Any plan to improve the global food system must include new technologies

One of the world’s leading scientific journals this week issued an urgent call to global governments to convene what is essentially a Paris Climate Agreement for food.

One of the world’s leading scientific journals this week issued an urgent call to global governments to convene what is essentially a Paris Climate Agreement for food.

Published in the Lancet, the new report is the work of 16 respected scientists who pulled from an immense body of research to propose what they believe is an actionable answer to the issue of feeding more than 10 billion people by 2050 in a way that is environmentally sustainable. At its core, it calls for eating more vegetables and less red meat and dairy, and for shifting investment used to grow corn and soybeans for animal feed to more nutritious crops that can be eaten directly by people.

The proposal is critically flawed.

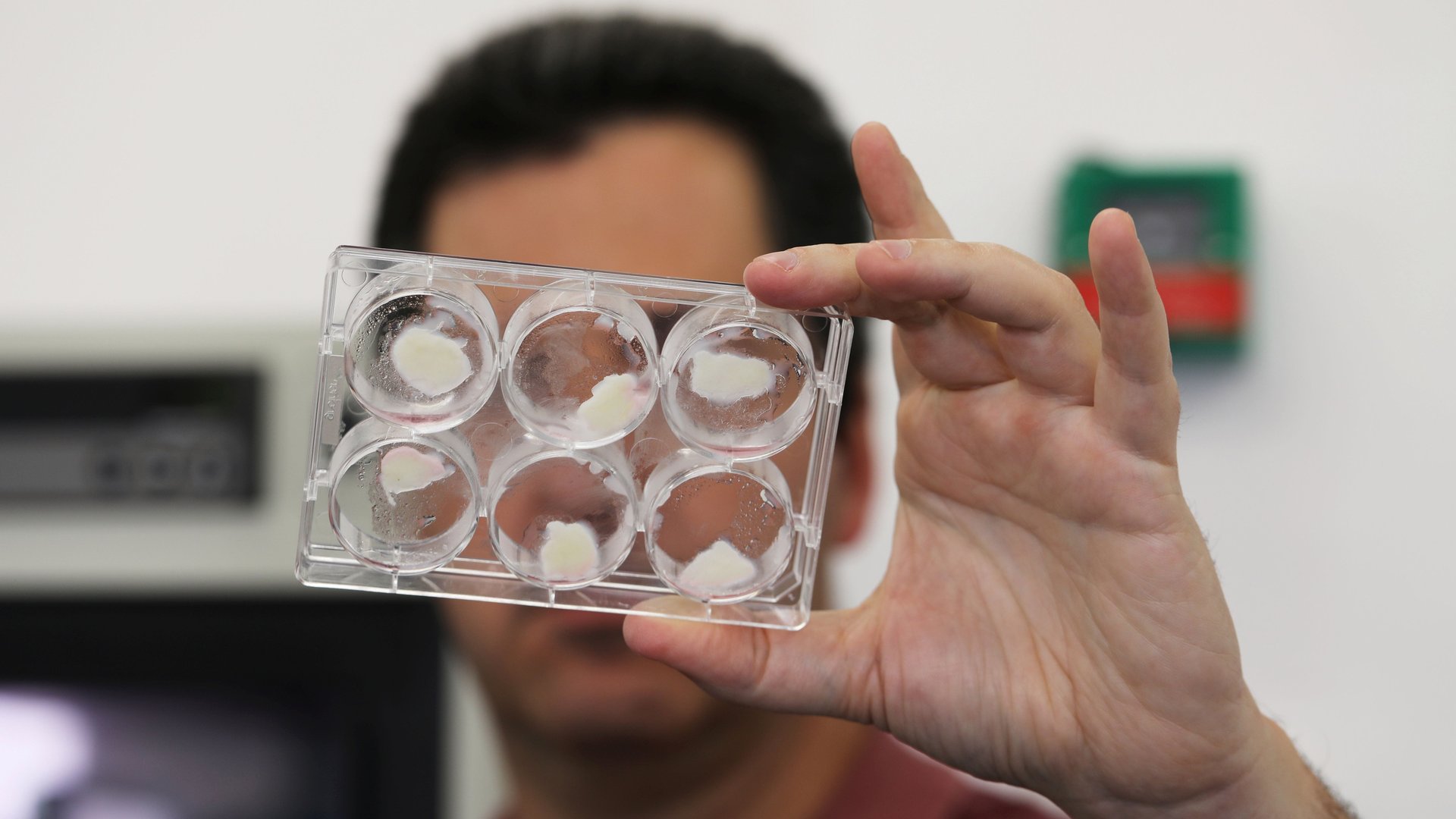

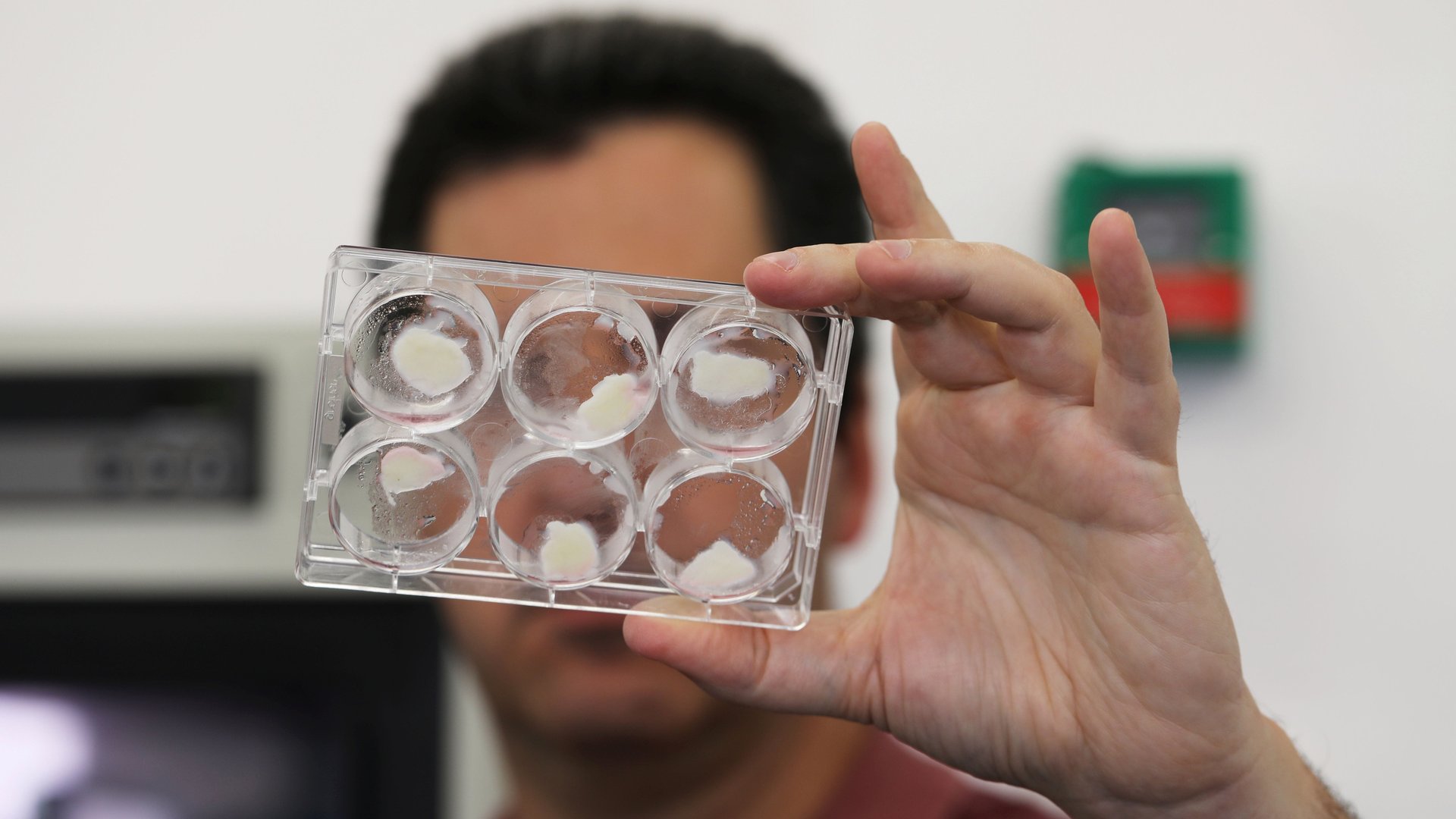

Conspicuously, it does not address or acknowledge the countless food-technology efforts underway to solve the very environmental sustainability problems its authors bemoan. They never mention the concepts of cell-cultured meat and fish, the advances of plant-based meat, the successful molecular-rejiggering of healthier sugar molecules, or the technology that genetically engineers yeast to sustainably produce the same proteins that appear in dairy. Nor does the report mention that the single biggest barrier to getting many of these new, arguably more sustainable foods to market are government regulators and not the lack of scientific know-how.

In some ways, the proposal laid out by the report’s authors is a repeat of what people have heard for a long time: Eat more vegetables, eat less meat, consume in moderation. The only difference is the urgency in which that directive is being delivered, and the vociferous call on governments to take more action.

The report warns that even the slightest increase in red meat consumption would derail their proposed plan, dubbed the “Great Food Transformation.” But it doesn’t acknowledge the force of ingenuity. While humanity is on the path to demand and eat more meat than ever, a well-documented trend, entrepreneurs and others are working hard to carve out a viable way to address that.

Can you decry the red meat and dairy industries as primary polluters (and link them to poor health in some countries) but not seriously talk about technology-driven alternatives? The word “bioengineered” doesn’t appear in the report at all. And “technology” pops up only once in relation to how it might assist in sustainably meeting food-production goals. Meanwhile, companies in Israel, Holland, America, Japan, and Singapore are positioning themselves to begin bringing scaled-up versions of cell-cultured meats and seafood to dinner plates.

The report’s omissions are indicative of a misplaced fear of technology, problematic preconceived notions about the naturalness of food we already eat, and a persistent, seemingly futile push for people to embrace eating more nuts and beans to get their protein. One of the lead authors of the Lancet report, Walter Willett, chairs Harvard University’s nutrition department. In a November 2018 interview with WBUR in Boston, he said new technologies won’t be the solution for food sustainability issues, and instead recommended people turn to soy, nuts, and fish to avoid red meat and dairy.

This type of response goes against the grain of consumption trends, and demonstrates a lack of understanding about just what new food technologies have to offer. In some ways, it echoes the aversion some people have had toward genetically modified foods, even though there’s virtually no scientific evidence showing that they are bad for human health. Such attitudes create suspicion toward Crispr-tinkered cocoa beans, more durable tomatoes, and other foods that science has made more efficient.

The collision of technology and science hasn’t necessarily made better-tasting or more nutritious foods, but it has created more efficient foods. For that reason, the omission of technology’s role in helping to create a more just and sustainable food system is an incredible oversight on the part of the report’s authors. It’s a decision linked, more broadly, to a fantasy that the produce and meat we buy at the grocery store today—no matter how intensely it’s been bred to perfection by humans—is somehow more closely linked to the natural world than those that are the product of some technological tinkering.

If we’re going to offer an answer to climate change that’s bold enough to be dubbed “the Great Food Transformation,” the plan will have to be built, in part, on new technology, which is a sturdier foundation than beans, nuts, and the far-flung hopes that governments will swiftly regulate industries into doing the right thing.