From dial-up to 5G: a complete guide to logging on to the internet

The world would not be what it has become today without the internet. It touches just about every aspect of how we live, work, socialize, shop, and play. But access to the internet is a recent phenomenon that’s reshaped the world in a stunningly short amount of time. In just a few decades, the internet has gone from a novel way for the US military to keep in touch to the always-connected heartbeat of the human race. With each passing year, more and more people have gained access to the internet—here’s how they’ve logged on.

The world would not be what it has become today without the internet. It touches just about every aspect of how we live, work, socialize, shop, and play. But access to the internet is a recent phenomenon that’s reshaped the world in a stunningly short amount of time. In just a few decades, the internet has gone from a novel way for the US military to keep in touch to the always-connected heartbeat of the human race. With each passing year, more and more people have gained access to the internet—here’s how they’ve logged on.

The earliest days

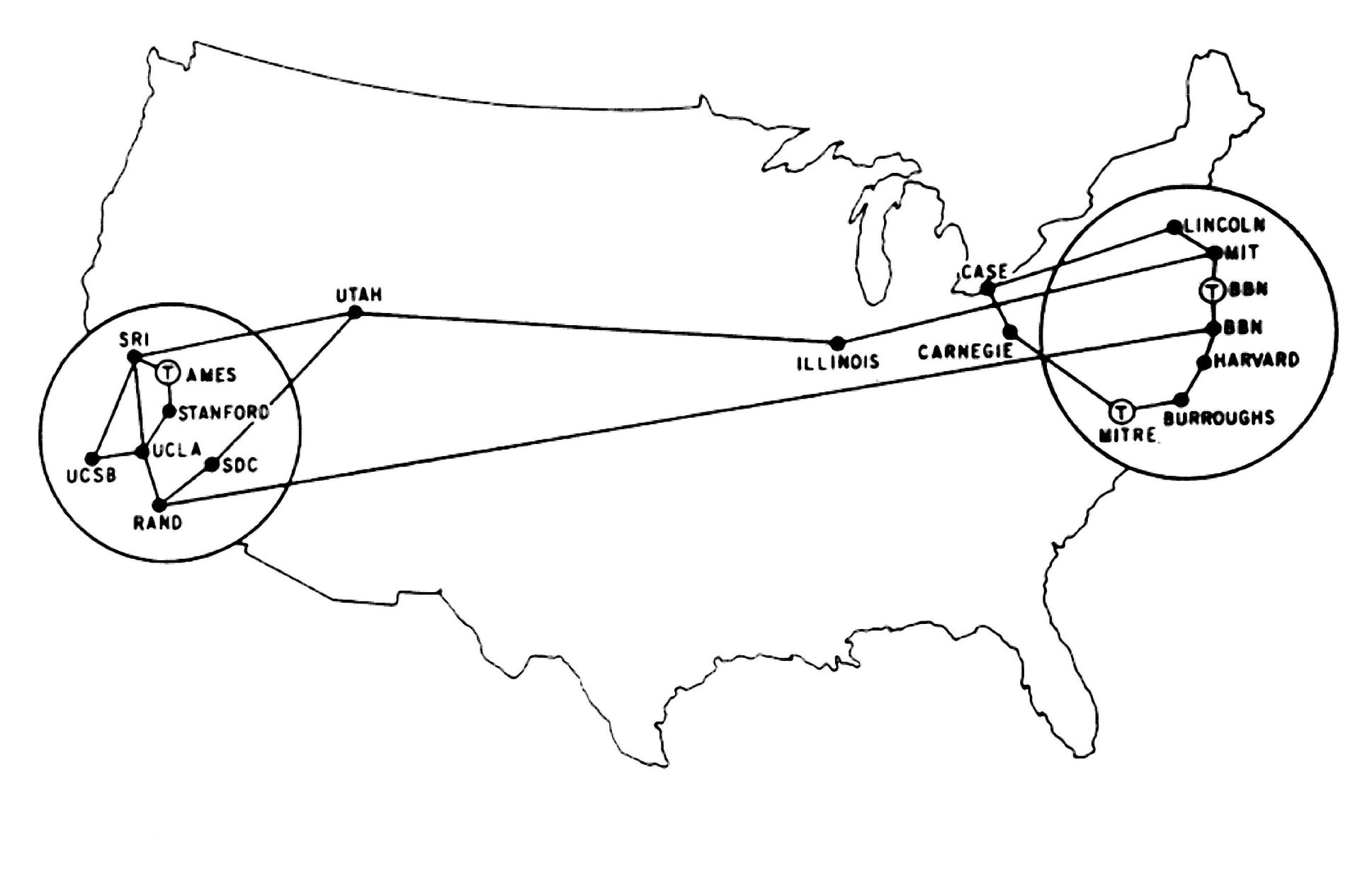

The internet traces its roots to a US defense department project in the 1960s born out of (pdf) the Cold War, and a desire to have armed forces communicate over a connected, distributed network. The military’s research arm, the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), began work on a communication project, which led to the creation of ARPANET, one of the earliest iterations of computers talking to each other on a network. ARPANET eventually connected military installations, third-party contractors, and a handful of universities in the US. By the mid-1970s, ARPANET had connected to NORSAR, a US-Norwegian system designed to monitor seismic activity from earthquakes or nuclear blasts, over satellite. The Norwegian system then connected to computers in London, and eventually, other parts of Europe.

The computers used to connect this nascent network together were gargantuan by today’s standards. The SDS Sigma 7, which cost $700,000 in the mid-1960s ($4.8 million in today’s dollars) was used by the University of California, Los Angeles to send the first message over ARPANET to Stanford University. SDS, or Scientific Data Systems, an early US computer company staffed by Packard Bell alums, built that first computer that connected to the network. The machine, like its offspring that helped the first people land on the Moon, was not like the computer we know today: It took up a large portion of the room it was in and consisted of a series of cabinets with reel-to-reel tapes, flashing buttons, and toggle switches. There would’ve been a small station with a keyboard and a very basic monitor, but much of the data for the machine would’ve been stored on punch cards. The first message sent was the word “lo;” the researchers were trying to type the word “login” and the system crashed after two letters. (Remember that next time Facebook goes down for a few minutes.)

In the early days, these systems used Interface Message Processors (IMPs), which were computers designed to organize and receive the data coming in and out of the network. Essentially, they were the earliest versions of the modern router. ARPANET relied on leased telephone lines, much like the commercial internet did in the years that followed. Around the same time, computer scientist Ray Tomlinson, working at the research firm Bolt, Beranek and Newman (now part of Raytheon), created the original version of email; then-Stanford professor and future “father of the internet” Vint Cerf coined the term “internet” to talk about this growing network of interconnected computers.

Over the 1980s, a grant from the US National Science Foundation allowed smaller universities to connect to ARPANET to share information with those who couldn’t directly connect to the network. By the late-1980s, schools in around 25 countries had connected to the network—in 1983, the US military was given its own branch of ARPANET, called MILNET, for secure communications, allowing other research and communication to take place on ARPANET.

Dial-up

The earliest days of the consumer internet were soundtracked by a cacophony of digital hisses and beeps.

As internet protocols and technologies were standardized, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, universities, businesses, and even regular people started to connect over the internet. But before the invention of the World Wide Web, accomplishing anything was a real chore. Information on the internet was difficult to search for, and almost impossibly dense. “The pre-Web Internet was an almost entirely text-based world,” ZDNet editor Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols said on the 20th anniversary of the site in 2011. “If this makes the pre-Web sound like a place that was only welcoming to techies in those days, you’re right, it was.”

We may not have moved beyond the internet of the early 1990s were it not for Tim Berners-Lee, who was looking for an easier way to find and share research. Berners-Lee, who in 1989 was a researcher working at CERN, the Swiss nuclear research facility, came up with the concept of the World Wide Web, a decentralized repository of information, linked together and shareable with anyone who could connect to it. He built the first webpage in 1993. Seeing the value in what Berners-Lee and his team had created, CERN opened up the software for the web to the public domain, meaning anyone could use it and build upon it.

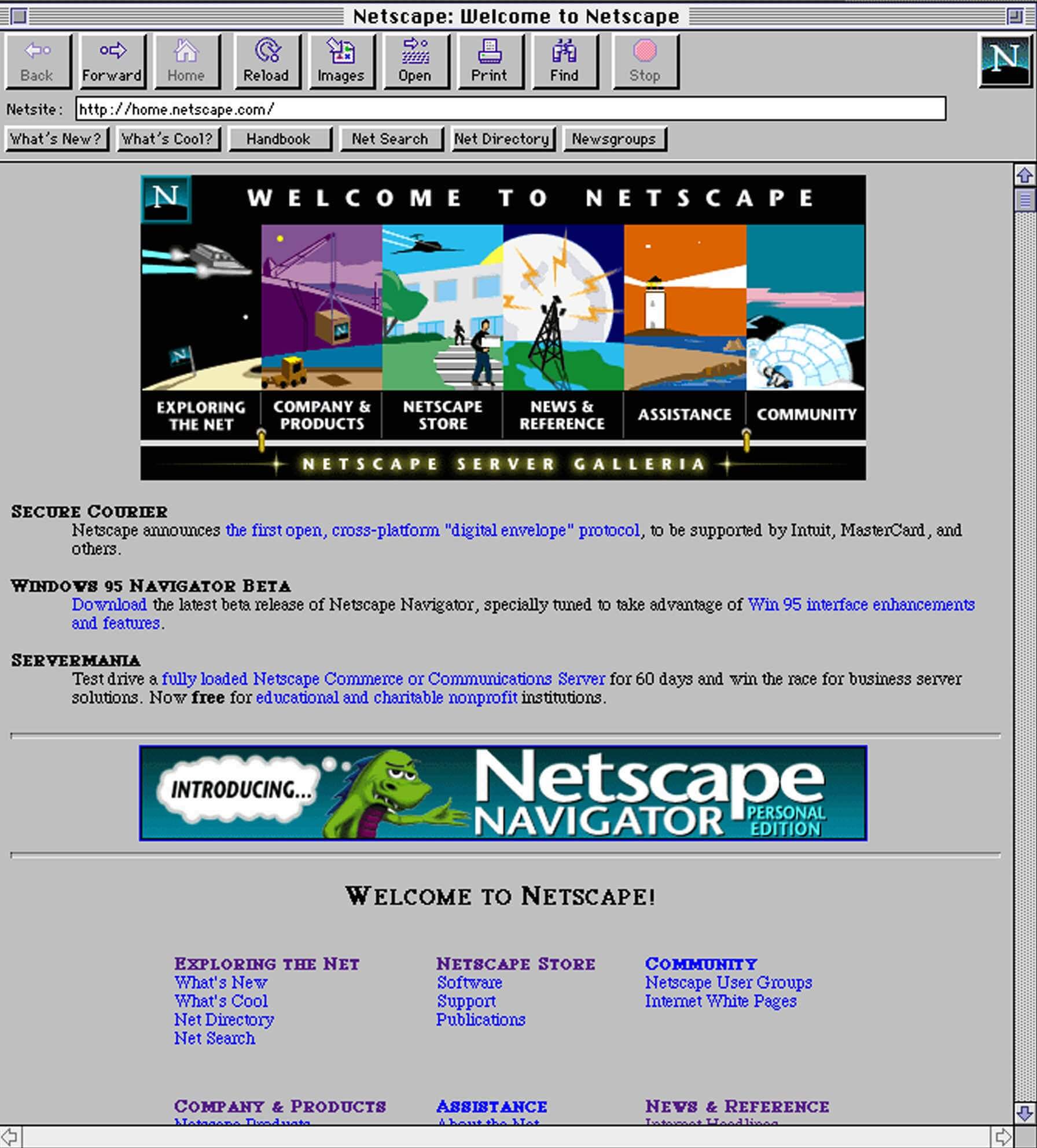

Berners-Lee also created the first website browser (initially called WorldWideWeb and then renamed Nexus). But it wasn’t until a team of former students at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign (UIUC), led by Marc Andreessen, created the Mosaic web browser in 1993 that the web started to take off. Andreessen and his team left the research facility at UIUC to start Netscape, the company that produced the first web browser many people ever used: Netscape Navigator.

By the mid-1990s, Netscape had about 80% of the browser market in the US and Europe. Its only real competitor was Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, which first launched with Windows 95. But Microsoft, a huge company even then, was able to iterate its software faster as the web changed, implementing new technologies like CSS (cascading style sheets—the code that ensures the web is more than just bland pages of text) before Netscape could. (Microsoft’s dominance remained pretty much unchallenged until the dawn of the mobile web, but more on that later.)

At the time, internet services, especially in the US, started to become more affordable. Although the first phone modem was invented in 1958 by Bell, which could just send data to other Bell devices, the first modem designed to use with a PC didn’t arrive until 1977. But it wasn’t until 1996 that we got the 56k modem, which let internet users surf the web at a blistering 56,000 bits per second. (Today we can download a 1 GB file in about 32 seconds, compared with around 3.5 days, which is what it would take on a 56k modem.)

Internet service providers like America Online, Prodigy, Earthlink, and CompuServe, dominated early access in the US. Subscribers would almost always rely on their existing phone line for connection to the internet, meaning that no one could use the phone when someone was on internet. And everyone connecting in the mid-90s through to the mid-2000s likely knew of the horror that was the dial-up modem connection sound.

Broadband

At some point in 2004, for the first time ever, there were more people in the US who had access to broadband internet than dial-up, according to the Pew Research Center. The price of broadband connections had begun to fall as more users signed up. Broadband modems act a little differently than their dial-up predecessors in that they do not need to call out over the phone line to your internet service provider to establish a connection to the internet—they stay connected unless they’re turned off. In the US today, most broadband connections come into homes through the same connections used for cable TV, and don’t tend to require access to a telephone line to connect.

Coupled with the advent of wifi, broadband has revolutionized the way that people connect to the internet. Before wifi and broadband, accessing the internet was a very static and slow experience, requiring someone to sit in front of a large computer, physically connected to a modem, to access the web. But when wifi started to gain popularity, it made the internet accessible wherever someone had a laptop, tablet, or Palm Pilot and wifi connection. The earliest versions of wifi were implemented in the mid-1990s, but it wasn’t until Apple included the technology in the iBook laptop in 1999, as well as other models in the early 2000s, that it really started to kick off.

Broadband speeds are generally faster than dial-up. In the US, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) considers a broadband connection—at least for a fixed line, rather than a cellular connection—one that can achieve speeds of 25 Mbps for downloads and 3 Mbps for uploads. This could certainly change in the future—the definition has changed in the past—but for now, it accurately portrays what most of the country has access to.

These speeds helped make the internet what it has become: in the early web years, loading web pages even with simple graphics could take several minutes. With higher speeds, websites could load faster, and developers could add more content to their sites without fear that it would crash their user’s computers. Even streaming videos became possible; YouTube first launched in 2005. Websites evolved from simple destinations to interactive places where people could buy things and communicate with each other in real-time.

That being said, there are still some 19 million people in the US who don’t have access to the internet at all, and roughly 43% of the world’s population is also without access. But there are many efforts to bring internet access to those where fixed connections are difficult to deploy. Cable companies are using old broadcasting radio frequencies to deliver high-speed internet, and autonomous balloons can beam internet down to even the most remote locations. As access to affordable wireless technology broadens, and our concept of the internet continues to shift, it’s likely the number of people not online will drop rapidly over the next decade.

Cellular data

If you thought the advent of broadband and the internet as we know it today came quickly, you’re going to be blindsided by what happens in the next few years.

Mobile broadband—connecting to the internet through a cell phone—has exploded in popularity over the last five years. At the end of 2013, there were about 1.9 billion smartphone subscriptions in the world, and by the end of 2018, there were about 5.3 billion—that’s a jump of about 180% in five years.

Smartphones are getting cheaper—the global average price for a phone is around $368, but there are dozens of smartphones that will get the job done for less than $50—and access is improving every day.

It’s a far cry from the earliest iterations of the mobile internet, like WAP (Wireless Application Protocol). Introduced in 1999 and seen in such phones as the Nokia 7110 (which many incorrectly associate with being featured in the year’s smash-hit film The Matrix), WAP was sort of like the early dial-up of mobile internet. You could look at rudimentary pages of the internet, to check things like sports scores or news headlines. But getting too deep into the internet would likely burn through whatever overpriced data plan you had at the time.

The first truly useful mobile data standard was 3G in 2003, when radio technology first allowed for more than calls and texts to be sent over the air. (In the western world in 2019, it’s often the connection type your smartphone will fall back to when it can’t connect to LTE; in other countries, it’s still the standard.)

The mobile web truly took off with the iPhone, however, and all the devices that aimed to copy it. When introducing the iPhone, Apple founder Steve Jobs said it was taking on the role of three devices at once: “It’s an iPod, a phone, and an internet communicator.”

The iPhone was first launched in 2007 (though a 3G model wasn’t introduced until 2008). Over the last decade, Apple has sold more than 1 billion iPhones and spurred on competitors like Google, whose Android operating system is now installed on over 2 billion devices. Suddenly, a device that fit in the palm of your hand could access the web in (more or less) the same way as a laptop. The mobile web has created an entirely new economy—Apple estimates that developers have generated $120 billion in revenue from apps developed for the iPhone and iPad since Apple’s App Store was first introduced in 2008. What’s more, we now spend an average of fours hours every day on our phones, much of that time going to social media.

According to a recent consumer report (pdf) commissioned by networking hardware company Ericsson, the average smartphone owner in the US currently uses around 8GB of data each month. The company expects that number to balloon up to possibly 200GB per month by 2025. Mobile devices will likely not look like they do now: In the same way using a smartphone to access the web in 2019 is nothing like using a laptop to get online in 2003, or a desktop in 1993, it’s possible a completely new paradigm will be invented for our super-fast, mobile future. The future of the web will likely be increasingly mobile, but probably won’t be dominated by the devices of today.

As 5G wireless networks are deployed around the world today, many with the promise of download speeds over 1 Gigabit per second (compared to LTE, which maxes out at around 25 Mbps in the US), and connections so airtight it’ll feel like you’re in the same room as someone thousands of miles away. It’s easy to see how the internet could progress from its simple roots, but not what form it will take.

It’s possible that the next iteration of the internet, powered by 5G, could introduce some fantastical-sounding scenarios: surgeries performed remotely in real time; fleets of autonomous trucks all monitored from afar; augmented reality glasses that overlay holographic information in front of us as we move through the world; computers hosted in the cloud.

But for now, these are still pipe dreams. While the new networking technology is being rolled out, adoption for the expensive networks will likely be slow, and there’s no guarantee that real-world infrastructure will ever live up to the promise of what engineers can pull off in a lab. But then, people probably said the same things about those early messages pinging back and forth from UCLA in the early 1970s.