As a shrinking Japan prepares to open its doors wider to foreigners to tackle the country’s severe worker shortage, the labor crunch is only set to worsen for one profession—Japanese teachers.

The number of foreigners moving to Japan has ballooned in recent years to over 2 million, far outpacing the growth in the number of Japanese language educators. From 2011 (the year of the earthquake and tsunami in northeast Japan) to 2017, the number of students learning Japanese jumped by almost 90%, compared to 27% for teachers, according to Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs.

The trend presents serious problems. Despite Japan’s long-standing aversion to immigration, the number of migrant workers is set to increase at an even faster clip with the implementation of new foreign-worker visas this month. More than 300,000 additional workers could come to the country in the next five years.

A lot of the anxiety expressed in parliament (paywall) and in the pages of newspapers in the leadup has centered on the desire that new arrivals learn Japanese as quickly as possible, to make their arrival less disruptive. In the face of such a serious shortage of Japanese teachers, much of the responsibility for helping newcomers settle in has fallen on the shoulders of volunteers and the elderly. By the agency’s estimate, some 57% of Japanese language teachers in Japan are volunteers, while almost a third are aged 60 or above.

A glimpse of a multicultural Japan

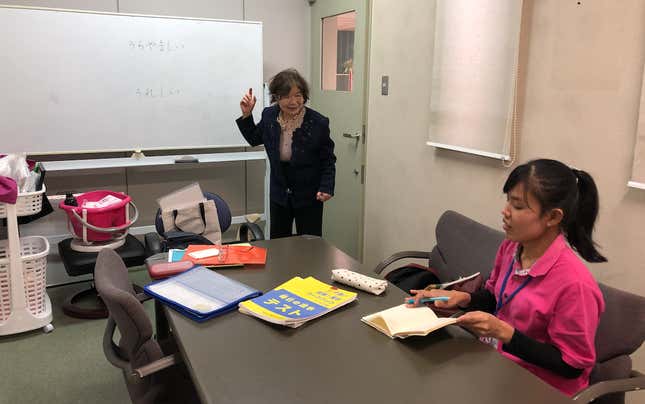

Fumie Uragami ticks both of those boxes.

The diminutive and spirited 78-year-old established the nonprofit Okayama Japanese Center (OJC) in 1984, which provides Japanese lessons to newcomers.

Okayama, which sits between Hiroshima and Osaka, has a population of just over 700,000 and is a major transportation hub connecting western and eastern Japan. Known for its sunny climate and fruit harvests, it is also an important industrial area, with companies including electronics manufacturer Panasonic and car giant Mitsubishi setting up factories there. That has drawn a rapidly growing number of foreign workers to the prefecture.

The most recent government data (pdf in Japanese) count nearly 14,000 foreign workers in Okayama prefecture as of 2017, a 22% jump from the previous year, compared to an 18% increase nationwide (pdf in Japanese). Vietnamese make up the largest share of foreign workers at 37%, their numbers growing rapidly from the previous year. The majority of foreign workers have in the past come to Japan as temporary “trainee interns” at companies—a classification designed to keep the government from having to admit that it is, in fact, opening up the country to foreign workers, and that often led to exploitation.

Uragami arrived at the community center where OJC’s classes are held one recent Saturday, her hands full with carrier bags bursting with snacks and soft drinks. As students filed in to the center, they divided into different groups roughly according to their abilities. One table for total beginners included a father and his two children from Afghanistan who practiced how to sound out and write basic words in hiragana, the phonetic Japanese alphabet. Others were able to discuss their hopes and dreams, such as Kimva Keo, a 21-year-old Cambodian trainee who fries foods at a local supermarket. He told his teacher—Uragami’s son—that he would like to one day return home with the money and knowledge to help his family raise fatter pigs. A student from Pakistan slipped out during the two-hour session for afternoon prayers in a quiet corner.

In one corner of the room in an open-plan kitchen, Uragami taught a group of more advanced students the Japanese word meaning carefree, nonbiri. Without a common language, she resorted to gesticulating, such as acting relaxed while driving in a traffic jam. Some students had an in-built advantage—those who already know Chinese are mostly able to identify meanings from the kanji characters used in Japanese, though one woman from China had difficulty distinguishing the pronunciation between “visa” and “pizza” while learning the Japanese word meaning to apply (shinsei).

Uragami, who has degrees in Japanese and English literature, started teaching Japanese in earnest when she moved to Malaysia for her husband’s job in the late 1970s, where she taught the language to local students at the Japanese consulate. Fueled by her experience living overseas and a resolve to help foreigners settle in the city, she decided to set up the organization in 1984 upon her return to Japan.

“I think that the pace of internationalization in Okayama is still about 10 years behind Tokyo,” said Uragami, who recalls a not-so-distant time when locals would spout racist epithets against dark-skinned foreigners. “However, the number of people working to change that is increasing. After all, society is changing. But I’m still not satisfied.”

In large cities like Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka, where most newcomers to Japan are concentrated, the faces of people from Vietnam, Nepal, and other countries are visible almost everywhere from convenience stories to restaurants to construction sites. In smaller cities or rural areas, however, foreigners are fewer and often out of sight, assembling bento boxes in a kitchen, making industrial parts at a factory, or taking care of the elderly. As a result, support for migrant workers outside of Japan’s metropolises is often sorely lacking. In Okayama prefecture, two-thirds of Japanese-language teachers are volunteers, compared to a third in Tokyo, according to Japan’s cultural affairs agency as of 2017.

As such, companies in Okayama that are dipping their toes into employing foreigners are enlisting the help of the septuagenarian to help their trainee workers settle in, including an elderly home in an Okayama suburb that over a year ago hired its first trainee, a 24-year-old Indonesian caregiver. On Wednesdays, Uragami teaches two Indonesian trainees at a factory belonging to Itano Kikou, a family-owned company that manufactures agricultural-equipment parts. Part of the fees paid by these companies goes toward OJC.

They’re fortunate that their employer pays for their classes and allows them to take time during work to study, said Uragami. “Those who work for ‘black companies’ don’t get this kind of support,” she said, using a term commonly used in Japan to refer to employers that violate workers’ rights.

A longer-term vision for foreign workers

Western countries with long histories of migration and who receive large numbers of refugees—compared to the 42 people who were granted asylum by Japan in 2018—generally have well-organized, government-funded programs assisting newcomers. Canada, for example, provides free language instruction to permanent newcomers and protected persons. Japan, which does not consider migrant workers for the most part as potential long-term residents—let alone future citizens—has no such provisions.

The new immigration law, however, not only paves the way for more workers to enter Japan legally, but even offers some of them the chance to plan a life in Japan in the longer term. A new visa category for skilled industrial workers doesn’t limit the number of times they can renew their visas, and allows them to bring their families to Japan. Other manual and service workers can only stay for up to five years—but some who advance their skills may later qualify for the more liberal visa. Getting the five-year work visa requires passing a test evaluating their Japanese language and skills, which could also increase the demand for Japanese lessons outside of Japan, with the first of these tests held recently in the Philippines.

Adding to that, as some of the workers may later apply to bring their families to Japan or have children in the country, more children will also require education in Japanese. A recent survey conducted by national broadcaster NHK found that of about 120,000 foreign children living in Japan last year, over 8,000 did not attend school.

Iki Tanaka, who works at an NGO-operated school in Tokyo providing language support and other services to immigrants, said it’s unsustainable for the country to continue to relying on volunteers. Not only is it insufficient to deal with the rising number of foreigners in Japan, but the lack of qualifications in teaching Japanese as a second language could also hold back the ability of newcomers to assimilate in Japan.

“Teaching Japanese to natives and teaching it to foreigners is totally different,” said Tanaka. “Not anyone can just teach Japanese.”

To that end, the government said recently that it plans to introduce a nationally recognized accreditation program (paywall) for Japanese teaching by 2020, that would also help make it a specialized, higher paying profession—which could convince more people to teach. And in a move suggesting that Japan is beginning to emulate the practices of other countries that receive migrants on a large scale, the cultural affairs agency announced this month that it plans to implement a standardized Japanese ability index to allow employers and schools to better judge newcomers’ Japanese abilities, modeled on a method of evaluating language proficiency used widely in Europe.

Disappearing students

Organizations like OJC, and volunteers like Uragami, fill an important role in the field of Japanese-language teaching in Japan in the absence of serious funding and regulation by the government. Other providers of Japanese education, however, are exploiting the gap in the market.

Privately run Japanese-language schools have rapidly proliferated in number in the past decade, and some are used as backdoors to enter the country on a student visa and find part-time work. Yasuhiro Idei, a freelance journalist in Tokyo who researches these schools, said that brokers in Vietnam even charge high fees to help enroll people in Japanese schools using falsified bank documents, to the full knowledge of these schools, whose students often mysteriously disappear. Last month, a private Tokyo university said that (paywall) some 700 of its foreign students had been missing for almost a year, in addition to the hundreds who had disappeared in previous years.

Hiroko Yamamoto, the founder of a language school in Tokyo, said that these incidents and the government’s lack of investment in Japanese language education reflect the widespread attitude in Japan that teaching Japanese is just “something that benefits foreigners,” referring to the current approach of language schools as little more than “low-quality cram schools teaching ‘a, e, i, o, u.'”

“If people cannot recognize that the beneficiaries of (greater investment in Japanese teaching) are also Japanese people themselves, then neither side will be happy with the results of the influx of foreigners into Japan,” added Yamamoto.

Meanwhile, Furagami’s workload shows no sign of abating, as she recently started a new job teaching a class of 12 trainee interns from Southeast Asia at a vocational training school four days a week—on top of her two existing paid teaching roles and voluntary role at the OJC. “I’ll do my best,” she said.

Yuzuha Oka contributed reporting.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled the Japanese word for “to apply.” It is “shinsei.”