Law enforcement suicides in the United States have surpassed line of duty deaths in recent years. There have been 14 reported police suicides this month alone.

And for every police suicide, there are at least 1,000 police officers with post-traumatic stress, according to Badge of Life, a nonprofit focused on police suicide prevention. Unlike physical injuries, mental trauma for cops occurs “almost daily,” creating risk for the officers themselves as well as those with whom they interact.

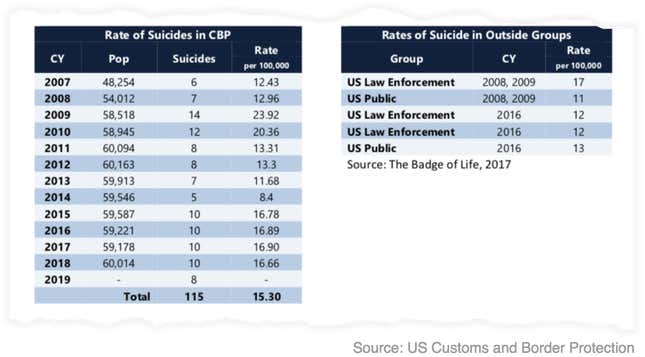

In no department or agency is this mental health crisis more acute than at US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and its Border Patrol division. According to an internal government report obtained exclusively by Quartz, the rate of suicide at CBP is almost 28% higher than at any other law enforcement agency. From 2007 through Sept, 11, 2019, 115 CBP employees have died by suicide.

Yet, in the face of this growing problem, sources with knowledge of CBP’s efforts to address mental health told Quartz that the agency isn’t doing enough and, in fact, has fostered a culture where seeking help is not only discouraged but punished. This is worrying for both the officers the agency employs, and the often vulnerable migrants with whom those officers are required to interact.

An unqualified response

Jenn Budd, who served as a senior Border Patrol agent from 1995 to 2001 and now works as an advocate for immigrant’s rights, doesn’t believe the spike in mental health problems at the agency is the result of the increased workload required by US president Donald Trump’s “zero tolerance” immigration policies. Rather, she said, it is likely the new tasks officers and agents are now being asked to perform that are adding to the existing stress of the job.

“Agents who are being forced to work in the processing centers where they’re holding asylum seekers for weeks, if not months, in these conditions…even if the agents think it’s okay, they don’t realize it’s affecting their mental health,” Budd told Quartz. “And certainly in those cases where people die while they’re on duty, they may sit there and say, ‘Well, it’s not my fault, it’s not my fault.’ But you know that internally, it’s affecting them.”

Even for those who do recognize the strain the job is having on their mental health, there are said to be few avenues for seeking advice and the department is doing little to either make quality information or appropriate professional help available.

CBP says it employs staff psychologists in its human resources division who support a broad portfolio of programs. But instead of deploying clinical mental health professionals to the field, for example, CBP and Border Patrol rely heavily on peer counselors drawn from their own ranks. These counselors are given minimal training by outside contractors and then sent back to their sectors and stations “like they’re professionals,” Budd said.

“I can say as somebody who’s gone through it, you need professional help when it gets to [the point of suicide],” she added. “You don’t need some agent who had 8 to 40 hours of sitting in a class, learning the common causes of suicide and how to tell people to look on the brighter side. It’s just not right. It’s not going to cut it.”

A chaplaincy program for border officers launched in the early-2000s is similarly anemic. A source with knowledge of the situation said the chaplains are not full-time clergy with advanced degrees, but full-time officers and agents who perform lay faith-based counseling in addition to their regular law enforcement duties. The source said that at Border Patrol, a chaplain is only required to attend a brief course and is not required to have a Masters of Divinity like professional chaplains at other agencies.

Past suicide prevention programs organized by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), CBP’s parent agency, have also not been particularly successful. A 2009 effort called “DHSTogether” went without “a formal vision or set of goals” for its first four years. In 2012, DHS hired a government-run service to create a peer support program for DHSTogether. However, a 2013 report commissioned by DHS said the partnership accomplished little.

DHS earmarked about $1.5 million for DHSTogether, before reducing that funding to about $1 million for the 2014 fiscal year. “Because of the modest funding, few or no resources are tied to the policies that are promulgated by the program,” the report said. The most recent mention of DHSTogether on the DHS website is a list of agency-specific resources, last updated in 2015. The CBP resource list links to a website that does not load, and lists a phone number for a peer support program that is no longer in operation. A message Quartz sent to the email address listed for the program was never returned.

Last year, CBP hired a private company that operates employee assistance programs. But the one-year pilot ended before the company managed to recruit someone to run it.

In response to Quartz’s earlier inquiries, a CBP spokesperson said the agency had “expanded” its resources to prevent suicide, and has held events both during Suicide Awareness Month and at other times that can be live streamed and viewed throughout the year. The spokesperson also said the agency has a peer support program, a “robust” Employee Assistance Program, and “an agency-wide” internal website dedicated to suicide prevention, which includes suicide prevention videos.

Not meeting basic standards

Part of the problem, Budd and others say, is that—unlike virtually every other federal law enforcement agency and many state and local police departments—new recruits at CBP aren’t given psychological evaluations or personality assessments.

Police psychologist Marla Friedman has said that it is necessary to implement pre-employment evaluations to determine the “mental elasticity” of new recruits, and their attitudes toward maintaining health regardless of “perceived stigma.”

“The goal would be to narrow the selection process to specific candidates who demonstrated mental flexibility and the willingness to undergo ongoing mental health checks and/or treatment to maintain and develop personally and professionally, without regard to the stigma of engaging in therapy as needed,” according to Friedman.

James Tomsheck, CBP’s chief of internal affairs from 2006 to 2014, told Quartz he lobbied for years to add independent psychological screening to the hiring process. Tomsheck said he went through a battery of psychological tests and evaluations to become a police officer in his hometown of Omaha, and did the same to become a US Secret Service agent, a job he held for 23 years. But at CBP, he explained, “accounting said it was too expensive and the leadership said it would add too much time to the hiring process, another layer.”

In an email, a CBP spokesperson said, “All candidates who apply for Border Patrol Agent and CBP Officer positions attend a medical examination. If any issue is identified that may affect safe and efficient job performance, the applicant is given an opportunity to provide additional information. For applicants who have mental health follow-up, this information is reviewed by a forensic psychiatrist to provide a medical recommendation to make a medical qualification determination.”

A culture of silence

While limited psychological support services exist for officers and agents at CBP, taking part in the few opportunities that do exist is also taboo, Budd said.

“Once you’re labeled, your career is over,” she said. “People are ashamed to ask for help. It’s not a badge of courage to say, ‘I’m having troubles. I’m having problems.’ It will affect your promotional ability. It’ll affect whether or not you get [special assignments]. So nobody will ever come out and say things like that.”

In fact, as James Phelps, a professor of criminal justice who studies border enforcement, told Quartz, many border officers have actually been told by supervisors that anyone who makes use of the available psychological support services is a failure. Further, he said the long, unpredictable hours make it hard to schedule counseling appointments. The Border Patrol tells prospective applicants that 16-hour days “are not that uncommon,” which is true for all CBP officers.

“You’re literally walking out of the shift room, getting in a pickup truck or an SUV and driving 50, 60 miles to your observation post,” Phelps said. “By the time your shift ends, you have to stay there and wait for the relief shift to show up. And if the relief shift doesn’t show up, you’re stuck.”

While some observers have suggested border officers just quit, that isn’t always an option, especially for someone with a family. And, Budd pointed out, joining another agency becomes impossible for anyone over a certain age. New hires at the FBI, for instance, must be younger than 37.

The more obvious solution would be to invest more in the mental health of immigration officers, especially those working along the southern border, where they are often the first Americans with whom migrants interact.

Christian Penichet-Paul, policy and advocacy manager at the nonprofit National Immigration Forum, called on the Trump administration—which is spending somewhere between $25 million and $1 billion for each mile of border wall—to redirect some of that money toward proper counseling and other psychological support services for border officers.

“The cost of building just one mile of physical barriers could help pay for better services,” Penichet-Paul told Quartz. “When we provide proper services to our Border Patrol workforce, I believe we can help improve conditions for everyone, including migrants, at the southern border. We must do what we can to help, because helping prevent even just one death is worth it.”

With additional reporting by Lila MacLellan