At first glance it seems China’s economy is back on track. After some promising signs in the last two months, today’s slew of economic data brought the biggie. Industrial production in August grew 10.4% year-on-year, a 16-month high. Investment in fixed assets—things like factories and infrastructure—soared as well, and retail sales jumped too.

What’s behind this turnaround? For one, we have premier Li Keqiang’s “mini-stimulus” (paywall), which slashed taxes on smaller companies, cut administrative costs for exporters and created new financing channels for investment in China’s railways. In late July, the government also upped infrastructure spending targets to 1 trillion yuan ($163 billion) (paywall); beneficiaries include a tunnel under the Bohai Strait, new subways and a slew of city and provincial projects (paywall).

Li seems to be good on his word. Production of steel, which is used to make things like subways and huge undersea tunnels, leapt in August even as housing development—usually a big driver of demand for industrial goods—slowed. And research analysts are revising their estimates for China’s 2013 economic growth.

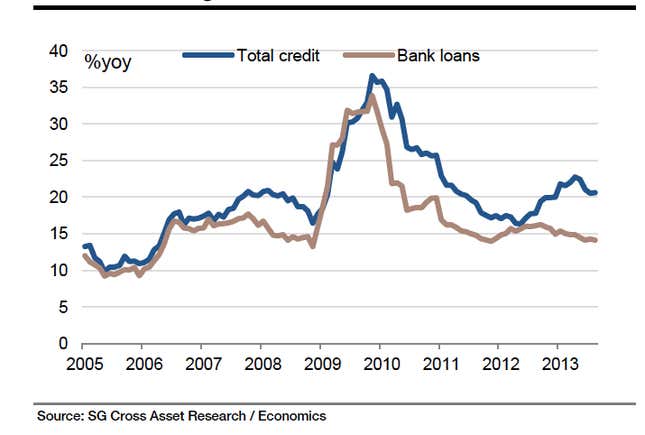

The next question, though, is whether this is really a sustainable recovery. There is at least one sign that it’s not: growth appears still to be financed by dubious means. As Société Générale’s Wei Yao notes, shadow lending surged in August. That’s when banks lend through channels that aren’t recorded on their balance sheets, typically to projects too risky to qualify for official loans. They are doing this because Li has been pressuring them to rein in official lending but they still need to drum up income somehow. As you can see, the growth rate in bank loans has fallen over the past year but that of total credit has (mostly) risen—implying a lean towards shadow lending:

That lending gush, says Yao, could sustain a recovery for a bit longer, but will leave Chinese companies and local governments even more dangerously deep in debt than they already were.