On Saturday (August 31) in the northeastern state of Assam, in India, authorities published the latest version of the National Register of Citizens (NRC). The list is pretty much what it sounds like—a compilation of names of local residents who are considered Indian. Almost 2 million people, including decorated war veterans and even a state legislator, were not listed and will now have to quickly prove their citizenship or risk detention.

Residents could learn their status, whether included on the NRC or excluded, by checking the register’s website or at local help centers. However, the NRC website crashed soon after the list was published, though it appears to be back online now.

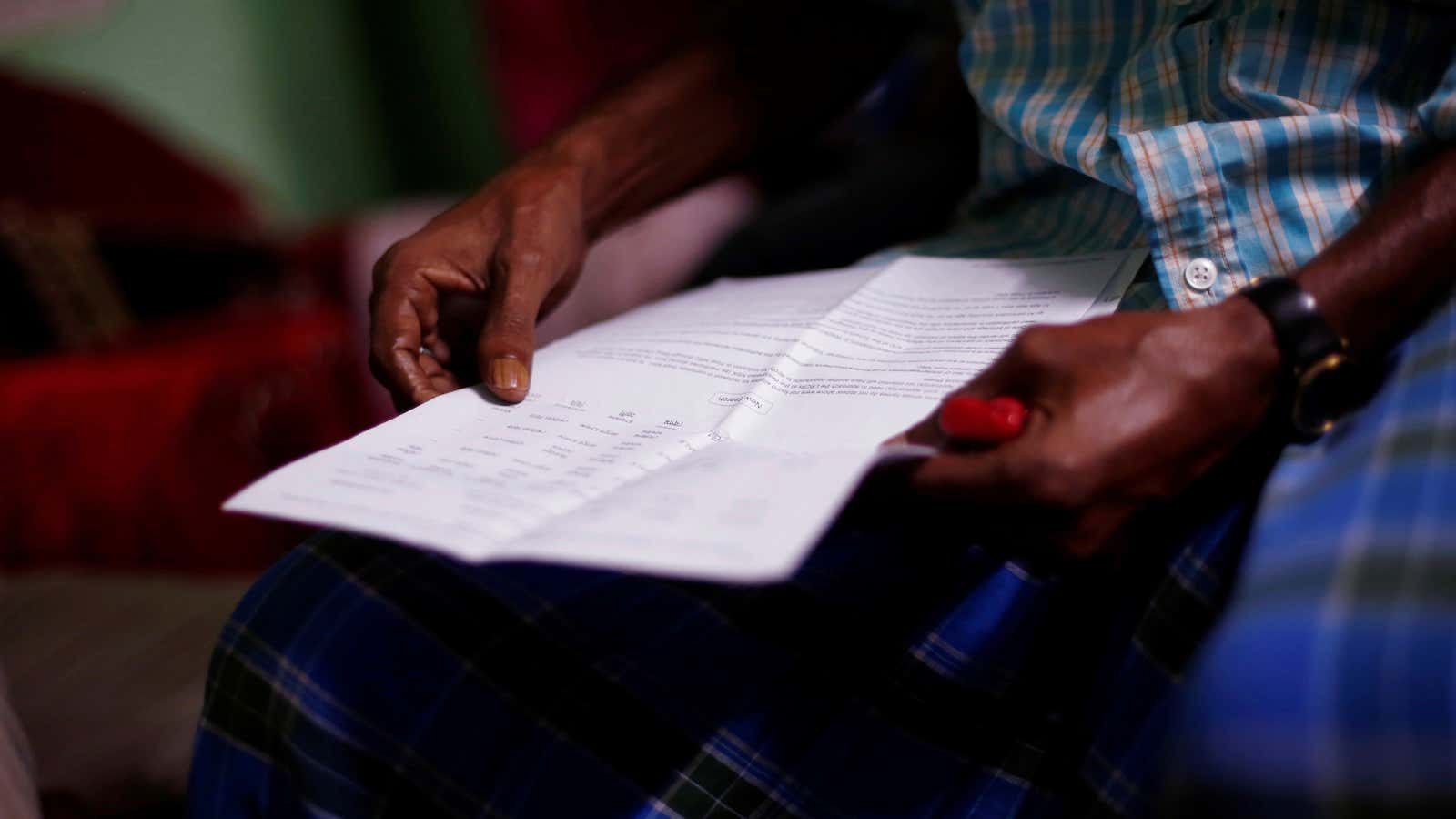

To demonstrate they belonged on the register, residents had to show that they or their forebears were in India before 1971. The controversial list is unique to the state of Assam, which neighbors Bangladesh (though there’s been some talk of implementing it nationwide). It’s been in existence since 1951 and, some say, is not just aimed at migration, as stated by authorities, but is also intended to target the Muslim minority, which makes up a third of the local population.

Whatever the real reason for the NRC, there is no doubt that its publication has in the past caused chaos and is doing so again today. A draft version of the list, published in July, left off 4 million local residents. The latest version includes 31.1 million and leaves more than 1.9 million people in Assam with no state and very little time to show authorities they should not be detained.

Those excluded from the NRC have 120 days to prove their citizenship at so-called “foreigner’s tribunals,” which Al Jazeera describes as “regional quasi-judicial bodies.” There are currently 100 such tribunals in existence and authorities plan to rapidly add 200 more to deal with the expected flood of citizenship review requests. These courts for foreigners then have six months to make a final determination as to individuals’ citizenship.

Assam residents who are ultimately unable to prove that they meet the register’s requirements may be held in detention centers or face deportation, in addition to losing the right to vote locally and being deprived of other civil liberties, human rights activists say. However, Indian television outlet NDTV reports that local authorities are promising that everyone will have a fair hearing and that no one will be officially declared a foreigner until all legal options are exhausted. “Any person who is not satisfied with the outcome of the claims and objections can file an appeal before the foreigners’ tribunals,” NRC coordinator Prateek Hajela said in a statement.

This is surely a small consolation to the many who now must try to show they belong in Assam specifically and in India generally. Authorities are aware of this, if the heightened security in the region is any indication. Tens of thousands of paramilitary personnel and police are posted across the state in anticipation of potential problems resulting from the list’s publication. Any gathering of more than four people at some public places in sensitive areas with a history of violence, including Assam’s main city Guwahati, is banned.