Chinese stocks did horribly last year. And 2014 doesn’t look much better

When it comes to GDP growth, China beat the bears again. Analysts expect the country grew somewhere in the ballpark of 7.6% in 2013, just slightly down from 2012’s 7.8%. That’s compared with global GDP growth of around 2.9% (including China), according to the International Monetary Fund (pdf, p.2).

When it comes to GDP growth, China beat the bears again. Analysts expect the country grew somewhere in the ballpark of 7.6% in 2013, just slightly down from 2012’s 7.8%. That’s compared with global GDP growth of around 2.9% (including China), according to the International Monetary Fund (pdf, p.2).

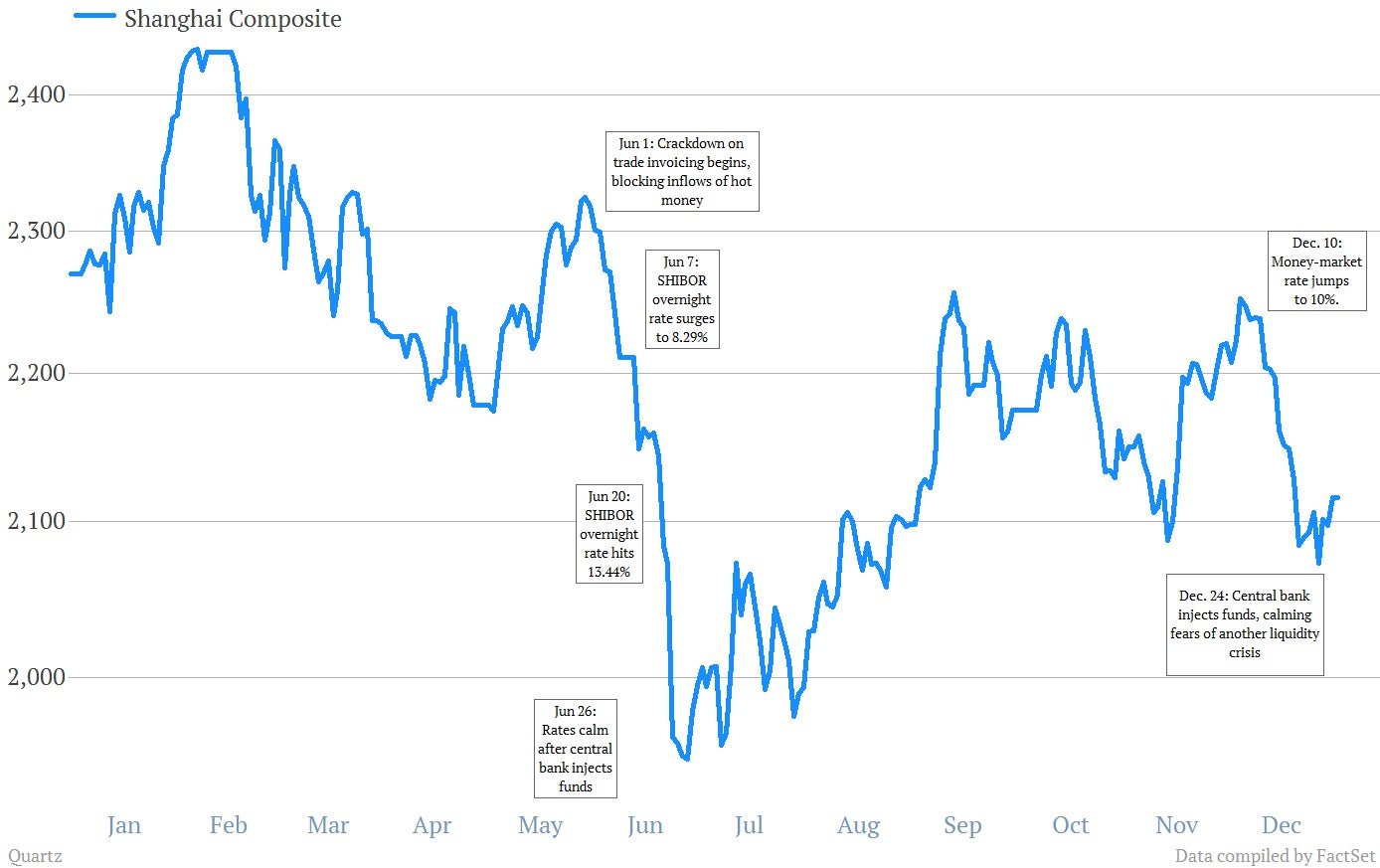

But as China’s economy left nearly everyone else in the world in the dust, its stock market wheezed its way through 2013. The Shanghai Composite’s 6.8% decline made it the biggest dud in Asia:

And that’s just Asia, which, with the exception of Japan, had a lousy year. Compare that with the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index, which surged nearly 30% in 2013:

But what about 2014? Surely it can’t get worse. China’s economy is on track to expand 7.5% next year, according to projections by some economists. And its dismal 2013 means Chinese stocks are “under-valued, under-appreciated and under-owned,” argues Thomas Becket of PSigma investment managers. Desmond Tjiang, a China-focused equities portfolio manager at Pinebridge Investments, argues something similar.

“Overall, we believe Chinese equities are just too cheap to be ignored by investors in 2014,” he told Reuters. ”Despite reforms and the broad economic slowdown, there are still a lot of industries such as mass consumption, e-commerce and environment-related sectors that should continue to grow exponentially in the coming years.”

But there are reasons to be skeptical. First off, the Chinese government has been sitting on IPO applications since October 2012. Limiting the supply of IPOs would in theory boost the market. But China’s recent announcement that it would resume IPO approvals could cause further drops.

Then there’s the fact that the Shanghai Composite has been plagued by liquidity squeezes. The stock market tumbled in both June and December, when cash shortages caused banks to stop lending to each other, upping the risk of defaults.

What we saw in 2013 is that each time the central bank tried to slow the growth of money, the interbank market panicked. That suggests these liquidity dry-ups are likely to increase as the central bank tries to force companies to pay off their debt, as we recently explained.

If liquidity scares are more frequent in 2014, Shanghai shares will have another crummy year. The few international institutional investors who are allowed to invest in Chinese stocks will suffer. But Chinese households, which can’t invest in overseas assets due to government controls, will suffer the most. The country might be growing, but its households are still getting poorer.