If you’ve ordered something smaller than a toaster oven from Amazon in the US northeast, there’s a good chance it may have come from LGA9, a 900,000-square-foot fulfillment center in Edison, New Jersey.

From the outside, LGA9—named, like most Amazon warehouses, after a nearby airport—is deeply unmemorable. It’s one of many, many featureless low-rise warehouses that dot the highways of New Jersey. But through its many loading docks, millions of items are handled each year, from detergent to sports bras, Amazon Echoes to Little Live Scruff-A-Luvs toys, Nature’s Bounty vitamins to Ring doorbells. The facility has 2,000 full-time employees and at its busiest can ship several hundred thousand packages each day.

That efficiency will be called on next week during Prime Day, a two-day retail bacchanal Amazon has been putting on since 2015. This year, Prime Day falls on July 15 and 16, when Amazon and its sellers will put thousands of random products on sale, from steep discounts on all of Amazon’s own gadgets, to 40% off Under Armour clothing, 30% of mattresses, 20% off of Bowflex machines, and preorders of Lady Gaga’s new exclusive cosmetics line. Adding pressure, Amazon recently committed to offering members of its Prime program—a $119-a-year club that provides faster shipping, access to movies and TV shows, discounts at Whole Foods, and more—one-day shipping on many of the products the company sells. It’s a huge ask, and also par for the course: Amazon already upended the e-commerce and logistics industry by making two-day shipping standard for Prime members.

With a veritable World Cup of retail less than a week away, you might expect a sense of foreboding to take hold at LGA9. But general manager Alex Urankar says Prime Day is just another day for them. ”We stay close to peak year-round at this site,” Urankar told me when I visited LGA9 this week.

Thank god for all the robots.

Automation is the key to Amazon’s success

A majority of the average product’s time inside LGA9 is spent in the care of one robot or another. Open since 2017, the building is a prime (heh) example of the extremely automated structure Amazon created to get products from merchants to front doors as quickly as possible.

In older Amazon facilities, products are stocked on endless rows of shelves that employees must walk up and down to pluck items for packing. In LGA9 and many of its newer facilities, the shelves come to the employees.

Amazon uses a combination of old technology, like barcodes, and more cutting-edge innovations, like computer vision, to keep track of its inventory. As a result, the company knows exactly where every product that comes into LGA9 is at all times. It also has different processes for orders that contain a single item and orders that include multiple products housed in the same facility.

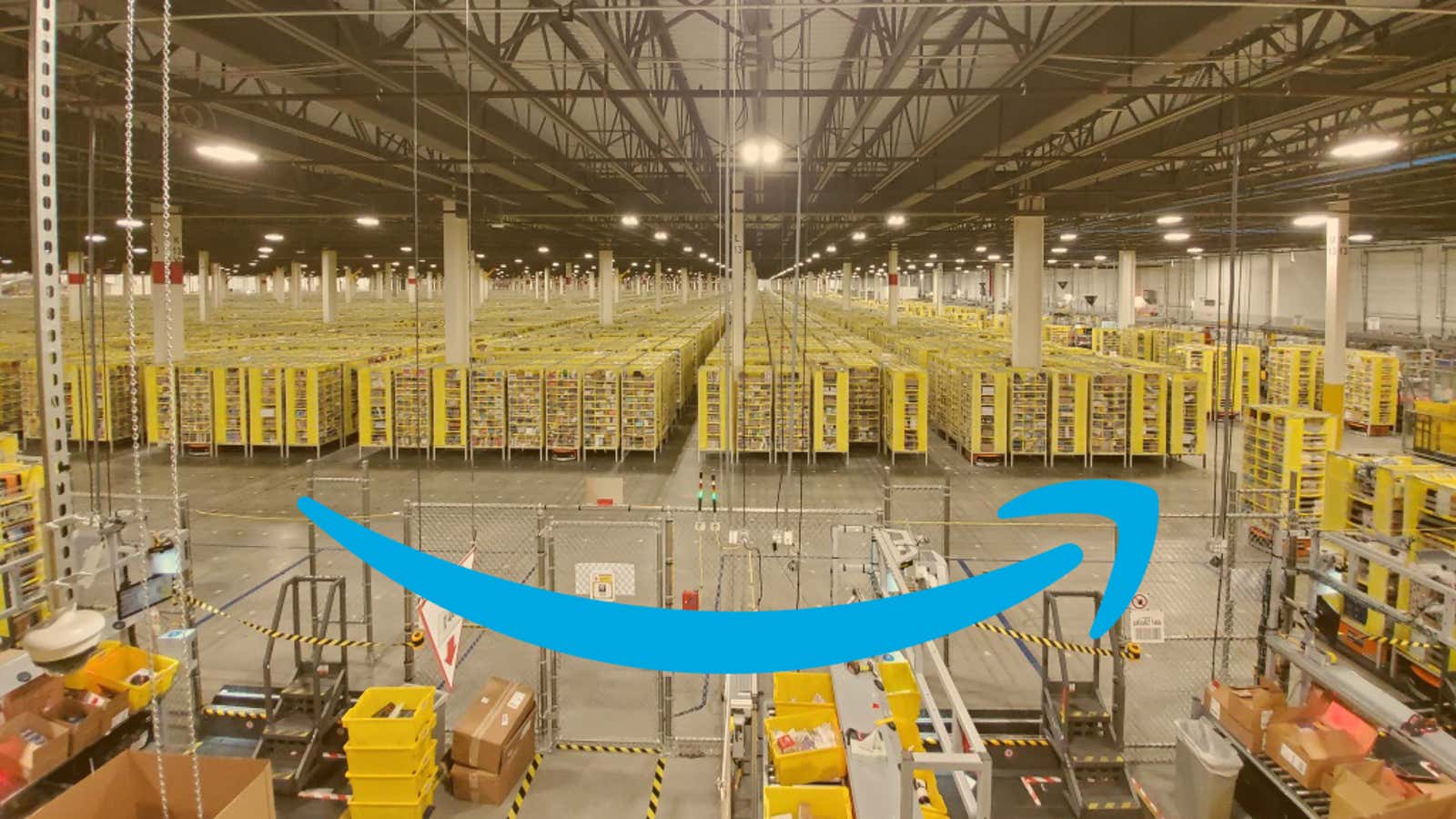

LGA9 is equipped with three vast fields of shelves (the above photo depicts just one) where, barring rare exceptions, no humans are permitted. Beneath the shelves, a tribe of squat, orange robots, descendants of the bots built by Amazon acquisition Kiva Systems, scurry around, picking up the shelving towers on their backs and moving them into deeper storage or ferrying them to the right human.

Human employees at dozens of stations receive towers from the robot field, and plastic bins to sort products into, from an intertwined, super-powered version of the conveyor-belt system you would find in an airport’s luggage-sorting room. A computer in front of the human associate tells them which section within the tower to pull a product from, and which bin to drop it into.

Products are put into the towers at LGA9 in much the same way they’re taken out of them. A worker stands in a workstation, replete with boxes of products from manufacturers, and places them into towers. Scanners at each station monitor which slot each product is put into by following the associate’s hands and identifying each slot in the tower. It’s not unlike the computer vision used in Amazon’s Go stores, but in reverse: Computers are watching people put products on shelves, rather than taking them off.

Once a product has been moved from a tower to a human to an assigned bin, that bin’s barcode is scanned and sent off on the automated conveyer belts to another employee, who packs each product up for shipping.

Packers, like Mariana Rivadeneira (below), receive the bins at their desks, and are told by the computer system which size box and which tape to use for each order. Once a box is packed and taped up, the packer sends the empty bin one way on the conveyer-belt system, and the package another.

“I like to take pride in my work,” says Rivadeneira of packing, which she describes as fun and simple. “I never have to second guess myself.”

At this point in the process, no one who has come in contact with the product knew who it’s for or where it’s headed. The system has tracked everything, but it’s not until the product is packed up and put on another conveyor-belt ride that the package is slapped with a shipping label.

The virtual system that tracks the package through the warehouse scans the barcode on the box and matches it to the order being fulfilled; in a matter of seconds, the package passes underneath another machine that prints the shipping label and affixes it to the package.

The package is then sent onto another specially designed conveyor belt to be packed onto a truck.

The conveyor belts, in conjunction with the facility’s tracking system, send the package to the correct shipping bay. Once it gets to its destination, the package is pushed off the belt on the left or right, and onto a small conveyor that extends into the back of a delivery truck.

Workers are able to slide the conveyor belt back, allowing them to pack the trucks from back to front and avoid lugging heavy boxes too far.

The grim reality of shipping packages

Prime Day will feel de rigueur at LGA9 because it is: A facility accustomed to meeting peak demand has no choice but to become a well-oiled machine. But for all its frenzied activity, LGA9 isn’t exactly teeming with life. There’s a lot of noise and movement, but most of it comes from the robots.

Urankar tries to break up the solitary nature of the work. Employees meet with managers twice during each shift, to stretch and talk through the day’s output goals; Urankar says these check-ins often veer into chatting about recent vacations, weekend plans, and other things that make the team feel more connected on a personal level.

Urankar also hosts small group sessions with employees during their birthday months to solicit feedback on life in the warehouse. He recently implemented one of the suggestions, adding screens by the front entrance that celebrate employees’ accomplishments inside and outside of work. (During my visit, one screen was congratulating a worker on getting a trucking license.) LGA9 also has dress-up days—”Flannel Monday” is coming up soon—and Urankar recently hosted a weekend carnival for associates and their families.

But LGA9 is a relatively new facility; not every Amazon warehouse is as automated, and workers at several fulfillment centers have complained of strenuous quotas, limited bathroom breaks, mandatory holiday shifts, and the need for pain medication (which LGA9 provides for free) to combat the physicality of a 10-hour shift. Amazon also pushes anti-union messages to its managers. There have also been not one, but two, cases of accidental bear-macing at warehouses.

And while Amazon pays its workers well compared to many warehouse facilities—the base associate pay at an Amazon fulfillment center is now $15 per hour, $5 more than New Jersey’s current minimum wage—that’s a relatively new development. The pay hike came after pressure from Vermont senator Bernie Sanders, who introduced a “Stop BEZOS Bill” in September following years of reports of unsafe and grueling working conditions at Amazon warehouses.

On July 15, the first day of Prime Day, employees at a Minnesota fulfillment center plan to stage a six-hour strike to protest the impact on workers of Amazon’s one-day shipping mandate. Employees will urge the company to cut back on productivity quotas they say lead to unsafe working conditions, according to Bloomberg.

Tomorrow’s warehouse

LGA9 seems to represent Amazon’s vision for all of its 110 fulfillment centers and 40 package-sorting facilities worldwide. The building produces over one-fifth of its own energy from solar panels on the roof, and inside Amazon has automated away most of the difficult tasks human warehouse workers faced in the past. Already, it is looking for more efficiencies, including further automating product-picking; other companies are also researching the automation of package-sorting and truck-packing. With autonomous trucks and drone deliveries potentially on the horizon, robots are slowly being baked into every single aspect of the logistics of an Amazon purchase.

Even Amazon acknowledges the impact all that automation could have on its human workers. On July 11, the company announced a pledge to retrain (or ”upskill“)100,000 of its associates for future positions, in anticipation of needing fewer people to run its warehouses. The company is setting aside $700 million by 2025 for the initiative.

For now, the human elements of warehouse work remain very real. Most Amazon associates are on their feet for the majority of their shifts, and injuries remain common (a board near the entrance to LGA9 said there had been nearly 150 injuries this year so far). Even as it works to render more warehouse workers obsolete, Amazon is also trying to improve conditions for those it has. The company offers (relatively) high salaries, generous health insurance, and paid leave—all benefits that helped applications for warehouse jobs double in the last year. Amazon even offers to pay 95% of the tuition costs for associates’ continuing education. The company says about 500 of its employees have gone back to school to learn how to better maintain and work with robots.

There may be a time in the near future where maintaining the robots is the only job still available for a human in Amazon’s warehouses.