Last week, when a US Navy destroyer narrowly avoided a collision with a Chinese naval vessel, there was at least something of a protocol in place for the two ships to communicate with one another. The same thing can’t be said of the two countries’ space programs. But that may change with the imminent retirement of US Congressman Frank Wolf, a Virginia Republican who served for 17 years.

Since 2001, Wolf has either led or played an important role on the funding committee for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), where he put the kibosh on any cooperation with China’s space program.

Wolf objected to Chinese political repression and forced abortions due to China’s one-child policy (“Would you have a bilateral program with Stalin?” Wolf once asked). He also feared China might exploit the relationship to gain secret information about US space technology like it did after a failed launch in 1996, as Zach Rosenberg explains.

By blocking any kind of cooperation between the two nations, Wolf’s stand against China contributed to the International Space Station being built without Chinese help. Nonetheless, the US cooperates with Russia on that project and other space initiatives, despite the country’s strategic differences with the US and its tarnished human rights record.

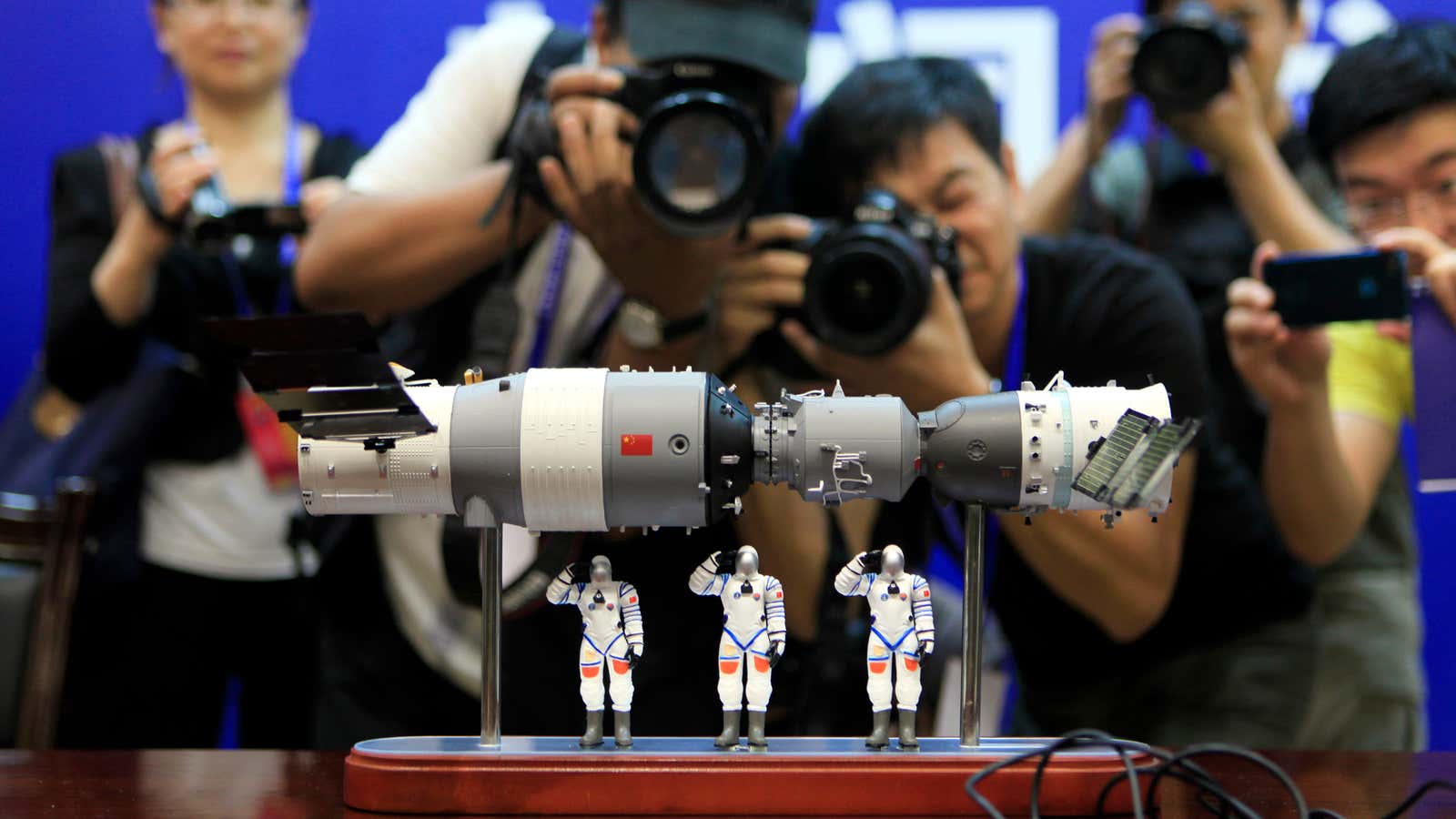

With its attempts to join in the ISS project quashed by Wolf’s ban, China went ahead with its own space station project, launching the Tiangong 1 station in 2011. Since then, it’s been steadily gaining on the Russian space program in terms of both capability and willingness to invest. That’s one reason why Wolf’s replacement might want to consider relaxing his predecessor’s ban on China cooperation, thought it might come with security risks. Experts note that China’s space program is much more tightly intertwined with its military and much more opaque than Russia’s Roscosmos.

But the ban also puts other countries’ space programs in the tricky position of choosing between the US and China, exacerbating international differences in space at a time when more international cooperation is needed.

At the very least, the US should work with China to establish basic protocols for the use of space. That became evident back in 2007, when China’s surprise anti-satellite weapon test sparked international furor after it created a huge cloud of space debris (and the premise for the movie Gravity). But the trust and engagement necessary to avoid similar spats will be hard to build if American and Chinese space experts are barely allowed to talk.