In early 2018 I had the opportunity to meet with Lars Heikensten, executive director of the Nobel Foundation. We were at Congreso Futuro, South America’s major science conference, where I shared the aims of transhumanism. Namely, to allow people to overcome death and to live indefinitely through the use of radical science and technology.

Talking with Heikensten got me thinking about the benefits of a global-reaching public prize for longevity. The transhumanist movement currently receives little recognition outside of scientific circles; having an international award like the Nobel prizes would help it spread, to the benefit of all society.

Why shouldn’t we reward efforts and discoveries in longevity with the same accolades we bestow on people who advance other scientific fields, create important bodies of literature, or fight for world peace?

Our societies already reflect an accelerating desire to stop aging. Think of the advances of knowledge, science, and perspectives we could achieve if we had more time and experience. Think of how equipped we would be to fix problems in the future, if we had already lived through the failings and discoveries of past centuries?

The new radicals

As it turns out, I’m not the only one pondering these questions. Earlier this year, I traveled to the Los Angeles headquarters of the XPRIZE Foundation, which awards prizes for “industry-changing technology that brings us closer to a better, safer, more sustainable world.” I had been invited along with about 60 other longevity advocates to help develop a possible prize surrounding longevity. I was ecstatic.

The two-day brainstorming event, hosted by founder Peter Diamandis and opened with a keynote by inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil, was like a historic secret gathering filled with noted longevity scientists planning on conquering death. Among other luminaires in attendance was Sergey Young, creator of the $100 million Longevity Vision Fund. During some of the heated sessions, medical doctors and anti-aging researchers argued loudly across the conference room about biomarkers, enzymes, telomerase endings of genes, and how far mitochondria might be manipulated.

Frankly, I felt a little out of my element—I’m not a scientist, but a communicator. My original proposal, designed later with the help of Max More, Natasha Vita-More, James Strole, and Bernadeane, was called the Longevity Peace Prize. It would award a one-time $5 million prize to a person or a group who convinces a government to publicly classify aging as a disease.

Rising radicals

Radical longevity—also called life extension or anti-aging science—is in the midst of a massive shift. In the last several months, the amount of investment in various longevity-focused products and endeavors has jumped drastically, from millions to many billions of dollars.

In the past year Google upped its investment by $1.5 billion in anti-aging venture with its Calico Life Sciences. This year Bank of America analysts predicted the longevity industry could be worth “at least $600 billion” by 2025.

Gerontologist Aubrey de Grey says we are just a decade or two away from achieving “robust rejuvenation” milestones that will give us treatments to eliminate many diseases, and start to stop aging. Experiments with rodents have already had success with rejuvenating aged organs. Technologists in Silicon Valley are already taking FDA-approved drugs like metformin to make themselves live longer.

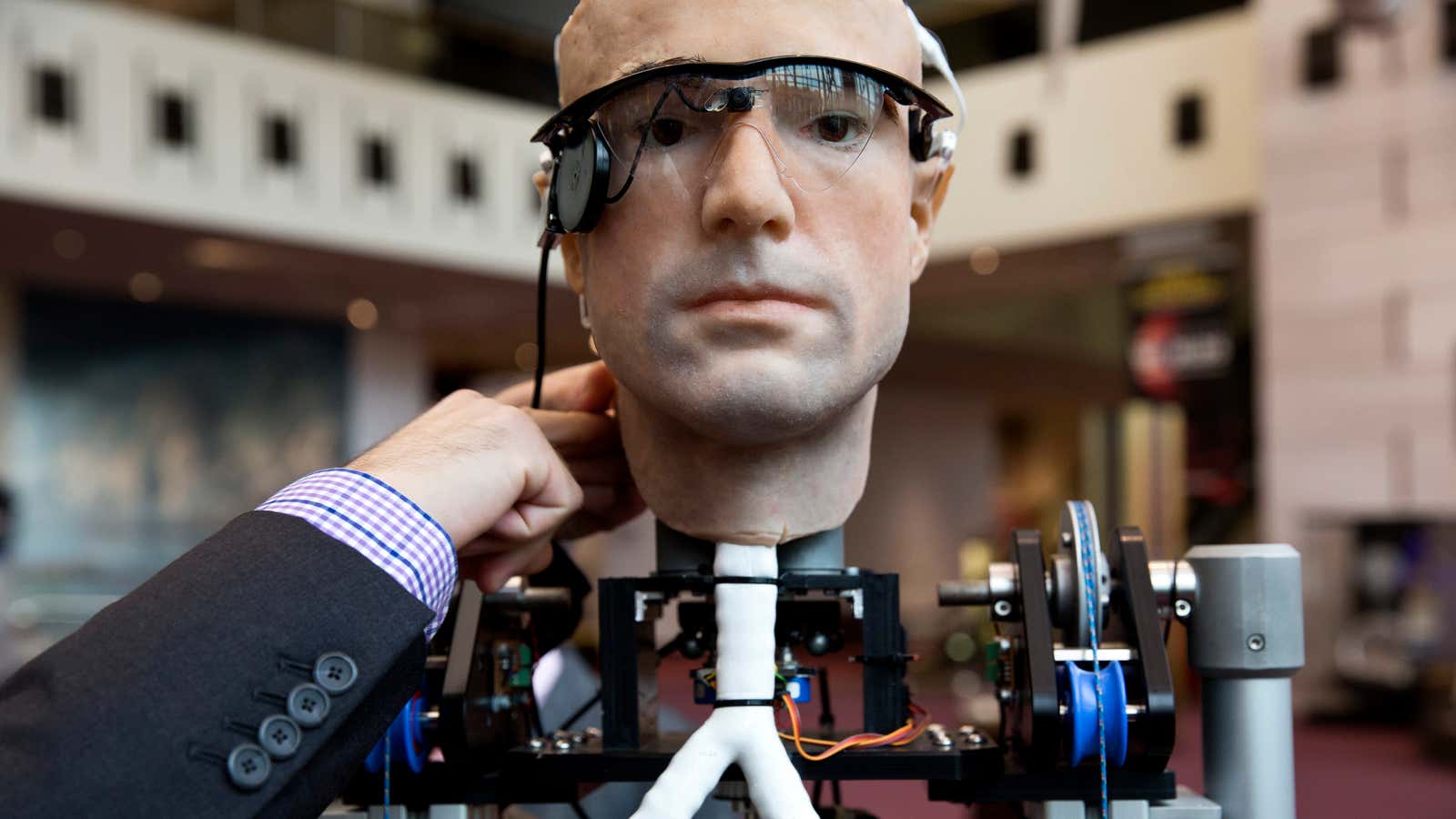

Genetic editing therapy, which can reprogram a gene to not age, is a front runner in anti-aging science. Human experiments are already underway to test the technology. Bionic organs (like artificial hearts) and stem cell therapies are also being developed by dozens of companies designing products to expand healthy lifespans.

Longevity skeptics

In spite of major progress in the scientific community of longevity research—and major resources being invested in the field by leading companies and organizations—many people around the world are unaware that radical life extension research exists as a real thing. Many others are downright skeptical of it.

But the science is already here. And it will inevitably impact how we innovate and solve problems in every major field; from climate science, to politics, to education and health care systems. A major international longevity prize would help societies shift their thinking and become more aware about how deeply the field will alter our future, and how much sooner major shifts will occur than is generally acknowledged.

Historically speaking, prizes targeted at specific issues have garnered a lot of attention, and led to important advances. They also create a public discourse that garners social accountability in a field by improving visibility and allowing more people to weigh in and speak up and participate more in how funding is allocated via awards. The Field’s Medal, awarded to mathematicians under 40 years old, has inspired important changes in math departments around the world. A Pulitzer Prize in journalism often forever changes not only a person’s career, but the power of influence of a person’s work. Even winning an Oscar at the Academy Awards has helped drive cultural trends and changes.

Few goals of humanity could so dramatically alter the lives of humans as extreme longevity. The field is ripe for a significant award. If people start living to the age of 500—which Bill Maris, former head of Google Ventures says is possible—so many current ideas about human life would change, including ones that impact us personally such as marriage, child-rearing, and retirement.

The future is bigger than science (and scientists)

At the XPRIZE Foundation gathering of futurists earlier this year, my Longevity Peace Prize was the only one of the 16 proposals put forth that was based in longevity activism.

The other proposals targeted scientific achievements such as creating specific human longevity biomarkers, targeting dementia with innovative remediation medicine, and carrying 3D printed or stem cell grown hearts around in cryo-boxes for rushed transplants. As these were all heavily science based, they require teams of medical researchers to complete the missions. After a group vote, my award came in eighth and did not make the top-five cut, now being further reviewed by XPRIZE staff for possible award development.

I applaud my science-minded colleagues in the workshop, and I love the amazing work of the XPRIZE. But for longevity culture and awareness to spread around the world, we will need a prize that target audiences outside of the science and medical communities.

Transformative prizes go way beyond their fields; they inspire everyday people to think differently and learn something new about where the world is heading. And just like the Nobel Peace Prize, anybody should be able to win them for doing something important and beneficial for the world, like getting humans to live far longer than they currently do.

Longevity shouldn’t cater to privilege

Much of the world thinks of death as natural, and that to interfere with it would be to spite nature and future generations. For most of the world’s population, there’s also a positive religious implication to death and the opportunity to meet one’s maker.

I have spent much of my professional career trying to tell people why living dramatically longer is essential to humanity. I don’t want to die ever, and I think it’s tragic that individual humans are only here for 80 years or so.

It’s been a long and ongoing battle for me to convince the public that people should try to live far longer. Currently, governments don’t back projects or fund initiatives that consider aging controversial, much less a disease.

And yet billionaire after billionaire is starting to enter the life extension field and invest in it—everyone from Larry Ellison to Peter Theil to Mark Zuckerberg, who recently donated $3 billion dollars to wipe out all disease by the end of the century.

While this is excellent news for the longevity industry, a society that embraces living super long must have more than the one-percenters backing it. It must have the government and national culture supporting it as well. And it needs to be accessible to people no matter who they are.

A high-profile annual global prize for longevity could be just the answer to engaging more people around the world with the developments in the longevity industry. Death and aging impacts everyone, not just the super wealthy, highly-educated populations. Radical longevity should have the same reach, and be available to everyone.

If I could wave a magic wand—and stay within reasonable financial boundaries—I’d create an annual $1 million prize and award it to the person who has had the most positive impact on the public. This award could be for a scientist, a politician, a celebrity, an artist, a philosopher, or just anyone vehemently committed to anti-aging, who creates a true and felt impact in the longevity domain. Importantly, this award committee should focus on longevity pioneers outside of the direct medical or scientific fields.

My visions is for a peace price, not a medical prize, because living indefinitely is not only about aging, it’s also about dealing with our biggest problems, like overpopulation, growing inequality, skyrocketing environmental concerns, and trying to improve living standards for the elderly. Extreme longevity will affect social security burdens, religious beliefs, the health care system, and families who might now regularly have multi-generations living under one roof.

The nuts and bolts

An annual $1 million award would require about a $50 million dollars investment, a small nonprofit foundation to manage the award and its finances, and a good publicity team to organize media attention. There would also need to be a well-planned yearly award ceremony. A $50 million investment may seem like a lot of money, but many one-time donations to universities other non-profit organizations far surpass that.

Isn’t our future, and how it is shaped, a matter that concerns all of us? If we have something like a major longevity award, people can participate in how we adapt to longevity, rather than deal with decisions made in closed meetings and medical labs. If we are to celebrate the work of those who are trying to get humans to live dramatically longer, we need to be a part of the conversation from the start.

I’m still hoping some wealthy patron, organization, university, or government might establish a yearly longevity prize that the world will cheer on. As the future comes closer, people should be aware of what longevity scientists and advocates are working on, and how the specter of death might one day be significantly diminished—whether you like it or not. We all need to be ready for that reality when it arrives.