For over 100 years, Alzheimer’s disease has stumped neuroscientists. Although they understand that the deadly form of progressive dementia is often characterized by buildups of misshapen proteins in the brain, what causes these malformations has remained elusive. There are several theories, ranging from air pollution and diet to genetics and vascular disease, but none have been confirmed (except for a small portion of the population with an inherited mutation that causes them to develop early-onset Alzheimer’s). One other theory that has traditionally been fairly fringe but is starting to gain headway connects Alzheimer’s to a handful of prevalent viruses.

Last week, Ruth Itzhaki, an emeritus professor of molecular neurology at the University of Manchester, published a review of new work linking dementia to the viruses that cause herpes. Specifically, these studies focused on HSV1 and HSV2, which can cause cold sores on the lips or genitals, and herpes zoster, which causes chickenpox during childhood and shingles later in life.

All three of these viruses are common but largely benign. Some estimates suggest that virtually all adults have been infected with herpes zoster, and almost 80% of people globally are infected with HSV1 or HSV2 at some point in their lifetimes. Most people pick up these viruses as children and temporarily develop visible symptoms like pox or sores, but the viruses then usually go dormant—and so don’t cause symptoms—for the rest of their lives.

In this review, Izhaki highlights three papers studying thousands of patients living in Taiwan (where health records are available for nearly the entire population) and their likelihood of developing dementia. (Alzheimer’s makes up the majority cases of dementia, but was not isolated specifically in these studies.)

Two of these papers compared groups of people diagnosed with herpes zoster to groups of people who did not have the virus. It found a slight increase in the number of cases of dementia in those with herpes zoster.

A third study looked at over 8,000 who visited the hospital at least three times in a year for the treatment of cold sores—a signal that they had severe cases of HSV1 or HSV2—and compared to a control group of about 25,000 people. Those with cold sores were more than twice as likely to develop dementia. Further, of the patients with cold sores, those who received antiviral medications were far less likely to develop dementia compared to those who did not.

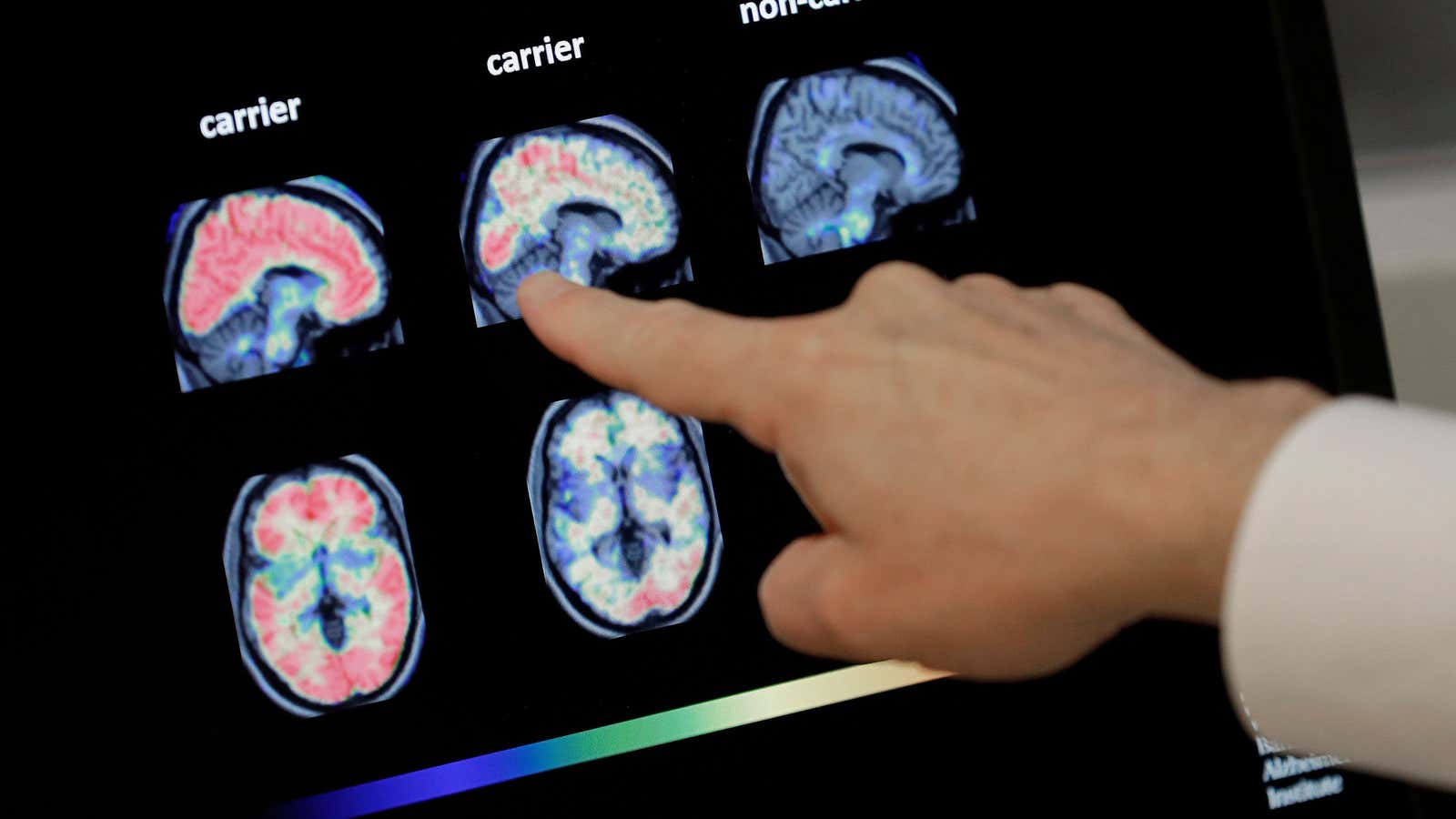

Itzhaki has been studying the link between Alzheimer’s and herpes viruses for decades. Her team’s previous work has found that in petri dishes, HSV1 can cause brain cells to produce toxic proteins like amyloid beta and tau, both of which have been specifically associated with Alzheimer’s disease. There’s other evidence for the connection: people with Alzheimer’s disease who also have a variation of a gene called APOE type-4 have a higher risk of herpes infection. This same variant of APOE has also been documented to elevate the risk for Alzheimer’s in general, although it’s not clear exactly how. Itzhaki believes that in individuals with APOE type-4, the combination of the direct damage from a virus replicating and indirect damage from the resulting inflammation is what eventually leads to Alzheimer’s.

The immunologist Leslie Norins explains that whatever causes Alzheimer’s might not be like the kind of infection we normally think of, like a cold or flu, both of which are highly contagious. Instead, it may be something that can be passed on only after prolonged exposure, or an infection that is benign in most cases, but turns deadly in people with certain genetic traits. (Norins in 2017 created the Alzheimer’s Germ Quest, an organization that promises $1 million to anyone who can prove that Alzheimer’s is linked to any kind of infection.)

There’s precedent for thinking that Alzheimer’s could be infectious. Earlier this year, another study showed that two different strains of the herpes virus—HHV 6A and 7—were present in high quantities in patients who died of Alzheimer’s. Other scientists have suspected that bacteria similar to the ones that cause Lyme or syphilis or lung infections (paywall) may also play a role in causing the disease to develop years after infection. And previous work has shown that both neurosurgeons and spouses of people with Alzheimer’s have higher risks of developing the disease than the general population.

Not all scientists are convinced of the Alzheimer’s virus hypothesis. “Dementia is not contagious and shouldn’t be thought of as an infectious disease,” James Pickett the head Head of Research at Alzheimer’s Society, said in a statement. James Hendrix, the director of global science initiatives at the Alzheimer’s Association, told MedScape (free login required), “We don’t have enough direct evidence to even go there yet.”

Norins argues that based on what we see in epidemiological studies, we could take action even without knowing for sure what causes Alzheimer’s. For example, since it seems patients treated with antivirals for HSV1 and HSV2 have a lower risk of developing dementia, Norins says, let’s use those antivirals more liberally for those with either of those viruses.

Proving Alzheimer’s is caused by a viral infection would require showing that large populations that were protected from herpes viruses did not develop the brain disease later in life. However, that kind of study would require a literal lifetime of following participants, from childhood through death. Even if a team had the resources to do such a long-term study today, however, they’d first need to develop a vaccine for some viral strains. Although there is a vaccine for herpes zoster now, there are still none for HSV1 or HSV2—ironically in part because they are considered to be fairly benign viruses.