A parliamentary report lays bare how badly the UK fails its youngest kids

The UK parliament says the government has failed to develop a coherent policy to support children from birth to age four as a way to tackle the significant achievement gaps between the country’s rich and poor kids. In a report published today (Feb. 7), it calls on the government to fulfill its multiple unmet promises to invest more in the early years of life.

The UK parliament says the government has failed to develop a coherent policy to support children from birth to age four as a way to tackle the significant achievement gaps between the country’s rich and poor kids. In a report published today (Feb. 7), it calls on the government to fulfill its multiple unmet promises to invest more in the early years of life.

“There seems to be little strategic direction to government policy on early years,” the report states, noting many promises made, but not kept. Those include a “life chances” strategy, introduced by former prime minister David Cameron, but never published, and little focus on the early years in the government’s social mobility action plan. It also criticized part of the government’s flagship childcare policy, which offers 30 hours of free care to many UK families, for not targeting those who need it most. The subsidy includes a large share of well-off parents, leading one witness to call it a “car crash.”

The report also highlights the gap between children of different income levels. According to the Sutton Trust, a UK charity, the gap in how rich and poor kids perform on tests is about 4.3 months when children start school at age five. That gap more than doubles (pdf) to 9.5 months by the end of primary school, and doubles again to 19.3 months by the end of secondary school. And yet it’s rich kids who tend to go to preschool more than poorer ones, entrenching the disadvantage.

The report calls for a two-pronged approach: investing in quality preschool, including the early years workforce, and supporting a “strong home learning environment” for low-income families, with a focus on improving communication and language development.

As an example, it cites a program in Manchester, where kids are assessed eight times between 0–5 years old to identify who might need additional help, including for speech and language development. “This model should be followed across the country,” it advises.

The committee collected evidence from 60 witnesses, concluding, among other things, that:

- Quality early years provision has a lasting positive impact on child outcomes;

- High quality early years provision narrows the gap between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged children;

- The qualification level of staff in the setting improves quality.

Little of this evidence is new. Research shows that children aren’t born with predestined gifts or fixed intelligence. In the first few years of life, their brain development is intense (pdf)—and built in large part on the love and support offered by parents and caregivers. Infants and young children need parents who talk to them, sing to them, and show them affection. These actions form the neurological pathways that determine how children think and feel.

But governments have generally failed to develop an integrated approach to investing in the earliest years that makes sense. It’s not about education—one-year-olds are not in school. And it should include support for families and caregivers, through home visiting programs and high quality child care. Some countries, like Chile, have a comprehensive approach. But most governments do not.

This is too bad considering the evidence. If countries improve the environment for the neediest kids and support their caregivers, they can help ameliorate the negative impacts poverty has on children’s brains and their development.

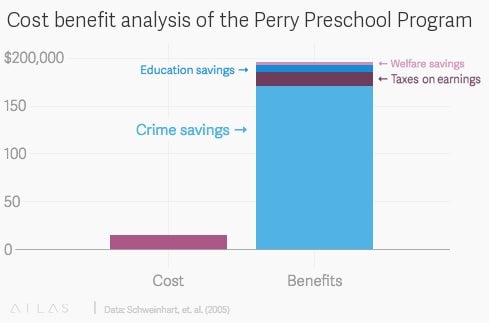

Consider the Highscope/Perry Project, which studied 123 children living in poverty in the small city of Ypsilanti, Michigan. From 1962 until 1967, kids aged three and four were randomly divided by researchers into two groups. One group attended a high-quality preschool program, and a comparison group received no preschool program. The effect on the kids, who were were tracked until they were 40, was dramatic. Those who attended the preschool made more money and committed fewer crimes later in life. They were more likely to hold a job and to have graduated from high school than the group that didn’t have a preschool education.

The case for prioritizing early childhood policies was elevated by Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman. As founder of the Center for the Economics of Human Development at the University of Chicago, he demonstrated the economic case for why the best investment a policymaker can make is in the earliest years of childhood.

“The highest rate of return in early childhood development comes from investing as early as possible, from birth through age five, in disadvantaged families,” Heckman said. His work showed that every dollar invested in a child over those years delivers a 13% return on investment every year. “Starting at age three or four is too little too late, as it fails to recognize that skills beget skills in a complementary and dynamic way,” he said.

Advocacy groups welcomed the report. The early years “are a vital time in the life of any child and play a significant role in shaping who they will become and the opportunities they will have,” said Kevan Collins, head of the Education Endowment Foundation, a non-profit group that wants to close the gap between family income and educational attainment. “While the link between family income and learning even among young children is clear-cut and hard to break, it is not inevitable.”

The report called for providing infants and toddlers from disadvantaged homes access to high-quality, evidence-based nursery schools, with well-trained and skilled staff. Specifically, it says the quality of teaching in preschools is just as important to outcomes as it is in other stages of education.

The report also called for more UK-based evidence on home visits by trained professionals. Programs around the world have already shown how effective such visits can be (notably Jamaica and Brazil, and the Family Nurse Partnership in the US).

Its findings reinforce how much parents, with support, can help their young children thrive. “It is unarguable now, after decades of evidence that parental engagement makes a difference,” Collins said.

The attainment gap 16-year-olds face in the UK has serious consequences. The Education Policy Institute, a think tank, estimates that “at the current rate of progress, it would take a full 50 years to reach an equitable education system where disadvantaged pupils did not fall behind their peers during formal education to age 16.”

Starting early could help.