Since it suffered its own real estate boom, bust and financial crisis in the early 1990s, Japan has spent the better part of two decades clawing out of deflationary quicksand. (While deflation—a broad-based decline in price levels—might sound good to those struggling with high living costs, it’s a very bad thing for an advanced economy, acting as a persistent headwind against investment, consumption and growth.)

Recently, a concerted push of monetary and fiscal stimulus from Japanese officials—known as Abenomics—suggests that Japan could finally be breaking the deflationary cycle. Price levels have turned up markedly in recent months. For the global economy, that’s a good thing; a strong and vibrant Japan—still the world’s third-largest national economy—would provide another leg for the global economy to stand on.

Unfortunately, just as Japan approaches escape velocity from the deflationary vortex, Europe is showing signs of what could be long-term economic trouble for the world economy. (The 27-nation European Union is the world’s largest economic bloc.) The latest update on price levels in the euro zone today showed headline consumer prices rising a piddling 0.7% in October, from the same month in 2012. That was much lower than economists had expected. Core inflation—which strips out the noisy and volatile prices of products like food and energy—rose just 0.8% compared to last year. That’s a record low.

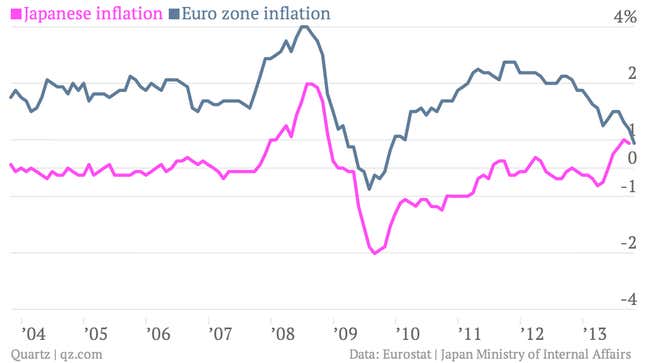

The bottom line? Europe is playing a serious game of footsie with deflation, just as Japanese prices have finally stopped falling. Year-on-year price changes actually increased 0.7% for Japan in September. This chart shows the deflation baton being handed off to Europe.

As Japan’s experience has shown, once you slip into deflation, it can be very, very hard to get out. The traditional tools of central bankers are much more effective at quelling inflation—just raise rates until the economy cools off—than generating it. (A central bank can print money, but that doesn’t mean that it’s going to circulate around the economy, which is what creates needed growth.)

For its part, the European Central Bank isn’t even attempting to confront the problem. In fact, the ECB is actually tightening monetary policy right now, albeit in a somewhat stealth way. That’s the mistake that the US Federal Reserve made at the start of the Great Depression. And it bodes particularly poorly for a European economy that only just wobbled out of recession itself. So will this lead to another crisis? No. But deflation could damage Europe’s economy for decades, and that’s bad news for everyone.