Political crises, market volatility, and profit warnings set a bleak backdrop for Davos

“It’s a time of enormous ebullience.” “We are in an exceptionally favorable context.” “The world is in a good place economically, about as good as it could be.”

“It’s a time of enormous ebullience.” “We are in an exceptionally favorable context.” “The world is in a good place economically, about as good as it could be.”

That’s what CEOs of the world’s largest financial firms said last year at the World Economic Forum’s annual gathering in Davos, Switzerland. As this year’s meeting officially kicks off, with “Globalization 4.0” as the theme, the tone among global business and political leaders is much less jubilant.

Most immediately, 2018 ended with a severe bout of market volatility that sent stocks around the world plummeting. In fact, stocks never rose that much higher than they did during the week of the Davos summit in 2018. At the end of the year, meanwhile, almost every major asset class ended in the red.

Even as markets have staged a recovery so far this year, there are plenty of things to worry about. Trade tensions and protectionism, particularly between the US and China, have curtailed global economic momentum. Companies are also warning that profits have peaked, with Apple starting the year with a profit warning. There are looming concerns about the rise in corporate debt, especially in leveraged loans and the shadow banking system. And then there’s the existential threat of climate change.

The World Bank predicts that economic growth in advanced economies will slow this year to 2%, from 2.2% in 2018, and growth will stall at 4.2% in emerging markets. The partial inversion of the US yield curve has traders worried, since that measure has some history as a recession warning sign. Meanwhile, the IMF warns that governments are not sufficiently prepared to combat the next economic downturn, which is coming closer as we enter a “late-cycle” expansion. “There is no guarantee that [current financial defenses] will be sufficient to keep a ‘garden variety’ recession from becoming another full-blown systemic crisis,” David Lipton, deputy managing director of the IMF, wrote last week.

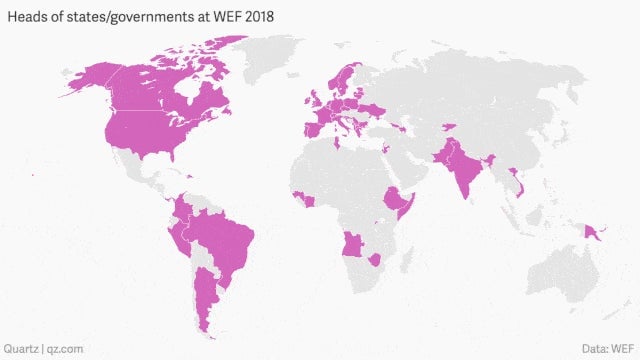

A slew of national political crises have led to some notable omissions of world leaders in Davos this year. Donald Trump and the rest of the US delegation cancelled their trip at the last minute as the government shutdown shows few signs of resolution any time soon. British prime minister Theresa May won’t be making a third appearance in three years at the Congress Hall as she stays home to present a revamped Brexit plan to parliament, after her original was voted down in by a huge margin. France’s Emmanuel Macron, one of last year’s Davos darlings, is at home after the gilet jaunes (“yellow vests”) protests enter their 10th destructive week. Others big names from last year who are skipping Davos in 2019 include Canada’s Justin Trudeau, India’s Narendra Modi, and Argentina’s Mauricio Macri.

Brazil’s newly elected populist president Jair Bolsonaro is the first head of state to appear on the main stage at WEF this year. Other noteworthy leaders giving speeches this week include Germany’s Angela Merkel and Japan’s Shinzo Abe.

If the Davos set offer up a somewhat pessimistic outlook on the world, that might not be such a bad thing. Betting against the Davos consensus has normally proved a winning strategy. Just look at last year, as the leaders rallied around record-high stock markets and marveled at the synchronized upswing in global growth: Just over a week after they returned home, volatility hit the markets hard. So while last year’s ebullience may have marked the peak of the economic cycle, it could also be that the pervasive gloom this year is overdone and perhaps things aren’t as bad as they seem.