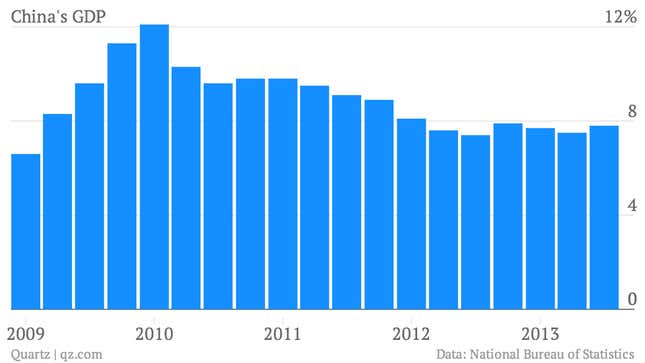

After two surprisingly dismal quarters, China is finally back, posting GDP growth of 7.8% for the third quarter, compared with Q3 2012. That’s way higher than the 7.7% that most expected thanks to a flood of government spending, and up from Q2’s grim 7.5%, the lowest growth since the financial crisis. Here’s a look at the trend:

China is the only major economy to set a target GDP rate, and the new figures put the country well on its way to clear the government’s all-important 7.5% threshold for the full year. With China growing 7.7% cumulatively in the first three quarters, it would have to crash big-time in the fourth quarter to miss that target.

But is it safe to call this a return to form?

It depends on meaning of “form.” If you mean unstoppable economic engine that leaves all other emerging markets in the dust, then maybe. If you’re talking about growth dependent on government support and cheap bank loans, then definitely.

From January to June, investment in transportation—things like overpasses and railway tracks—grew 21.5% on the previous year. Something goosed that a lot in the third quarter: in the nine months ended in September, transportation investment leapt 40.6% on the same period the previous year. Other things soared even more, such as water conservancy (up 52.2%), which includes investments in sewer systems and the lik.

This investment obviously had a lot to do with the stimulus-in-all-but-name that the government set into motion early in the quarter. That was around the time it became clear that there wasn’t much in the way of organic growth to prevent the economy from sputtering.

The headline 7.8% growth figure, therefore, owes more to the government’s fiscal pump-priming than to genuine growth driven by genuine demand.

And that’s just China’s problem. Withered global consumption and the fact that governments around the world are increasingly shoring up their own industries means that China’s once-reliable export market isn’t so reliable anymore. That’s not just a problem for exports, which drive less and less of China’s growth. The lack of domestic demand—only 36% of China’s GDP comes from consumption—and a drop in demand from the rest of the world will eventually make China’s wasted investment and overcapacity grow more and more apparent, as they started to earlier this year.

Those signs of waste could emerge as soon as this quarter. That is, of course, unless Chinese consumption finally starts to grow. Then we’ll see a strong fourth quarter that isn’t inflated by government spending and cheap bank loans.