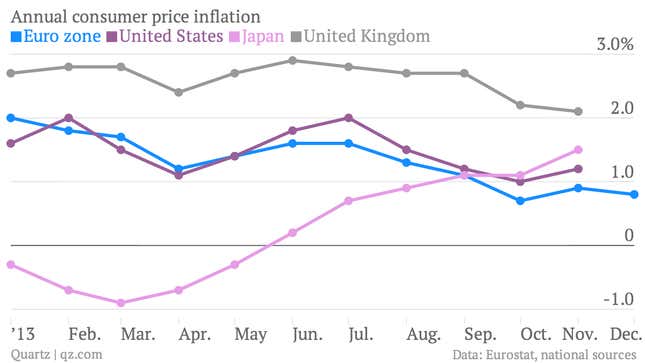

Low inflation continues to sow unease in the euro zone. The latest data, for December (pdf), show consumer prices rising at a 0.8% annual pace, down a bit from the previous month. So-called core inflation, which excludes food and energy, is the lowest it has been (0.7%) since the creation of the euro.

Some fear that steadily falling inflation in the euro zone will eventually slide into outright deflation, as in Japan throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Falling prices are the last thing the euro zone needs, given the pernicious impact of deflation on consumers’ willingness to spend and borrowers’ ability to repay their debts. Like other major central banks, the European Central Bank aims for annual inflation at or around 2%. The euro zone is furthest from achieving this goal of any major economy—including even Japan, which has rebounded in recent months.

Unprecedented economic and monetary stimulus in Japan seems to have pulled it out of its deflationary spiral. Could that happen in Europe? The ECB surprised the markets by cutting interest rates in November after inflation dropped below 1% for the first time since the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis. The bank’s rate-setting committee meets again on Thursday this week (Jan. 9), with some expecting it to unveil further measures to boost the monetary union’s moribund economy.

Analysts at Nordea reckon that the latest inflation results are “low enough for the ECB to remain ready to act, but not low enough to prompt a new rate cut.” This is similar to what many were saying before the surprise November rate cut. Remember, too, that the ECB raised rates twice in 2011 when inflation overshot its 2% target by as much as it is currently undershooting it.

The ECB has not been nearly as aggressive as other major central banks when it comes to combating economic weakness, so it is usually prudent to expect that it will err on the side of caution. But the prospect of Japanese-style stagnation fuelled by deflation may force it to act sooner rather than later—the euro zone is, after all, already halfway through its own ”lost decade.”