The problem with looking for solutions that are “win-win”

We take it at face value when business giants like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, or Marc Zuckerberg say they want to “change the world” and make it “a better place“—that they can do good and dominate the marketplace simultaneously.

We take it at face value when business giants like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, or Marc Zuckerberg say they want to “change the world” and make it “a better place“—that they can do good and dominate the marketplace simultaneously.

Their intentions seem noble, their business prowess admirable. What could possibly be bad about a combination like that? It’s a win-win for everyone.

Or maybe not. Writer Anand Giridharadas, a former New York Times columnist and author of the 2018 bestseller Winner Takes All, argues that we need to listen carefully to the language of the marketplace. It is being applied to contemplate and formulate solutions to societal ills, and it’s infecting morality.

Inside the privileged life

As a 2015 Henry Crown fellow at the Aspen Institute, Giridharadas had the opportunity to work with extremely rich and powerful people who, through their affiliation with the think tank, were trying to brainstorm solutions that improve the world. Beneath the surface were disconcerting contradictions, however. The corporations and individuals sponsoring these talks—Pepsi, Monsanto, the Koch brothers, Goldman Sachs, for example—were also arguably involved in projects that undermine equality and justice and exploit the weak.

Giridharadas couldn’t quite square the noble endeavors with the business strategies.

“You started to realize that it wasn’t necessarily clear that this enterprise we were a part of was truly about world betterment,” as he explained to Krista Tippett in a Nov. 15 interview in On Being. “And I basically became very interested in the silences, what we were not allowed to talk about or what we, just by custom, didn’t talk about when we came together to talk about making the world better.”

The wealthy and powerful were consistently asked to do more good, but no one in the group suggested they do less harm. They were encouraged to give more, but never to take less.

Linguistic predicaments

At least as problematic, Giridharadas would argue, is the positivist language that gets used when the wealthy and powerful do discuss their obligations to society. The terms they have popularized obscure harm and promote a certain kind of success. As he told Tippett:

It’s language like the “win-win,” which sounds great, but in some deep way is actually about rich people saying, the only acceptable forms of social change are the forms of social change that also kick something back upstairs — language like “doing well by doing good,” which, again, is like, “The only conditions under which I’m willing to do good is under which I would also do well.”

It’s important to note that Giridharadas is not anti-business. He reported from India as a foreign correspondent to the Times and witnessed firsthand the positive effects of market forces, which he says “actually valued people according to their talents instead of their caste…or gender.”

In the US, he says, our focus on business as the driving force for good is problematic because we are spiritual about industry. We believe in businesses’ abilities to fix all ills like people once believed in gods.

Risk assessment

Meanwhile, the geniuses running these businesses are frequently unaware of the darkness that’s in all of us and how the tools they create end up being used for good and evil.

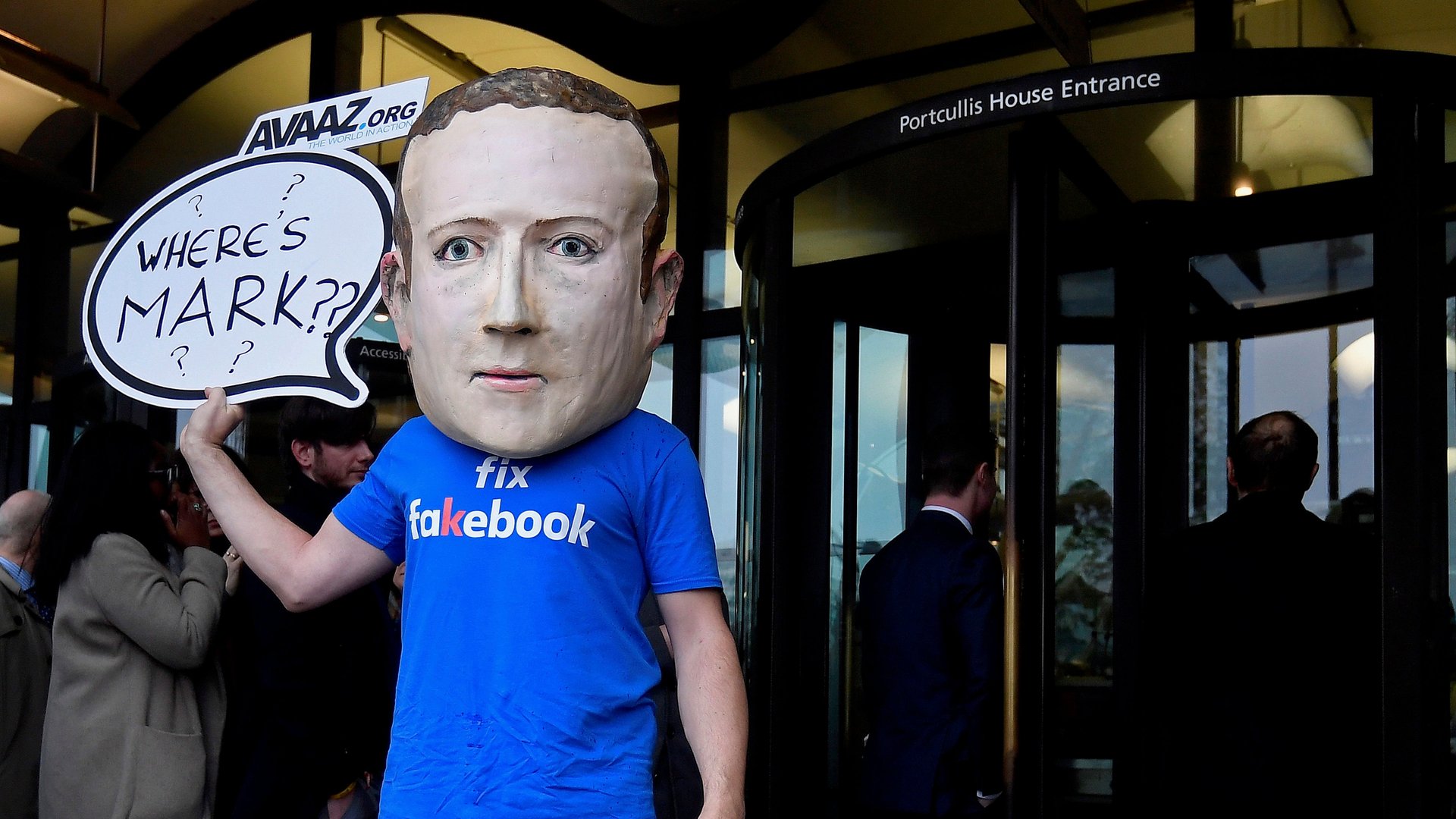

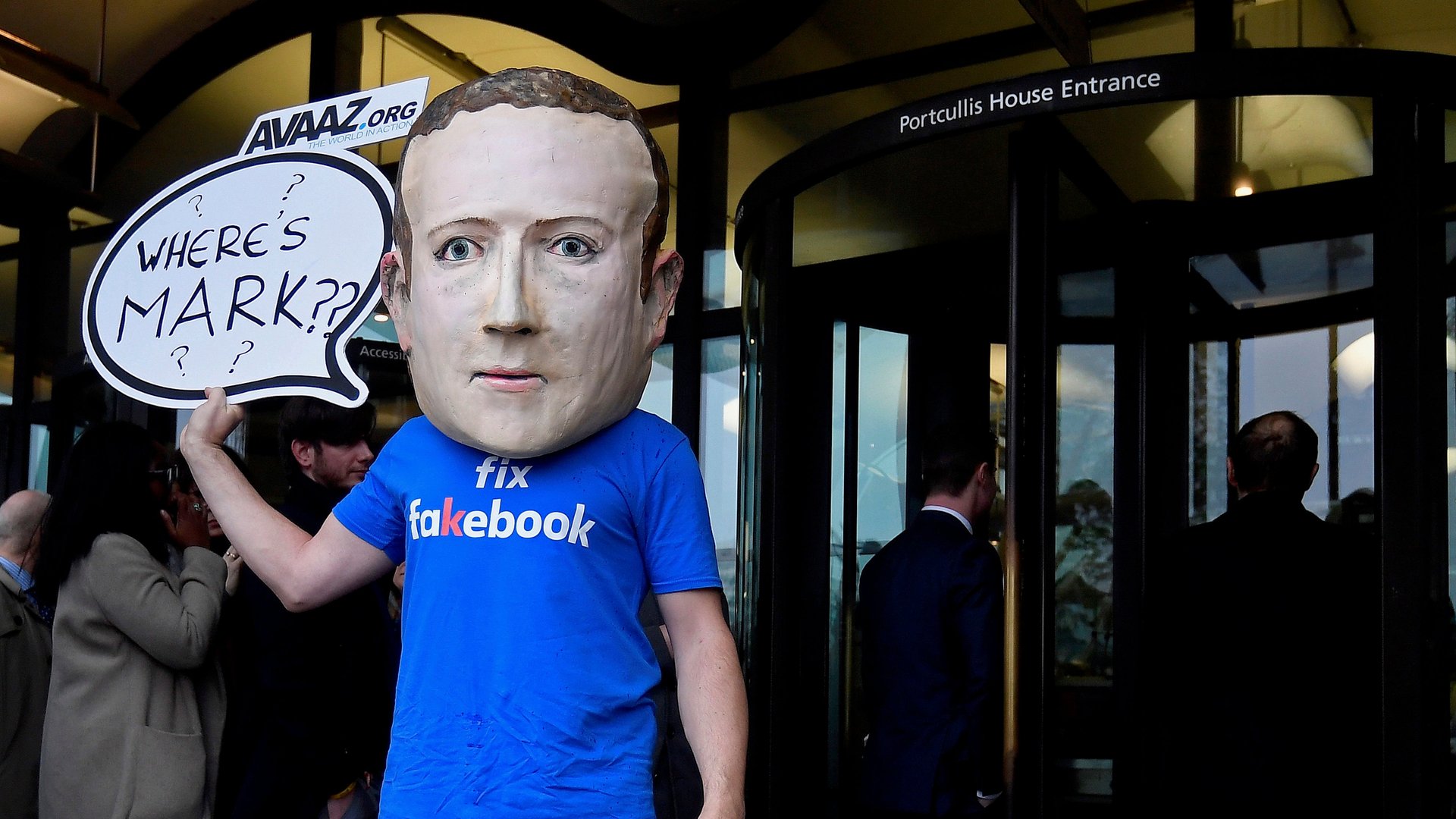

This has been borne out by Facebook’s effort to connect the world, which created the conditions that allowed for the manipulation of elections in the US and UK, stoked violence in Myanmar, and exposed millions of users to data privacy invasions, for example. In 2016, Facebook founder Marc Zuckerberg declared that he would use his wealth to help eradicate all disease “in our children’s lifetime.” Now, we’d be happy if he could just get a handle on his own company.

Indeed, in Silicon Valley, these realizations have sparked a crisis of conscience of sorts. The Esalen Institute in Big Sur, once the home of counterculture intellectual explorations, has become a fashionable place for Google and Facebook workers to cultivate a better understanding of humanity. At Esalen, techies are now studying compassion and connection with the help of specialists. And companies bring in philosophers posing as futurists, like Richard Watson, to instruct employees on what it means to be human, how to think about consequences.

Giridharadas doesn’t believe the tech types and industrialists are solely responsible for solving societal woes. We all construct the culture together—our belief in business giants is part of the problem. As such, he urges us all to consider the language we use and hear and the meanings it obscures so that we too can start doing good.

But he also offers no solutions because being overly prescriptive, Giridharadas argues, is the precise problem of the privileged that he hopes to illuminate with his writing. His job is to call our attention to the problems language sometimes hides. As he told On Being, “I hope no one ever just calls something a win-win again without having a sense of irony around it…that would, for me, feel like an achievement, because I actually think a lot of how you get decent people upholding an indecent system is culture, is vocabulary, is values. If you can start to warp those or twist them around, I actually think you can get somewhere.”