SpaceX takes its biggest step toward flying people into space

A long-awaited dress rehearsal for the US return to human spaceflight is slated for the wee hours of Saturday morning, with everything in place but the astronauts.

A long-awaited dress rehearsal for the US return to human spaceflight is slated for the wee hours of Saturday morning, with everything in place but the astronauts.

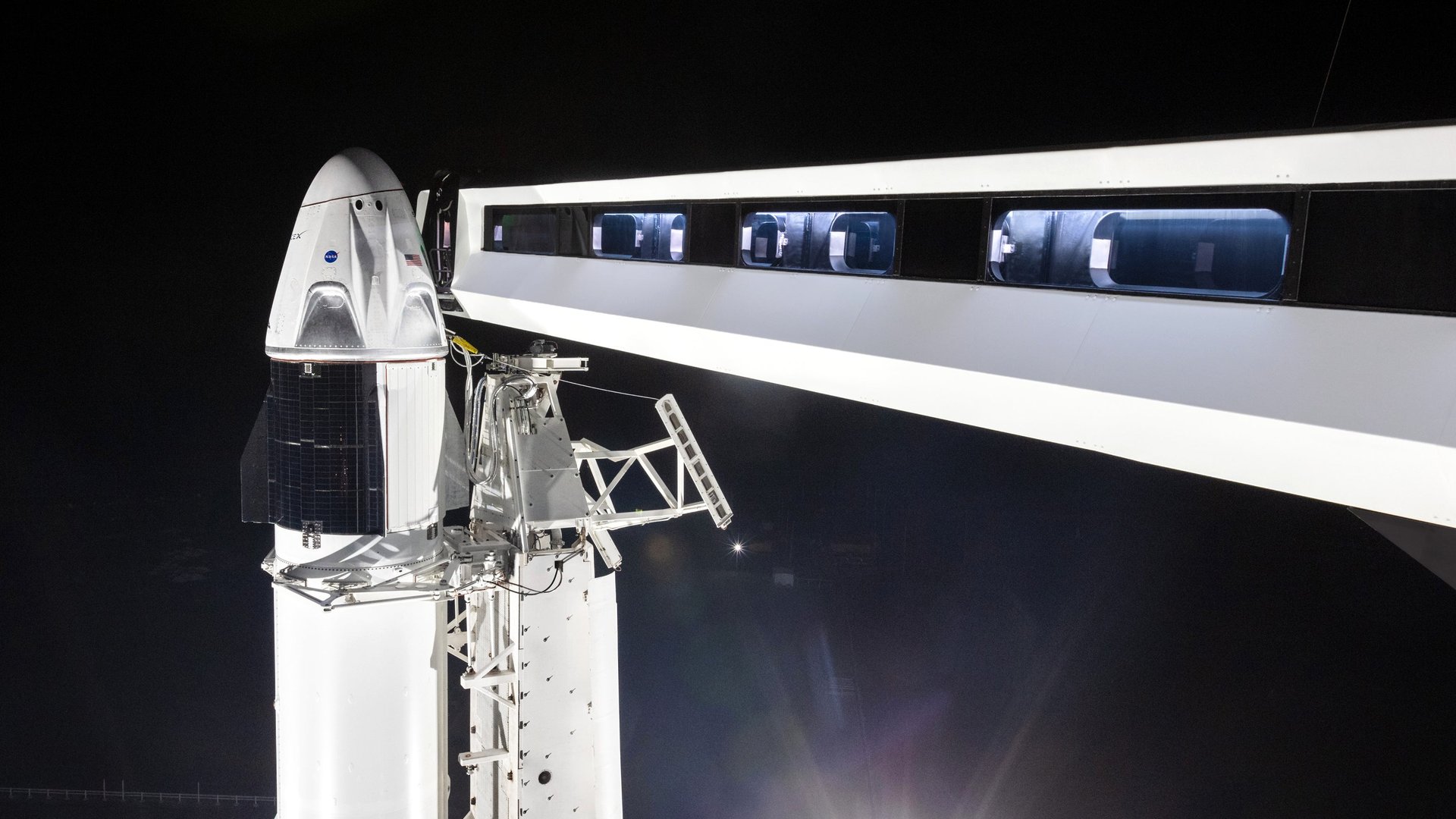

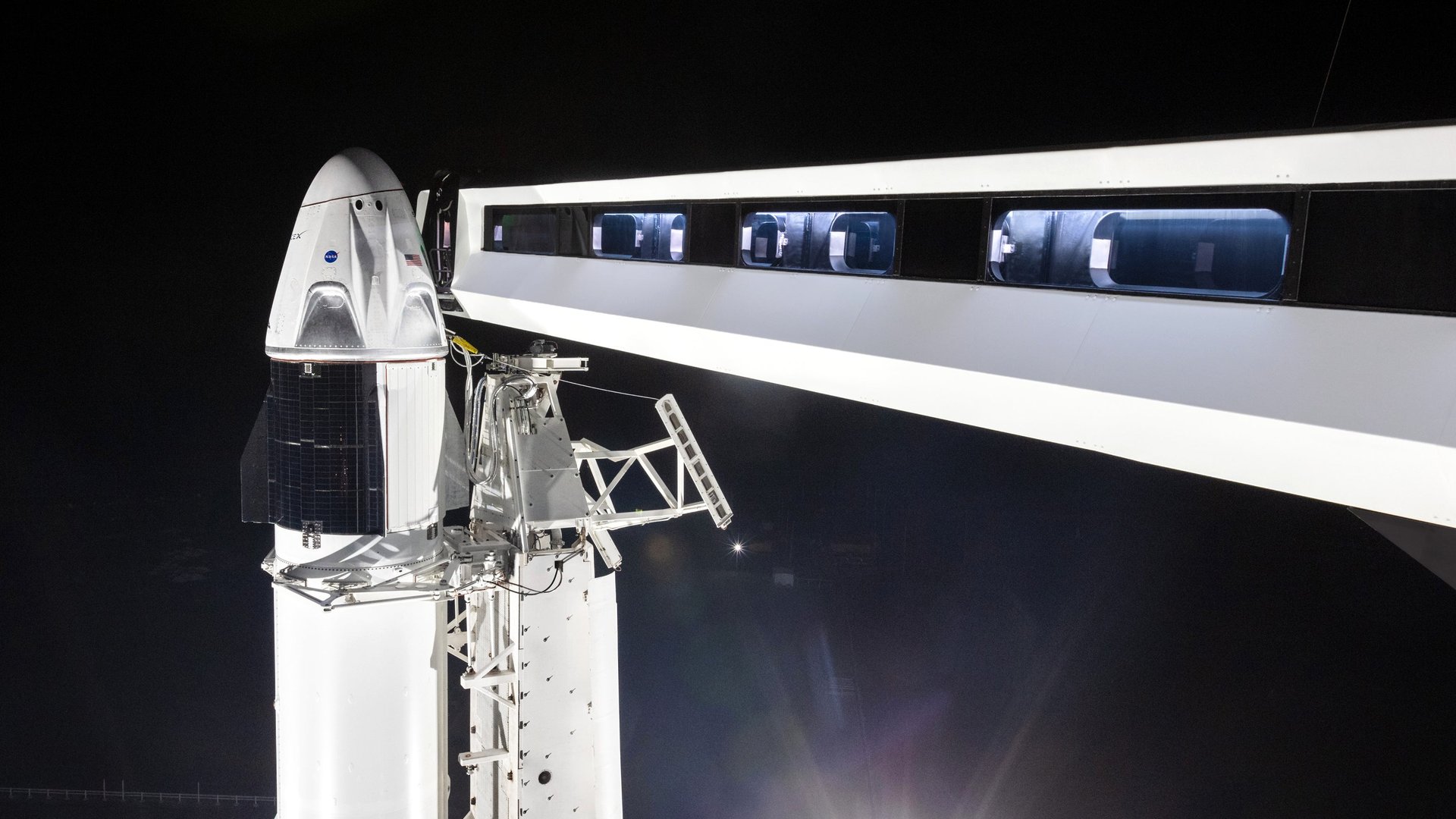

SpaceX will launch the first uncrewed demonstration mission of a Dragon space capsule fitted to carry humans (but not actually carrying humans in this demo) at 2:49am eastern time on March 2, from the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. After being carried into space on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, it will attempt to dock with the International Space Station (ISS) a day later, and on March 8 return to Earth via parachute landing in the Atlantic Ocean.

If all are successful, it will mark a major milestone for the US space program’s pursuit of public-private partnerships and Elon Musk’s dreams of a Martian retirement.

“We need to execute a successful mission with SpaceX,” Kathy Lueders, the NASA executive leading the space agency’s commercial-crew partnerships, said at a pre-launch briefing last week. “We need to take all the learning out of this mission and apply it to our upcoming crew missions.”

If everything goes as planned, SpaceX could fly astronauts as soon as July. NASA astronauts haven’t flown to space from the US since the end of the space shuttle program in 2011, though Virgin Galactic, a private company, flew (non-NASA) humans on brief trips to space earlier this month and in December 2018.

“SpaceX learned a lot over the past 70 [Falcon 9] missions, the past 16 Dragon missions [to re-supply the ISS],” said Hans Koenigsmann, the company’s chief launch engineer, said on Feb. 28. “Everything we’ve learned [has been applied] in this particular Dragon version in this particular mission.”

Night owls in the US and space watchers all across the globe can track the action on SpaceX’s livestream:

The Crew Dragon capsule, as it’s called, is 16 ft tall and 13 ft in diameter, with room for seven astronauts packed tightly together. On this mission, it will carry a mannequin named Ripley—in honor of Ellen Ripley, the hero of the Alien films played by Sigourney Weaver—which will be covered with sensors to measure how the flight will affect future passengers.

“We instrumented the crap out of this vehicle,” Lueders said on Feb. 28. Besides the sensors attached to Ripley, the craft is covered with pressure, sound, vibration, temperature, and radiation monitors. NASA will also take advantage of the flight to bring up some 400 lb of hardware and supplies for the ISS crew, and return a broken space-suit component back down to Earth for further investigation.

Docking the spacecraft with the ISS is the riskiest maneuver on the agenda. SpaceX’s cargo spacecraft are usually grappled into the station by astronauts operating a robotic arm, but this spacecraft will become the first to automatically park at ISS’ new International Docking Adapter, installed in 2016.

While safety precautions should keep people away from danger in the event of a launch failure, the three-person crew currently aboard the ISS could be at risk if something goes wrong during during docking maneuvers. Last week there were still concerns at Russia’s space agency, a co-owner of the ISS, about the flight computers on the SpaceX Crew Dragon. Many spacecraft have two entirely separate computer systems to ensure redundancy, but SpaceX relies on software measures to keep its single computer working.

To ensure a careful approach, ISS managers had carefully planned the new spacecraft’s docking procedures to include a number of pauses and retreats, but to gain Russian approval, they also agreed on new protocols for the crew to seal off sections of the station and be prepared to abandon it in a Soyuz escape craft in the worst-case scenario.

Seventeen years of effort

Founded by Musk in 2002, SpaceX established a key partnership with NASA in 2006 to fly cargo to the ISS. That allowed the company to build its Falcon 9 rocket, which currently dominates the commercial space-launch market. But Musk’s aspirations have always been interplanetary, and that means developing the vehicles necessary to safely carry humans into space.

“Human spaceflight is basically the core mission of SpaceX, so we are really excited to do this,” Koenigsmann said last week.

This launch is part of NASA’s novel spaceflight program in which private companies design and operate spacecraft under agency supervision, but it is untried when it comes to flying humans. The commercial crew partnerships have allowed NASA to put the bulk of its spacecraft development funding toward the deep-space Orion capsule—some $16 billion so far and still growing before its first launch—while splitting about half that amount, about $8 billion, between SpaceX and Boeing for two separate low-Earth orbit spacecraft that should debut this year. Boeing is expected to do its own uncrewed test launch no earlier than April.

The path forward hasn’t been easy: Congressional decisions to delay funding, government shutdowns, and a variety of technical challenges have pushed Boeing and SpaceX two years behind their original schedule. NASA chose a cadre of astronauts to fly on these vehicles; they are currently training and eagerly awaiting their ride past the sky.

Because the world is dependent on Russian Soyuz rockets to access ISS, which can only carry three passengers, the maximum crew aboard ISS is capped at six people. With more frequent trips and larger vehicles expected when US providers come online, the station’s managers hope to keep seven people on station. “That may not seem like a big jump, but statistics tell us that having one more crew member up there can almost double the science and research being done,” said Pat Forrester, NASA’s astronaut office director and a three-time space-shuttle astronaut.

Technical challenges

Koeingsmann and Lueders, the two technical leaders for the commercial crew program, seemed confident after the lengthy pre-flight review process. They congratulated their combined team for coming up with clever operational solutions to design challenges.

For example, when testing in 2018 revealed that the thrusters onboard the Crew Dragon capsule did not perform well in high-heat environments, the engineers came up with a solution involving spinning the spacecraft to face away from the sun and adjusting internal temperatures.

NASA officials admit that the current vehicle won’t meet their standards for flying crew. They are still working through concerns over the parachutes, engines, and a kind of helium bottle used by the Falcon 9 rocket’s propulsion system. That bottle, also called a composite over-wrapped pressure vessel or COPV, was the culprit when a SpaceX rocket caught fire and was destroyed during an engine test in 2016. Since then, the company and the agency have worked to redress the issue, and NASA has asked SpaceX to prove its new COPV system by flying it seven times without issue; so far it, it has flown four times.

Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA’s top human spaceflight official, said last week that NASA will evaluate all the data, but warned that “we’re maybe going to re-design some of these things.”