On a frigidly cold night in February 2017, hundreds of near-rabid people pushed and pummeled their way to a warehouse entrance in New York’s Financial District.

Welcome to our field guide on luxury and fashion. Check out other parts of our deep dive here.

The well-dressed and well-to-do were clamoring to make their way inside one of New York Fashion Week’s biggest parties, the F is for Fendi event that promised celebrity appearances (and an open bar, of course), but instead turned into an unmanageable riot outside the venue as crowds overturned barriers and tried to push past Nimitz-class bouncers. Inside was also pandemonium, as those let in moshed and crowdsurfed while Migos performed on stage with Tyler, The Creator and A$AP Rocky in attendance.

Despite the chaos, the event did what its planners intended. It made headlines. The party characterized a prevailing theme in fashion today: New York Fashion Week (and luxury altogether) isn’t just about runway shows anymore—it’s about extravagant affairs that feed into the hype machine catering to the Instagram generation.

Fashion has always been interested in youth as a culture, but it’s also now chasing youth as a customer. But doing so has put fashion brands and designers into an existential crisis. No one really knows what luxury is anymore. Exquisite craftsmanship? A $900 pair of bulky sneakers? A $1,500 logo-stamped jogging pant? And anyway, is there anyone left to even appreciate “old” luxury?

The target of fashion’s latest obsession is, as is the case with so many other industries, millennials—more specifically, young, affluent, Chinese shoppers eager to get their hands on the latest limited-edition product. While the US still represents the world’s largest luxury market, China and emerging Asian markets are grabbing an ever-greater share of luxury players’ attention.

It means the old guard has to switch things up. Now, the millions shelled out toward advertising in legacy media publications is instead funneled into social media and influencer marketing (on Instagram and beyond); hype-driven product “drops” drive the new sales model; objectively and purposefully ugly shoes are popular.

This ain’t your grandma’s Chanel. Hell, this isn’t even Karl Lagerfeld’s.

The companies behind the brands

Most of the big players in luxury fashion today exist as part of a European conglomerate, taking advantage of the wealth of resources that come with a multi-billion-dollar parent company. But the solar system of fashion extends to venerable independents, new aspirants to the conglomerate echelon, and a group of younger brands that are challenging traditions.

The ruler

LVMH

Brands: Louis Vuitton, Fendi, Emilio Pucci, Loewe, Marc Jacobs, Celine, Kenzo, Dior

Revenue (2017): $48.65 billion

CEO: Bernard Arnault

The Paris-based conglomerate headed up by the Arnault family is the world’s largest luxury company. In the last 30 years, LVMH has grown to assume ownership of 15 fashion brands you likely already know, and has a stacked bench when it comes to design talent.

The rival

Kering

Brands: Gucci, Bottega Veneta, Saint Laurent, Balenciaga, Brioni, Alexander McQueen

Revenue (2017): $17.67 billion

CEO: Francois Henri-Pinault

There’s no discussing the state of luxury today without mentioning Gucci—which underwent a brand revamp in 2015 at both the financial and creative helms—and is an indisputable winner, bolstering Kering’s bottom line. Alessandro Michele, the Gucci creative director, has spent the last three years creating eccentric collections of vintage-meets-futurist fantasy, with an exploding social media presence and accompanying sales to show for it.

The wannabes

Tapestry

Brands: Coach, Kate Spade, Stuart Weitzman

Revenue: $4.49 billion

CEO: Victor Luis

Capri Holdings Limited

Brands: Michael Kors, Versace

Revenue:$4.4 billion

CEO: John D. Idol

Despite a number of attempts that ultimately failed, there is no American luxury conglomerate to rival the European behemoths. Today, two companies are vying for the title of American luxury heavyweight champion, though it may be too soon to tell yet which will come out on top. Tapestry’s brands currently occupy space further downmarket, while Capri’s Michael Kors and Versace arguably err closer toward true luxury. Ultimately, whichever fashion group can spot the next blockbuster indy brands and snatch them up—all the while maintaining strong performances at the legacy brands—will win.

The independents

Prada Group

Brands: Prada, Miu Miu

Revenue: $3.4 billion

co-CEOs: Miuccia Prada, Patrizio Bertelli

Miuccia Prada, granddaughter to founder Mario Prada, has led the creative direction of the company since launching its fashion business, and embodies the role of fashion guru. To some, she’s the most important woman in luxury since Coco Chanel.

Burberry

Revenue: $3.46 billion

CEO: Marco Gobbetti

After a nearly two-decade tenure as creative head and president at the storied English brand, Christopher Bailey left Burberry in 2018, ushering in a new era of financial and creative leadership. While Marco Gobetti assumed the role of chief executive in 2017, Riccardo Tisci, a popular designer in the industry, would join nearly a year later, an announcement that surprised insiders. Before moving to Burberry, Tisci spent 12 years successfully generating excitement and designing must-have items for French brand Givenchy—one whose aesthetic is dissimilar to Burberry’s heritage codes—all the while cultivating a celebrity and influencer following (Tisci loyalists include the Kardashians.) Today, with Gobbetti as CEO and Tisci as creative director, most are eager to see whether these two will build upon Bailey’s foundation for Burberry’s new era.

Dolce & Gabbana

Revenue (2016): $1.5 billion

CEO: Alfonso Dolce

Despite a select few proclamations of irrelevancy from some within the fashion set, Italians Stefano Gabbana and Domenico Dolce don’t care that they’re politically incorrect, and their fans don’t seem to, either. (They rank 36 out of 100 in Deloitte’s Global Powers of Luxury Goods ranking.) But there’s only so many PR nightmares a brand can handle: The duo is newly under fire for racist ads and Instagram activity targeting Chinese people that forced them to cancel a multi-million dollar fashion show in Shanghai and soured their relationships with countless Chinese influencers and shoppers.

Chanel

Sales:$9.6 billion

CEO: Alain Wertheimer

It’s hard to remember when Karl Lagerfeld started designing for French luxury brand Chanel (it was in 1983) but his tenure is among the longest for any designer in fashion, and one that has proven lucrative.

The disruptors

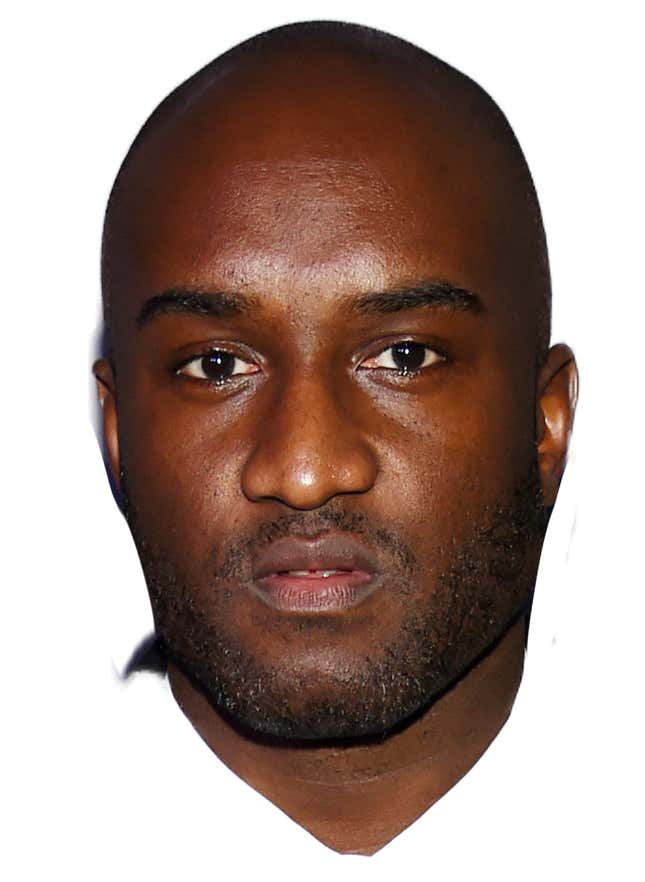

New Guards Group-owned Off-White and its creative director and founder Virgil Abloh (right) have skyrocketed to become one of the hottest brands in fashion. Abloh’s success reached new heights in 2018, when Louis Vuitton appointed the Chicago-native its menswear creative director. (The press—and Instagram community—praised his debut.)

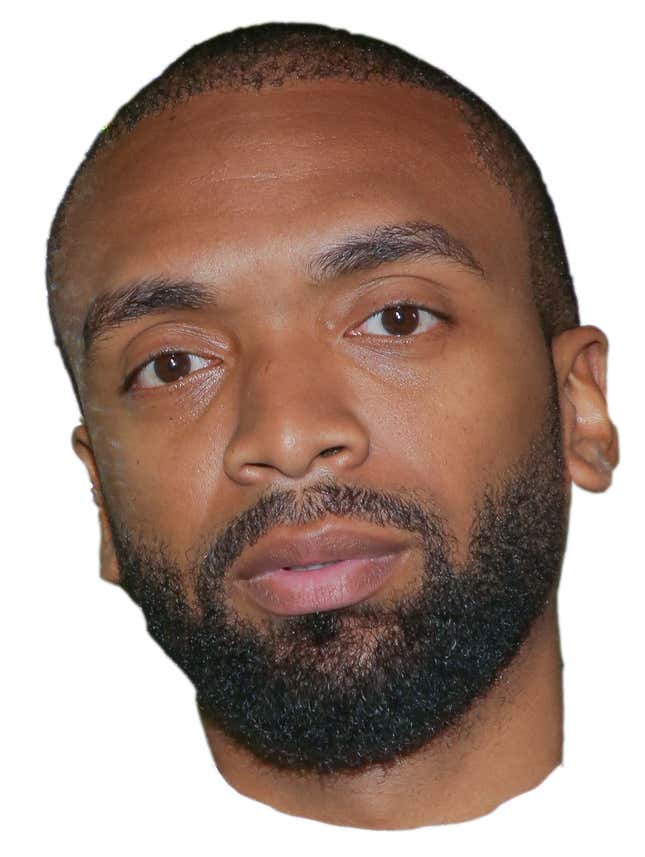

Kerby-Jean Raymond (left) and his brand Pyer Moss went from being a buzzy ticket to among the most important shows at New York Fashion Week. Having recently won the 2018 CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund Award, Raymond is a designer to watch, one whose vision is expected to help the industry become more relevant.

Mike Eckhaus and Zoe Latta (co-founders and designers of Eckhaus Latta) encourage the fashion system to rethink gender norms and beauty conventions in luxury, which has resulted in industry-wide recognition for the brand, including a nomination for the LVMH Prize in 2018.

data point

6-8%: The expected growth of the global personal luxury goods market, to between $316 – $322 billion in 2018, driven by China

What fashion insiders are whispering about…

One perennial topic of gossip? Who’s falling behind:

- There’s been some chatter about how LVMH’s Marc Jacobs has fallen out of fashion (though his most recent runway show was exceedingly beautiful).

- Earnings for Kering’s Bottega Veneta were down yet again in the third quarter of 2018, but with a new creative director comes renewed hope.

- Around 2015, there was crazy hype over an independent brand called Vetements (which is designed by the same man currently designing Balenciaga), but today there are conflicting reports about whether that success has tapered off.

- And there’s speculation that Kanye West’s frequent and polarizing political outbursts have finally impacted sales of his Yeezy sneakers, despite an initial Trump bump.

Name-dropping in hip-hop

Which luxury brands are most popular in music? Data exploring over 4,000 music publishers across 100 countries shows everything’s Gucci.

data point

50%: The share of Gucci revenues accounted for by millennials. Total Gucci brand sales increased by 42% to $7B in 2018.

What happens when a non-streetwear brand attempts a sneaker?

While minimalism and “normcore” dominated the luxury aesthetic in the early 2010s, big, bulky sneakers began to reign supreme by the decade’s midpoint. Since roughly 2015, nearly every brand in luxury fashion has created a sneaker offering, some more successfully than others. Kanye West’s Yeezy Boost 700 Wave Runner sold out quickly when Yeezy released the shoe. Good luck trying to determine whether the Gucci Flashtreks are appropriate evening wear or hiking gear. And if you thought you could get your hands on a pair of Balenciaga Triple S sneakers—the ultimate in ugly dad shoes—you probably couldn’t, considering streetwear bots likely snatched them up before your eyes.

Despite the trend’s seeming ubiquity, not every luxury brand is meant to cater to millennials via sneakers, and some attempts have been notable failures. According to data from Edited, a market researcher, luxury retailers reduced stock of the Versace Medusa high-tops by 70% due to a lack of popularity. And retailers decreased stock of the brown ‘Forever Fendi’ Slingback sneakers, (a “sort of sneaker/Frankenstein hybrid,” says Edited Insights director Katie Smith), by 68% to sell.

QUOTED

“Creative directors are moving around and taking their own personal brands with them. You may have bought into Celine or Saint Laurent three years ago and spent $3,000 on a handbag, and now, the brand direction is completely changed and you don’t feel personally aligned with that brand anymore. Products don’t have any longevity; I wish brands would focus on their own identities and not let themselves be kidnapped by creative directors who’re concerned with their social media following, image, and salary.”

-Biana Kuttikattu, design director at Vince, on the consequences of the designer shuffle

How we got to now

Luxury ready-to-wear fashion made a name for itself after designers like Christian Dior and Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel emerged in the early 20thcentury. By the time Yves Saint Laurent launched his own brand in 1961, ready-to-wear was ready for democratization, a move away from couture and into clothing appropriate for less formal occasions.

Luxury as we understand it today—supermodels and expensive runway shows and celebrity campaigns—materialized in the 80s. (Think The Supers.) It grew through the 90s and into the early aughts, until the global financial crisis in 2008 rocked everything from real estate to fashion. Afterward, luxury executives shifted their focus away from Western shoppers and moved toward a “Chinese shopping frenzy,” as Bain & Co. calls it. Like most industries, the market rebounded and, by 2017, luxury found its way to the “new normal.”

That new normal has been characterized by a casualization of fashion. Those responsible for the new era—Balenciaga creative director and Vetements designer Demna Gvasalia and others like designer Gosha Rubchinskiy—have used utterly average items like sneakers and parkas to communicate a broader definition of luxury.

data point

21.4%: The amount of traffic to luxury brand websites that comes from a shopping site

Case study: A tale of two Pradas

Is it possible there’s such a thing as being too early to a trend in luxury?

In the late-90s, Prada’s debuted its separate Prada Sport line (aka Linea Rossa). Despite industry praise, Prada discontinued Prada Sport in the mid-2000s due to disappointing sales. But by 2018, fashion—doing what it does—had moved on to new trends, namely the rise of streetwear and a simultaneous longing for 90s-era nostalgia.

At the beginning of 2018, Prada relaunched its Linea Rossa line, though Miuccia Prada dismissed suggestions that the collection was for streetwear-obsessed millennials. Early results suggest a notable commercial success.

It couldn’t have come at a better time for the Milan-based fashion house. Just two years ago, in 2016, Prada recorded its lowest group profit margin in six years and sales were down 10% at the flagship brand. A combination of digital neglect and beautiful clothes that didn’t resonate with a shifting market led to the decline.

“That was a moment when luxury brands were really focused on creating incredible sneakers, and Prada didn’t necessarily have a ‘hype’ product at that moment,” explains Rachel Tashjian, deputy editor at Garage Magazine. “Still, I don’t think it’s fair to say that Prada missed the streetwear trend—they helped lay the groundwork in the 90s with luxury nylon products, after all. But Prada also is not a brand that ‘taps into’ the zeitgeist in a surface way. It responds to deeper, even psychological trends, which is why I think it was so primed for the turnaround.”

Prada’s recovery plan extends beyond Linea Rossa. According to Deloitte, it includes restructuring and refreshing its product range, renovating its retail network, and investing more in e-commerce and digital marketing.

It seems to be working. Prada was responsible for producing the most popular shirt of the summer, worn by everyone from Jeff Goldblum to Pusha T. The availability of Prada Cloudbust sneakers is up 155% in the last year, exhibiting higher demand for the shoe and more growth than any of the six biggest luxury sneaker players, according to Edited data. And according to market researcher Lyst, Prada’s Match Race sneakers are among the hottest products in Asia. Prada ranks sixth by number of followers of luxury brands on Instagram, though engagement on the platform remains lower than its peers.

data point

346.9 million: The number of Instagram luxury brand followers, which grew 23% in the last year, more than any other social media network

The inside scoop on China’s luxury “daigou” shoppers

As China’s middle and upper classes emerge and expand, Chinese shoppers are increasingly making luxury purchases a top priority during trips to Europe, Australia, and other destinations.

The highest net worth individuals, however, can’t be bothered to shop for themselves. Instead, the ultra-wealthy send “daigou shoppers” abroad to make luxury purchases and bring them back to China. It’s a full-service process that ultimately takes advantage of how much cheaper those products are outside of China. It also comforts shoppers worried about the authenticity of luxury products in mainland China (plus, it presents an opportunity for resale in China.) But the service is being challenged by the Chinese government, which is cracking down on daigou shoppers, and encouraging purchases at home.

The government’s action affects the overall luxury sector. The growth of the industry is closely tied to growth in Chinese consumption. Any disruption to the latter impacts sentiment—and stocks.

What a US-China trade war could mean for luxury

Luxury executives and their shareholders are concerned about the ongoing trade war between the US and China. Though the financial impact is minimal for the time being, there’s another problem brewing: The trade war has catalyzed an “unexpected boom” in China’s lucrative luxury counterfeit business. Protectionism, it turns out, is not fashionable.