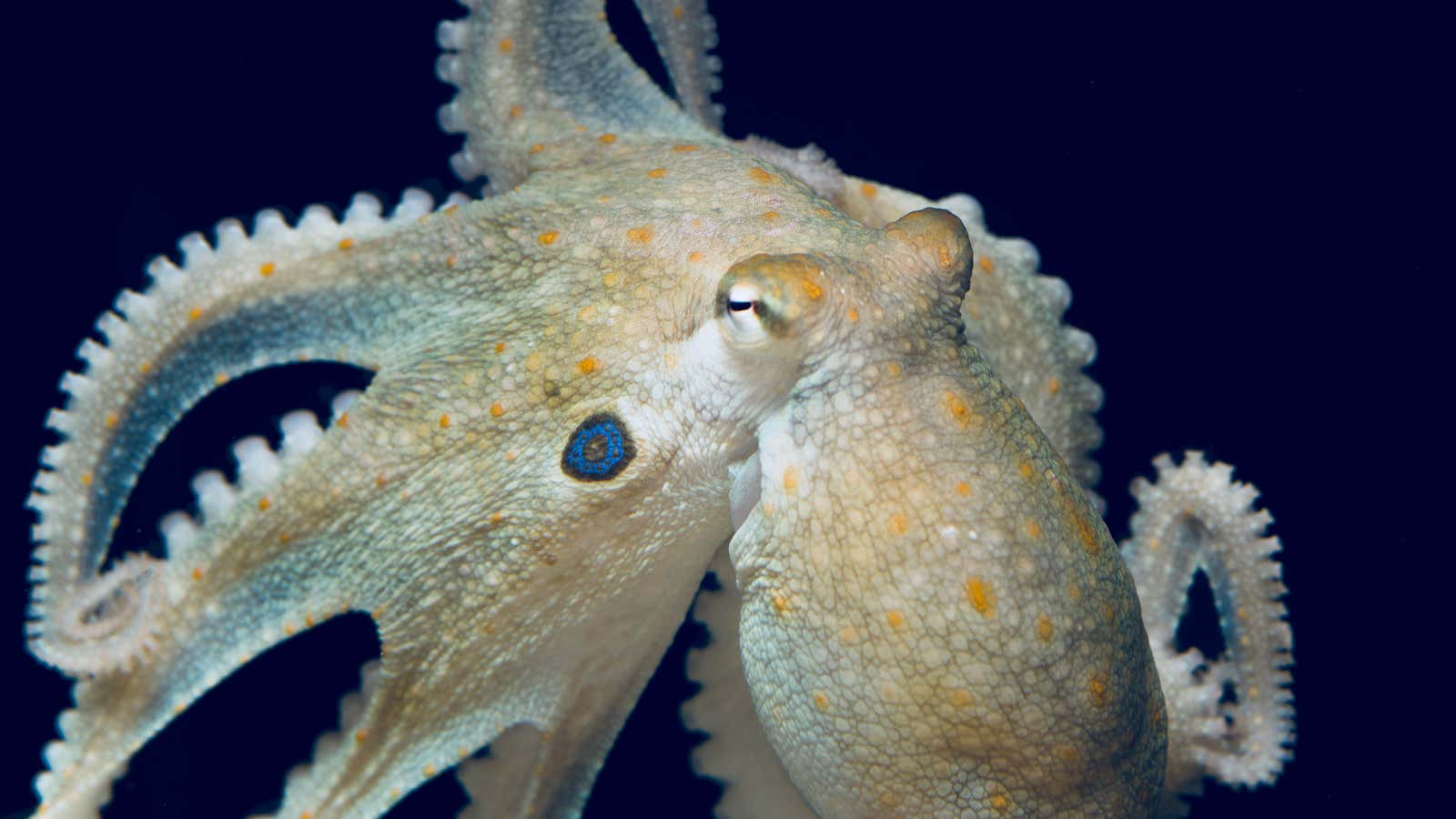

You might not imagine humans have got a lot in common with octopuses. The bizarre, clever, gelatinous, shape-shifting creatures, with eight tentacles, three hearts, blue blood, and the ability to change colors and taste with their skin seem as close to space aliens as anything on Earth.

Soak the solitary sea dwellers in a bath of the drug ecstasy and our commonalities become more apparent, according to new research published in the journal Current Biology today (Sept. 20). Even these loners become more friendly and social when exposed to MDMA. That means, evolutionarily speaking, we share more qualities with the octopus than was previously thought, say neuroscientists from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“The brains of octopuses are more similar to those of snails than humans, but our studies add to evidence that they can exhibit some of the same behaviors that we can,” lead investigator Gül Dölen explains in a statement. “What our studies suggest is that certain brain chemicals, or neurotransmitters, that send signals between neurons required for these social behaviors are evolutionarily conserved.”

Dölen and his team were interested in the effects of ecstasy on octopuses because it’s obvious the creatures are smart and conscious. The solitary cephalopods trick prey to come into their clutches, appear to learn by observation and have episodic memory, the researcher says. They are known for escapes from tanks, playing pranks, eluding caretakers, and seem even to have a sense of humor.

Dölen and Eric Edsinger, a research fellow at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, studied the genomic sequence of Octopus bimaculoides, commonly referred to as the California two-spot octopus. They found startling similarities between octopuses and humans. We have nearly identical genomic codes for the transporter that binds the neurotransmitter serotonin—a mood regulator—to the neuron’s membrane.

Serotonin is associated with mood and linked to depression. In the human brain, MDMA binds to cells that transport serotonin, and that’s why taking ecstasy alters mood and tends to make people feel, well, ecstatic, and more inclined toward their fellow humans. Experiments with mice and MDMA have also shown similar effects, making the mice more social.

Eight arms to hold you

Given the newfound similarities between the genetic codes of octopuses and humans then, the researchers wondered what would happen to loner octopuses exposed to MDMA. Would they too become more social?

The answer, it seems, is yes. Four octopuses, two male and two female, were soaked in water with liquefied MDMA for ten minutes—the creatures absorbed the drug through their gills. Then they were placed in experimental chambers, a series of three connected tanks. One was empty, one chamber had a plastic action figure under a cage, and one had an octopus under a cage. The octopuses on ecstasy were placed in the experimental chambers for 30 minutes and showed a remarkable attraction to the tank with a caged octopus.

Despite their usually solitary behavior, all four of the creatures on ecstasy were attracted to the chamber with a fellow octopus. They spent more time there than the other two chambers, researchers say, and seemed to really want to hang out. “It’s not just quantitatively more time, but qualitative. They tended to hug the cage and put their mouth parts on the cage,” Dölen explains. “This is very similar to how humans react to MDMA; they touch each other frequently.”

But when the same experiments were conducted with the same creatures minus the MDMA, they showed little interest in the other octopus nearby, choosing the empty chamber instead. The researchers believe this suggests that the brain circuits guiding social behavior in octopuses aren’t so different from ours but are mostly suppressed except when mating, and that a more social effect can be influenced by the use of ecstasy.

Not yet a model that sticks

If the underlying circuitry guiding their social behavior is actually similar to ours, then octopus research could illuminate the human brain, too, providing guidance on evolution and the use of ecstasy as a tool for treating psychiatric disorders. Dölen cautions, however, that the results are preliminary and need to be replicated and affirmed in further experiments before octopuses might be used as models for brain research.

Notably, the MDMA used in the experiment was a gift from Rick Doblin, founder of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. MAPS is studying MDMA for potential treatment of post traumatic stress disorder and the FDA in January granted special “breakthrough” status for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD, which has entered phase-3 trials.

Cephalopods generally, and octopuses specifically, have been used for neuroscience research for the past century, and now—because they’re now known to be clever and conscious—they have special protections, unlike other invertebrates. In 2013, the European Union granted them the same protections as vertebrates. The UK, Canada, New Zealand and some Australian states also have special rules for experimentation on these creatures who are known to feel pain in order to guard them, ensuring humane treatment.

The study using ecstasy does raise interesting ethical questions. Is it OK to dose an animal with drugs just so we know how they respond? The researchers did not address Quartz’s question when asked about it, sending a general statement on their experiment instead. Based on the published results, however, it appears that the octopuses on ecstasy didn’t suffer excessively and may even have had a pretty good time.