A detour to avoid the film set for Hobbs & Shaw was the only reason I happened across this special beach.

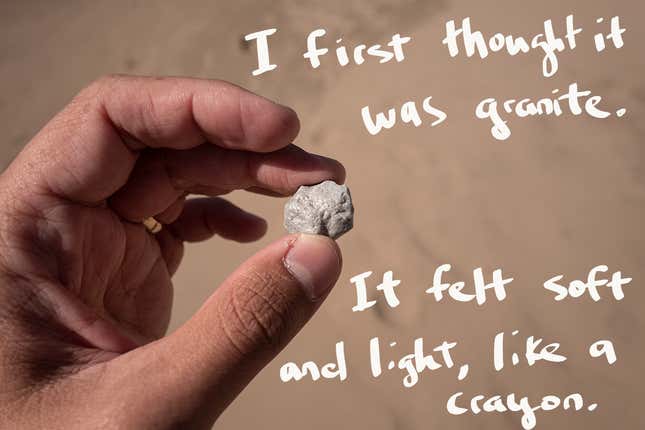

In December 2018, on vacation on Kauai in Hawaii I was following a tip from a co-worker to see giant tortoises sunbathe along the sandy Mahaulepu beach. The shoot forced us to take a different route, which is where I spotted a solitary gray pebble against the pale beige sand. I was struck by how unusual it felt.

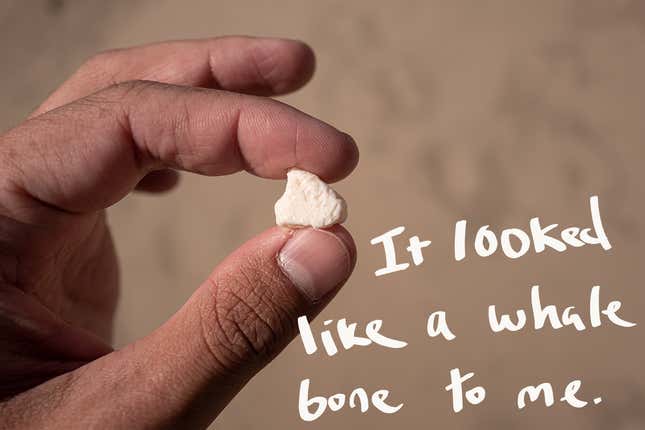

Not too far from the same spot, there was an off-white rock that looked more like a fragment from an animal. Relics like that are common on the Pacific coast beaches where I walk my dog, so I leaned in to pick it up.

Again, I was struck by how it defied my expectations. The object certainly looked like a whale bone, but as soon as my fingers touched it, my skin recognized it as plastic. It was potted and porous like animal remains bleached in the sun. In my hand, its sheen and smoothness more closely resembled the top of a bottle cap than a fragment of a vertebrae.

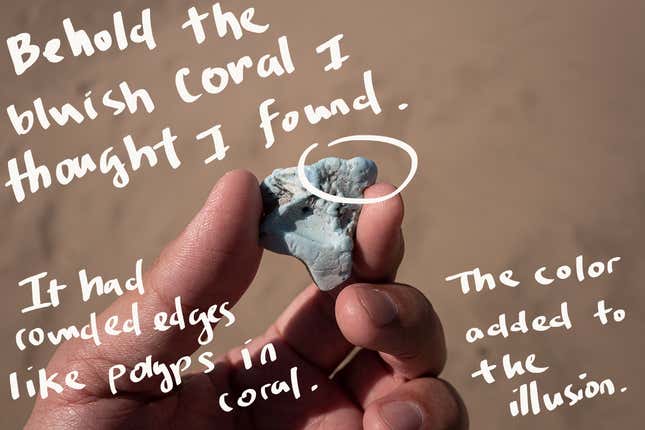

Looking around the beach, the vast number of plastic rocks became apparent. There were many variations. My brain tried to sort the plastic rocks into something that belonged on the beach.

Plastic that’s been melted by thermal vents along the sea floor, forest fires, active lava flow, or campfires are called “plastiglomerates” by geologists. As the material cools it might bond with other debris or rock. The end result can be beautiful other-worldly creations.

The misshapen plastic on the beach could have degraded in other ways. According to Megan Lamson Leatherman, program director at the Hawaii Wildlife Fund, “humans are more in the picture than thermal vents and lava flows.” The physical weathering could be the result of UV radiation. Plastic exposed to the sun breaks down and releases greenhouse gases, while creating ever smaller fragments.

Leatherman also pointed to wildlife as a potential culprit for the faux-rocks. Over 15% of plastic collected by the Hawaii Wildlife Fund’s marine debris recovery efforts had bite marks.

Whether gnawed or super-heated, the plastics wind up in nature, part of our geological record, washing up on our shores.

“The Hawaiian archipelago acts like a sieve,” says Leatherman, “the way that the currents and wind patterns work, the stuff tends to accumulate on our shorelines.” Trade winds and warm water currents deposit tons of plastic waste along once pristine beaches.

This year, volunteers from environmental-protection nonprofit Surfrider have removed 68,308 pounds of plastic waste from Kauai’s beaches.

As curious as these objects may be, scientists already point to the appearance of plastics in this form as a signpost for the beginning of the Anthropocene epoch, an age in which humanity’s imprint on the natural world is indisputable.