A language from Asia is rapidly closing in on the West, threatening the longstanding supremacy of the Latin alphabet. This means that one day soon, it won’t be merely alphabet letters that Western mobile users tap onto their screens. It may also be whistling kittens, or a bear dancing the hula.

This is a visual vocabulary far more complex than emoticons, the icons constructed from punctuation marks, such as :-), or emoji, the preset pictographs that occupy a single character of text on a smartphone or computer (here are some examples).

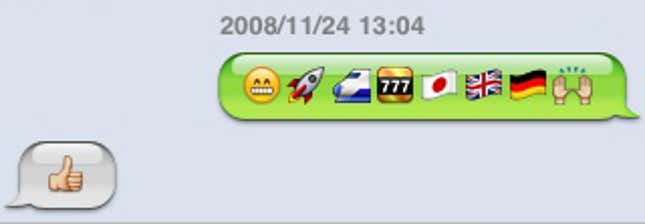

Both of those you can type using the standard keyboard. This, you can’t:

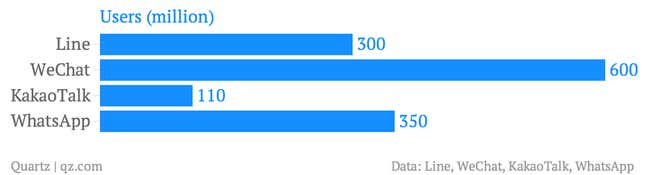

“Stickers,” as these social messaging apps are called, are wildly popular in Japan, Korea and China and made by major companies in each: Line in Japan, KakaoTalk in Korea and WeChat in China. But as these three apps scrabble for market share outside of North Asia, the question is: Will that region’s love of stickers translate elsewhere?

That’s of particular importance to Line, which is rumored to be mulling an IPO in the US. The Korean-owned, Japan-based app is betting a big part of its business that mobile phone users who are, say, fans of Barcelona’s soccer team will one day want a bobble-headed Lionel Messi dashing across their screen.

What’s a social messaging app?

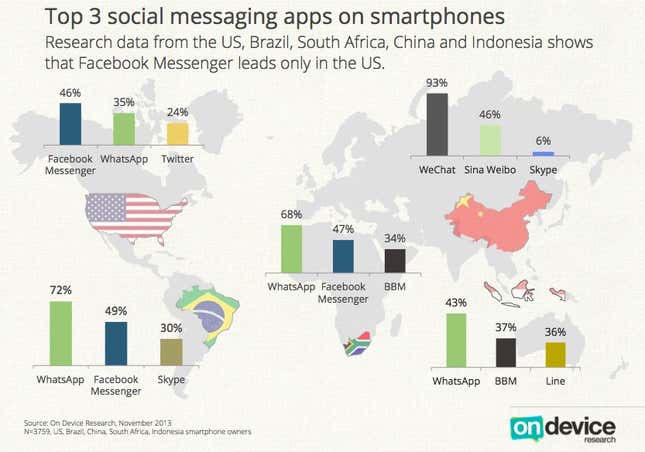

For Westerners, a more familiar company than Line, WeChat or KakaoTalk is WhatsApp, an American company with a global presence. Some 90% of smartphone users in Mexico, Italy and India have downloaded WhatsApp (for a total of 350 million active users), which allows its users to send text messages to each other via a Wi-Fi connection, instead of racking up charges on their phone bill.

Line, KakaoTalk and WeChat have more bells and whistles than WhatsApp, which limits users to sending text and emoji (it doesn’t offer its own stickers). These souped-up apps draw on elements from Facebook, Instagram and gChat and let users send and exchange a much wider range of content to a much broader audience. Features include chatting via instant video, recording short voice messages stored as memos (it’s faster than typing, and more personal) and sending stickers.

How do sticker companies make money?

Just as their content offerings do, the business models of WeChat, KakaoTalk and Line differ from WhatsApp, too. The Asian sticker apps can all be downloaded for free; WhatsApp simply charges users $1 to download it, limiting use to a single device.

WeChat, KakaoTalk and Line make their money by hooking their users on free games they can download in the app, charging them for virtual items. The clear leader is KakaoTalk, whose users bought $311 million in in-app game items (virtual items like swords or magic potions, or new lives within the game) in the first half of 2013. WeChat’s plan for monetization remains less clear, but since its parent company, Tencent, is a mobile games powerhouse, it will probably rely heavily on games to drive revenue.

Aside from selling in-game items, the other way social media apps bring in money is by selling sticker packages, which you can buy in stores featured within each app:

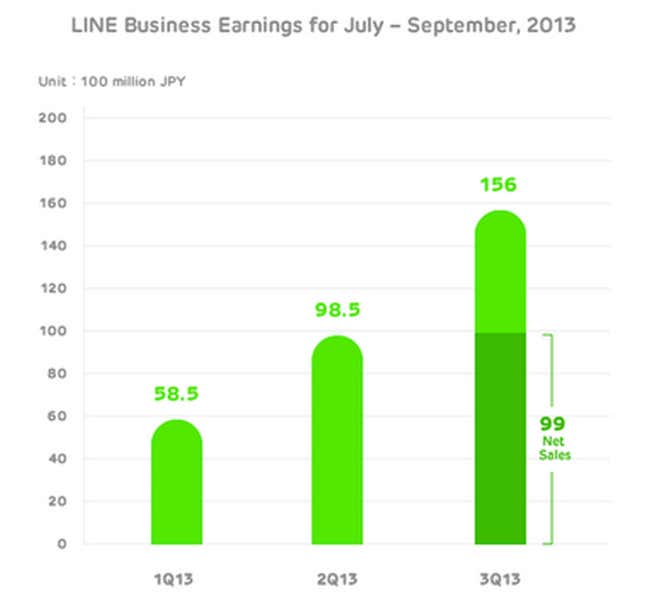

Line’s $10 million-a-month sticker business

Whereas KakaoTalk and WeChat get a small portion of their revenue from stickers, Line earns around 20% of its net sales from selling stickers and 60% from games (the rest comes from corporate services). Line didn’t break down its Q3 data, but in Q2, its sticker business brought in $27.4 million, or 27% of its revenue. By August, Line sold its 1 billionth sticker, marking one sale for every seven messages sent. Line says it’s now making more than $10 million a month selling stickers. Here’s the overall trend of its revenue growth:

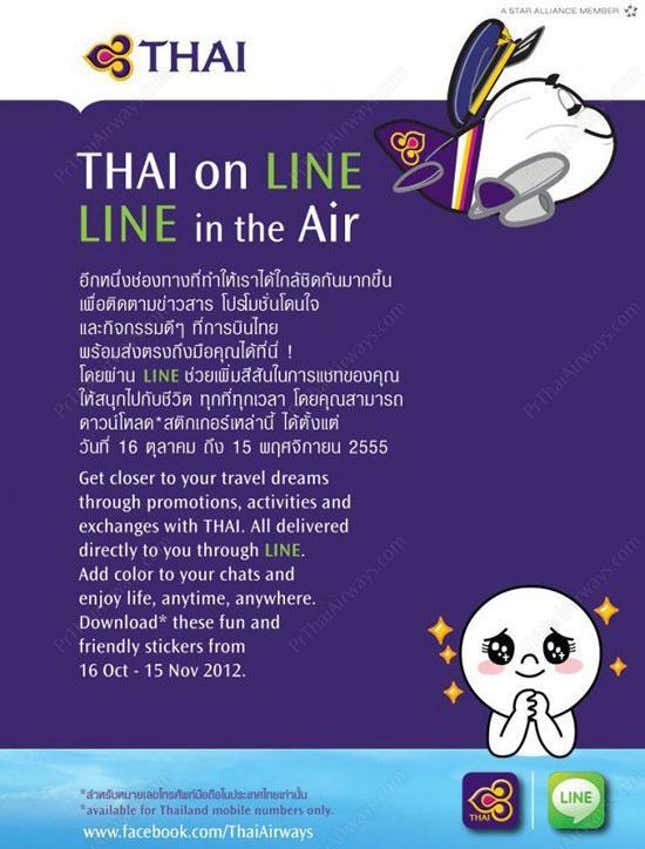

Another way Line is making hay off stickers: In Q2, it brought in more than $20 million in so-called “sponsored” stickers, which businesses use to promote their products. Users can download them from the sticker store just as they would ordinary stickers. Here’s an example from Thailand, a country where Line has 20 million users and is trouncing the competition:

Line and the other apps offer a way for celebrities to interact with their fans in the same way many now do through Twitter (which, as it happens, identified Line and Kakao as possible competitors in its IPO filing). Since launching an account in early October, Paul McCartney now has nearly 7.9 million Line followers, likely the result of a promotion that gave users free Paul stickers like this one when they followed his account:

Before there were stickers, there were emoticons and emoji

The roots of the sticker business trace back to Japan, by way of Pittsburgh. That’s where, in 1982, a Carnegie Mellon University professor invented what we now call emoticons to signal to other chatroom participants that he was joking. Though they can get quite elaborate, emoticons are limited to what you can create—and what people are likely to interpret—from a combination of common keyboard symbols.

Next came emoji. Instead of a string of punctuation that looked sort of like a face, emoji are pre-determined pictograms that appear when a user types in specific codes into a given interface. For example, on a platform that recognizes emoji, typing in your standard “:-)” will generate an upright yellow smiley face. Here’s an example of some emoji, from Flickr user mroach:

Emoji first appeared in the mid-1990s at Docomo, a Japanese telecom company, where Shigetaka Kurita built them for pagers. There’s a reason they came from Japan, according to a masterful history of emoji by The Verge:

In Japanese, personal letters are long and verbose, full of seasonal greetings and honorific expressions that convey the sender’s goodwill to the recipient. The shorter, more casual nature of email lead to a breakdown in communication. “If someone says Wakarimashita you don’t know whether it’s a kind of warm, soft ‘I understand’ or a ‘yeah, I get it’ kind of cool, negative feeling,” says Kurita. “You don’t know what’s in the writer’s head.”

Another reason for their invention is more clearly universal:

Face to face conversation, and even the telephone, let you gauge the other person’s mood from vocal cues, and more familiar, longer letters gave people important contextual information. Their absence from these new mediums meant that the promise of digital communication—being able to stay in closer touch with people—was being offset by this accompanying increase in miscommunication.

“So that’s when we thought, if we had something like emoji, we can probably do faces. We already had the experience with the heart symbol, so we thought it was possible.”

Emoji are now popular enough that even WhatsApp features them. And they’re plentiful enough that they can narrate a Katy Perry song:

As for stickers, Line and Kakao Talk offered them early on, but it was Line that made them famous. Demand for stickers has birthed a $500 million a year industry (link in Chinese), according to Global Enterprise Magazine, fueled mostly by illustrators and animators in China.

Why East Asians like saying it with stickers

Regardless of what language you’re using, emoticons, emoji and stickers are all useful in adding emotional nuance to text-based interactions.

But there’s also a more mechanical reason for the popularity of emojis and stickers in Asia. Even with predictive text, typing out Asian scripts on smartphones designed for the Latin alphabet can be more tedious than just punching in letters. It can sometimes take a while to find the right Chinese characters on a phone, or to switch among the different scripts of Japanese. (Characters are particularly cumbersome given how many homonyms there are.)

Anecdotally, this is a big reason why recorded voice memos are so appealing to Chinese and Japanese users. It’s also much faster to use a sticker to convey complex emotions (e.g. frustration) or even specific situations, like coming down with a cold.

This brings us back to Line’s potential to expand its booming sticker business beyond Asia. If you’re living in a place where the written language allows you to type “gotta cold” faster than it takes to locate your sneezing bear sticker, it’s hard to see the value of Line’s offerings. That’s not to say Western users won’t use stickers—just that if they do, saving time won’t likely be why they value them.

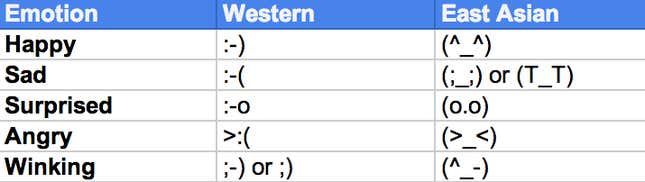

:-) or (^_^) ?

So far, social messaging apps have focused on Asian tastes and expressions, which could hurt their businesses abroad. People from different cultures read emotions from facial cues distinctively. That’s why “happy” looks like “:-)” in the West and (^_^) in Asia. Here’s a breakdown of some examples:

The style of most stickers fits into Japan’s “kawaii,” or “cute,” culture (think Hello Kitty), which can come across to people outside North Asia (and many within, for that matter) as sappy, childish or creepy.

Would stickers reflecting local styles and themes be more appealing? Akira Morikawa, Line’s CEO, thinks so. “A bow [meaning a person bowing in a sticker] may work in Japan,” Morikawa told the Japan Daily Press, “but not in other countries.”

The case of Spain suggests that culture-specific stickers might take. After a big mass-media push there, Line now claims 15 million users in Spain, putting it right behind WhatsApp. Some of Line’s promotions there resemble its universal marketing approach, such as its use of the two lead stickers characters, Cony the rabbit and Brown the bear, who are now national icons in Japan:

But the company is also catering to local tastes, such as hiring soap celebs Hugo Silva and Michelle Jenner to banter with stickers in this ad:

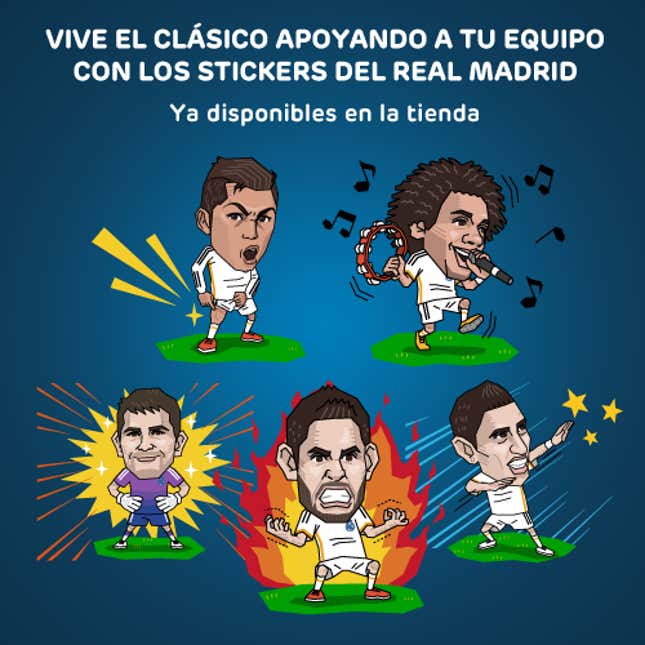

Line also latched onto Spanish soccer fervor, designing stickers featuring professional players from Barcelona and Real Madrid:

Jeanie Han, US CEO of Line, says the sticker strategy has paid off. “In Spain it just kind of grew organically,” Han told TechCrunch. “I think it had something to do with the fact that the Spanish people are very passionate, and they’re very expressive.”

Case in point: “As Spaniards like to express our feelings using our bodies and facial expressions the stickers are very cool,” a 29-year old Spanish animator living in Tokyo told Reuters. “I can never stay angry at my boyfriend long if he sends me a cute sticker.”

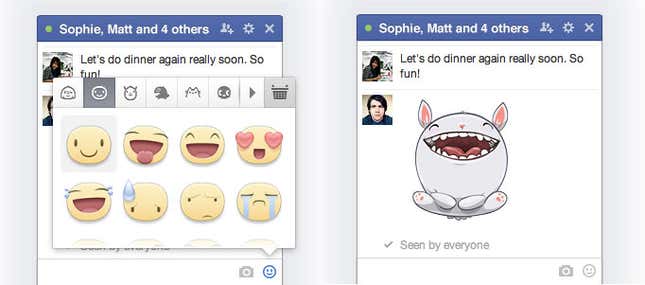

Line’s thinking is attracting some high-profile imitators. Viber, a similar social messaging app to WhatsApp, just rolled out an in-app store with 1,000 stickers, Apple iOS recently started including stickers, and Facebook Messenger launched stickers for the first time in July, including some distinctly Japanese-style ones:

But most of those services are free. That puts more pressure on Line to justify its fees for more elaborate stickers.

In Line’s global conquest, the US is the final front

Earlier this month, Line announced its 300 millionth registered user; 80% of those are outside its home base of Japan, says the company. That means it must be doing something right.

The US market is the crown jewel—or a “high priority,” as Line’s Han calls it. “People spend more here in the States than any other top territory relative to the user base,” Han told the New York Times last March.

But even as American companies like Facebook roll out stickers, Line is leaving its American invasion for last. After an initial push in early 2013, Line pulled back from the US market, designing fewer stickers for American users and buying less advertising. Instead it focused on more promising markets like Latin America. Competition and its multiple ethnicities and cultures mean the American market “needs more care,” as Han recently told The Next Web’s Jon Russell.

High marketing costs in the US may be a deterrent. ”You can do TV marketing in Indonesia, you can do TV advertising in Spain,” Serkan Toto, a Tokyo-based tech consultant, told Reuters. “But if you want to do the same in the United States then your coffers must be really full.”

More cash for US marketing would need to come from Naver, Line’s $20-billion parent company or other “various possibilities for future expansion” such as its rumored US IPO. But then, a successful US IPO might require more upfront marketing to attract investors and boost its valuation. In sticker terms, the dilemma of which route to choose might look something like this: .