Even for someone who did not know Anthony Bourdain, who saw his shows only sporadically and did not own a copy of Kitchen Confidential, the internet was a raw and painful place the day the acclaimed chef and storyteller died by suicide. It wasn’t just the loss, but the intentionality of it, and its happening just three days after designer Kate Spade’s death by the same cause only amplified the sorry senselessness of both.

Eventually, I turned it off, all of the obituaries, tweets, and pieces about mental health. But there are some channels that can’t be shut down easily, and it ate at me: not why these two individuals died in this way, which is unknowable, but why anyone does, and what invisible hand pushes some people in crisis closer to the precipice and holds others back.

I thought about what a selfish, abusive parasite depression is. I thought about the ghastly pain that deaths by suicide leave behind.

Most of all I thought about that hotline number offered up in the wake of suicides. I thought about why, for some people, a stranger’s disembodied voice cuts through the internal din of depression in a way that the voices of their most beloved friends and family cannot. I wondered why this phone number saves people, and I marveled at how lucky I was that it once saved me.

Get your facts straight

In 2016, I was pregnant with my second child. My husband and I had just moved the family back from London, where we’d lived for several years, and were staying with relatives in California while we worked out our next move. I was a few months into a new job at Quartz and spent my days shuttling a bubbly girl to preschool, catching up with family we hadn’t seen in a while, and chatting online with friendly, welcoming colleagues in New York.

It was a stressful time, but not significantly worse than anything you and the people you know have likely experienced. Clinical depression is not “caused” by difficult events. Difficult events create stress, and in some brains—thanks to a complicated cocktail of genetics, neurochemistry, family history, and personal traits that no one yet fully understands—that stress triggers depression.

Depression was something I had dealt with quietly and privately since my first experience with it as a teenager: regular medication, periodic checks with a therapist, disclosures only to immediate family and a few close friends.

This is not itself wrong. It is entirely acceptable to share your personal health concerns with only a trusted few. But it also meant that my default response to the illness was to invent reasons to work from home, decline social invitations, and otherwise retreat until the feelings passed. These weren’t therapeutic decisions. I was ashamed of having depression, and decisions made purely out of shame rarely turn out to be in anyone’s best interest.

Pregnancy also is a precarious time for a person with pre-existing health concerns, mental health included. Prior to this pregnancy, I’d read the reports of an inconclusive but much-publicized study linking antidepressant use in pregnancy with autism.

I did not read them well. I saw the finding that babies exposed to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors—SSRIs, a common class of antidepressants—in the second and third trimesters were 87% more likely to develop autism than children whose mothers didn’t take the drugs. I forgot that correlation is not causation. I didn’t notice that it was unclear whether children’s autism was linked to the drugs, or to the depression itself, or to neither. I didn’t process how low the absolute risk of a neurodivergent diagnosis was, or that 98.8% of the babies born even to women who took the medication did not have autism.

What I took away, instead, was a deeply flawed conclusion based on guilt instead of science: Mothers who take antidepressants endanger their babies’ health.

I informed my new obstetrician that I would wean off the medication. She was a bit skeptical, but didn’t challenge me. She was an experienced and thoughtful doctor, yet I can’t imagine she’d have been as permissive had I announced my intention to discontinue treatment for diabetes or asthma. Over nine months and countless checks of weight, blood sugar, urine protein, blood pressure, fundal height, and heartbeat, neither the doctor nor I ever seemed to consider that abruptly stopping treatment for a known chronic condition—depression—might pose a threat to the baby, or to me.

The sluggishness that soon settled into my brain felt like just another of the inconveniences that good expectant mothers endure for their child’s well-being, like swollen feet or skipping sushi. Then, mid-way through the pregnancy, during an especially difficult period of uncertainty over where we would live and work, something shifted. The usual fog of depression consolidated into something darker.

Be honest

A curious friend once asked what depression feels like, and the best I can offer is that it’s like a musty shag carpet wrapped around your brain. It muffles all the comforting and inspiring and encouraging sounds from the outside; it creates this stifling dark space in which you are alone with your own thoughts, which are ugly, and mean.

And it’s boring. Oh, my God, depression is so boring. It’s the same gray wash over everything, the same tired, defeated monologue playing constantly in your ear. It settles into a body like a virus or bacteria, but its advantage over staphylococcus is its ability to convince its host that it’s not an illness at all. That the dark thoughts it produces are realizations of fact, and not the symptom of a treatable condition.

Here is everything I had at my disposal at that time: A caring spouse. A network of loving friends and extended family scattered around the world, such that there was someone awake at literally any time of the day or night to talk, if I’d been so inclined. I had health insurance, and access to medical care, and a competent and concerned physician who may have neglected to ask some questions but would almost certainly have responded had I been honest about the thoughts I was having.

And as you might remember: I have kids. Kids I love very much, who alone were a convincing argument for why my presence was necessary. I felt guilty if my daughter was the last one at preschool to be picked up, yet, at the same time, a narrative unspooling in my brain insisted she might somehow be better off if I never picked her up again.

To see a parent’s death by suicide as a deliberate act of indifference or malice toward a child “assumes the parent believes his presence on this earth is a boon to the child, a benefit rather than a burden,” author Sara Benincasa wrote recently. “This assumes the parent is thinking logically and clearly and calmly. This assumes the parent is not also a person who has to live every moment inside the torture chamber of an unquiet mind.”

One honest conversation with any of the adults mentioned above could have saved all of us a lot of trouble later. But I didn’t tell anyone. Instead, I went through the motions of being a mother, a wife, a friend, a professional. I said I was fine when I wasn’t. I went to work every day and replied with cheerful emojis on Slack, and made pleasant chit-chat with the parents at the preschool concerts. I continued to post bullshit on social media implying that since my ability to appreciate a nice sunset was intact, so was everything else. I did not want anyone to know how badly I was struggling.

The fact that I was deliberately misleading the people closest to me, precisely so that they wouldn’t understand the depth of this illness, is why the well-meaning entreaties to just “reach out” across the void of depression miss the point. I don’t think there are many people who are aware that a loved one is depressed to the point of contemplating suicide, but just haven’t gotten around to “reaching out” yet.

I knew there were numbers for people to call when they were thinking about suicide, but to be completely honest, I thought they were for people who didn’t have anyone else to talk to: people rejected by families that should have cared for them, or who had no access to professional counseling services. I had all those things, I reasoned, and so many other privileges that many more deserving people lacked—so in this case, the problem must be on my end.

Then one morning, I woke up with the low rolling pains that signaled that labor was starting. It didn’t feel like a baby was ready to come from my body; it felt like he was on his way from somewhere else to this broken place—unless I did the right thing. There was no more time to wait. It was time to act.

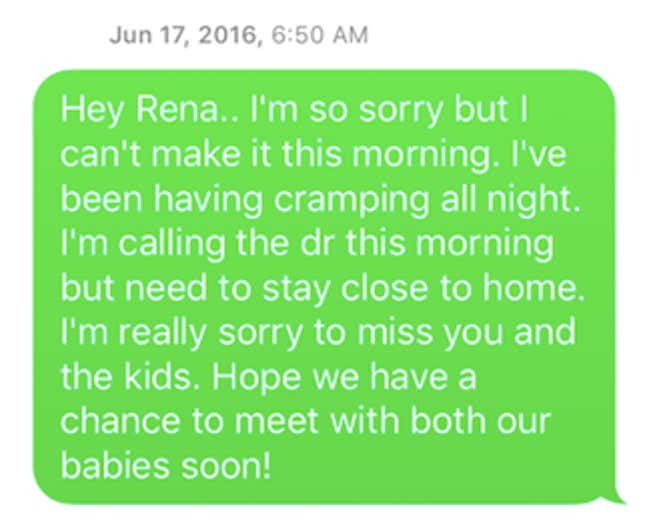

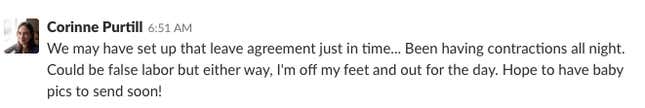

I messaged the cousin I was supposed to meet for lunch, and sent her this:

I messaged my editor, a kind and empathetic person who was a dogged advocate for my maternity leave, and sent her this:

To my husband, my parents, my children, I sent nothing at all.

Had I done what I thought I wanted to do that morning, they all would have gone back to look at what they saw, or didn’t see, in our last exchanges. They would have looked for something they missed, a sign that they could have done something differently. And there’s nothing. There’s nothing there.

Pick up the phone

I dropped my daughter off at school. I know that because I read it in the doctor’s notes later. I have no memory of it.

I drove to the parking lot of a strip mall and parked my car under a tree. In the strip mall was a store that sold something I intended to buy. I intended to buy this thing and use it, and that would be that. I’m intentionally vague here because it isn’t helpful, in writing about suicide, to dwell upon the particulars of how people harm, or plan to harm, themselves.

I went into the store and looked at the variety of things on their shelves and felt my heart plummet, because I knew then I wasn’t going to do what I’d planned to do, and didn’t know what to do instead.

I went back to the car a mess. A crazy mess, all tears and snot. It was the worst place I have ever been.

I didn’t want to call anyone. I had to call someone. It was no longer possible to find a way out without telling someone I was lost. There was battery left in the phone. I Googled. I stared at the number, this lifeline that in another state, another lifetime, I could never have imagined reaching for. And I called.

I was put on hold. That is a thing that happens, because the lifeline isn’t just one line, but a network that connects callers to one of 150 crisis centers around the US, and sometimes it takes a few moments to reach an available operator. I stayed on the line because even the crackle on the line was more comforting than the emptiness of the car, and because I was very clearly out of better ideas. And then someone picked up.

If he gave me his name, I don’t remember what it was. I remember that he had what sounded like a younger male voice, with a slight Southern drawl.

He introduced himself. Then he paused, and waited for me to speak, and in his silence there was kindness and compassion. I still didn’t have the strength to look someone in the eye and admit how I was feeling. It was all right. I didn’t have to. I was no longer alone.

I asked him what to do; he told me to go to the hospital. I asked what I should say at the hospital to explain this thing I couldn’t explain to myself. He told me to say that I was having a “psychological emergency.” That helped enormously. This thing had a name. It was not so monstrous that it could not be bound by language.

From the parking lot, like a detail in a story that an editor would excise as unbelievable, I could see the tall building where I was supposed to have my baby. And because a stranger at the end of the phone listened and spoke to me like a person deserving of dignity and patience, I pulled out of the strip mall and drove there.

I went to the desk you have to go to when you’re having a baby, and said what the man on the phone had told me to say. And from that point until I held my son in my arms, every nurse and doctor I encountered treated me with compassion. My doctor called my family and helped me to understand that I wasn’t damaged person, but an ill one, and that ill people can get better.

There are parts of the story of how my son came into the world that aren’t easy to talk about: how the nurse searched my purse and locked it away, apologetically, lest I find something in it to harm myself. How an attendant sat in my room 24 hours a day until I was discharged, even as I slept. The interview with the man whose signature made the difference between going home to my family and being indefinitely committed to whatever place the state provides to people with broken minds.

But at some point, during the blissful calm of the epidural, something fell back into place. I wanted to be present for my daughter and for my son, whose presence became real in a way the disease had never allowed me to understand up to that point. I wanted to feel the richness of the life I already had. I wanted to live.

“Never kill yourself while you are suicidal”

Soon after Anthony Bourdain’s death, Frank Bruni wrote in the New York Times that it was a “puzzle” that none of the evident riches of Bourdain’s life—not his beloved child or partner, nor his satisfying work—could “buoy” him during his depression. It did not seem a puzzle to me. Depression doesn’t correspond to the normal laws of physics. It doesn’t operate from the same set of facts. To act as if it does is a profound disservice to the survivors of a loved one’s suicide. There is no direct relationship between how much a person has to live for and the severity of their disease.

I had a lot of advantages walking into that hospital. Had I been a mother of color, a teenage mother, or a mother without health insurance, it’s less likely that I would have received adequate mental health care at any random hospital in the US.

Because that is what depression is: It’s an illness that can be treated like any other, that is better managed with preventive measures and early interventions than by emergency responses to late-stage crises. One of depression’s most unfortunate symptoms is that it convinces its sufferers that it’s not a disease they have, but a fundamental problem with who they are. Treatment is not always easy, but it’s possible. This condition does not have to be a terminal one.

Recovery took time. I wasn’t allowed to leave the hospital without proof of appointments with the therapist I should have called months before, and with a psychiatrist who would ensure I had the medication I needed. I kept all of the appointments, as dutifully as I kept to the schedule of pediatric check-ups and vaccinations for my son. A family is an ecosystem, and I now understand that all of its members—even parents, even moms—need to be cared for if the others are to thrive.

I was lucky. Not everyone gets another chance.

There are different theories for why people with depression decide to end their lives. The late Edwin S. Shneidman, a psychologist and groundbreaking researcher on suicide, theorized that people end their lives to escape psychological pain that has become to them intolerable. Florida State University psychologist and Why People Die By Suicide author Thomas Joiner agrees, adding that people who die this way typically exhibit three key characteristics: a low sense of belonging, a heightened sense of burdensomeness, and an acquired capacity for self-harm.

This doesn’t mean that people with such tendencies are in any sense fated to die by suicide. There are 16.2 million adults in the US who had a major depressive episode in the last year; the vast majority, fortunately, will not act to end their lives. But why some individuals who reach the point of suicidal depression take that last irreversible step, and others reach for a lifeline just in time—that, no one knows.

“Why anyone kills himself or herself at a specific time is better not asked; it is tricky, enigmatic, and futile,” psychiatrist Avery Weisman wrote at the age of 90, after treating countless patients with depression. Data scientists have created a machine-learning algorithm that can predict a given patient’s risk of suicide more accurately than human clinicians can, but the machines can’t tell us why people do this thing that defies logic.

“It is simply good sense not to commit an irrevocable suicide during a transient perturbation in the mind,” Schneidman wrote in his book The Suicidal Mind. “Never kill yourself while you are suicidal.” He continued:

Every single instance of suicide is an action by the dictator or emperor of your mind. But in every case of suicide, the person is getting bad advice from a part of that mind, the inner chamber of councilors, who are temporarily in a panicked state and in no position to serve the person’s best long-range interests. Then it is time to reach outside your own imperial head and seek more qualified and measured advice from other voices who, out of their loyalty to your larger social self, will throw in on the side of life.

I continue to regularly consult those more qualified and measured voices, because I understand now that depression unchecked can harm me and those I love, and so I have a responsibility to do all that is in my power to treat it. If I knew I had a condition that causes seizures or blackouts, I could not ethically get behind the wheel of a car untreated. The same is true of mental health. It’s a paradox: a commitment to take responsibility for one’s own health and survival, while acknowledging that means reaching out for help in the times when it’s necessary.

People end their lives to end pain, but suicide doesn’t end suffering. It just shatters it and disperses the shards to heartbroken survivors. The only way to safely dispose of pain is to transform it into something different, something of enduring value: into art, or empathy, or resilience.

Get on the scale

Some things we keep quiet because we’re ashamed, and others we keep quiet because they are private, and live best in the intimate space between us and the people we trust the most. For a long while, that’s where I preferred to keep this story. But then I realized that if no one ever talks about healing from a mental health crisis, no one will ever know that a low point doesn’t have to be a final one. If no one ever talks about the mental state that precedes suicidal actions, being in that state feels all the more isolating, and survivors’ lingering questions all the more painful.

What if there were stories of people having heart attacks but none about surviving one? What if we talked about people being diagnosed from cancer, but never discussed the possibility of remission? How much easier it would be to assume that once you’ve stepped over a certain line, there is no coming back. To know otherwise and refuse to share it feels irresponsible.

World Suicide Prevention Day is this week (Sept. 10). So in its honor, here is one story shared as another scrap of evidence of the good that comes from asking for help. And it’s a message of heartfelt thanks to the people who do the important and necessary work of picking up the phone and talking to people who are calling in their lowest, most painful moments. It’s a note of deep gratitude to the person who picked up the phone for me.

Much has changed in the two years since. My depression isn’t cured: statistically, a person who has experienced multiple bouts of severe depression is likely to have one again. But I understand it better, and understanding improves any relationship, be it with a partner, an enemy, or the particulars of one’s own neurochemistry.

One of the most important things I’ve learned is that the most effective defenses against depression happen long before it reaches the emergency stage. You can’t take care of your mental health only when it’s gotten so bad you can’t take care of anything else. It can be hard to sacrifice the time or effort for maintenance without the pressure of a crisis, but it’s necessary. That’s what mental health care is, and why a system that acknowledges catastrophes but not prevention is a broken one.

An excellent cognitive-behavioral therapist gave me the single most helpful non-medical tool I’ve found in two decades of dealing with depression. It’s a scale, with one being a spectacular day, and 10 being sobbing in one’s car to a stranger on the suicide hotline. Together we wrote down concrete steps I have to take as soon as I feel myself sliding from three, to four, to five. When I feel a change in my mood now, I do these steps. I do them obediently, like a person who has been tasked with the care of a complicated machine or a fragile seedling they don’t fully understand but really don’t want to screw up.

I tell my husband what’s going on, because depression thrives in isolation. I exercise, because exercise releases endorphins, and I meditate, because it’s calming and helps me remember what I’m supposed to do next. Then I call another person I trust to share what’s going on, as a pre-emptive strike against isolation. This person is often a particularly understanding aunt. I ignore the anxious voice that insists that I am wasting her time, or have nothing to say, or should be able to handle this alone, and I call.

I say, “I’m doing my steps,” and she understands. And then she just sits with me on the phone, in that compassionate silence where things are healed.

The US National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is (800) 273-8255. If you need them, call them. They’ll help.