This holiday season, like others in recent memory, we cheered on images of Americans shopping as a sign the economy was back to full potential. It’s striking that no one asked if Americans can afford to spend so much. Chris Giles of the Financial Times argued that because developed economies rely on consumption, more is better. He wished Brits would keep up their holiday spending levels year-round. In America, too, consumption makes up 70% of GDP, so it seems more consumption will mean more growth. According to Paul Krugman we’ve reached a point where “prudence is folly.”

But that’s a short-term view—and it’s dangerous. The key to growth is not getting people to consume as much as possible. Consumption that supports the economy is predictable and smooth throughout people’s lives, not as high as possible in a single year then collapsing when they fall on hard times or retire without any money. For firms to invest more, and create jobs, they need confidence that there will be a market for them next week, next year, and in the long term.

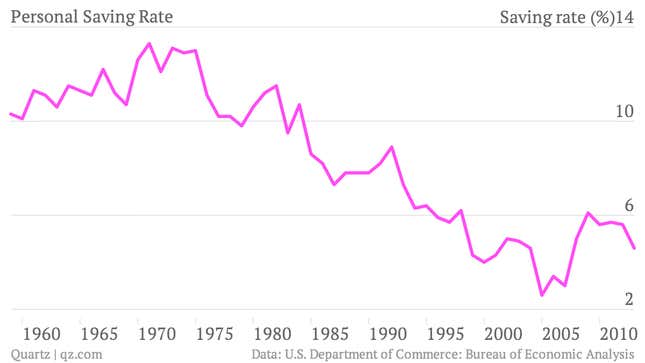

For this to happen, consumers need to save. Since the crisis, they have been repairing their balance sheets, a little. The figure below is the personal saving (saving of households and non-corporations). The saving rate, about 4.8%, is still low by historical standards.

The corollary of low saving is high debt, so it’s not surprising Americans still have lots of it. They may be shifting away from credit card and mortgage debt, due to credit constraints, but they’ve taken on more auto and student loans. Household debt may be lower than it was in 2008, but it’s only fallen to about where it was in 2006.

Rather then lamenting high debt and low consumption, we should fear that people still aren’t saving enough. According to the Urban Institute one-third of Americans are asset poor, meaning an unexpected event like divorce, death illness, even a car break down can mean economic hardship. Many British households are in a similar situation. The economy is weaker and more unstable when it contains many asset-poor households. That’s because if the slightest thing goes wrong, even a small recession, demand collapses as households fall on hard times. That may explain why, according to the IMF, economies with high-debt households experience more severe and prolonged recessions.

Under-saving also contributes to inequality. It is near impossible to get ahead when you live in a financially precarious place. An asset-poor family can’t afford to send their children to college, which increases reliance on student loans and leaves people starting their working lives with heavy debt. Saving puts capital in the hands of middle-income earners. A disturbing trend has emerged lately: higher returns to capital instead of labor. One way to restore equity is to encourage ownership of capital among the middle class.

Boosting demand at all costs may have made sense following the recession. But that should be a short-term policy. As the anemic recovery drags on, when will we finally make savings a priority and restore financial certainty to households?