Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the second woman to serve on the United States’ highest court, died on Sept. 18, 2020, from pancreatic cancer complications. She was 87. Over the course of her career, Ginsburg shared many lessons in how she saw and navigated the world. Here is one of them.

US Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg isn’t easily stumped. But when asked to pick her greatest professional victory, she hesitates because there are many and, as she put it recently, “It’s like asking which of my grandchildren is dearest to me.”

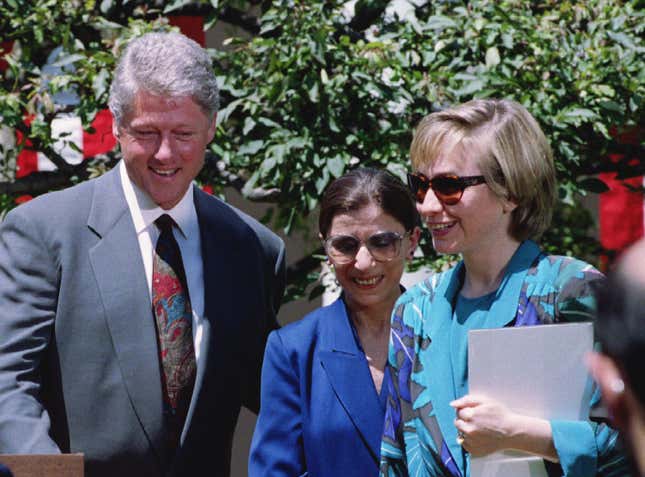

Ginsburg was speaking at the Georgetown University Law Center in Washington, DC on Oct. 30, along with Bill Clinton, the president who nominated her to the high court in 1993, and former secretary of state Hillary Clinton, who quipped that she liked to think she played “a convincing role” in getting him to make that choice.

Hillary had followed Ginsburg’s legal career since law school. “I knew what a difference her pioneering work in gender made,” she said of Ginsburg.

She recalled the “insults and disadvantages” women faced when she began working in the 70s. For example, as a lawyer in private practice, Hillary was earning more than Bill in public service but couldn’t get a personal credit card because of her gender.

Yet Ginsburg proved as an advocate and later a judge that she had “a clear-eyed view” of trying to make the constitution work for everyone. “I always knew she would make a great Supreme Court justice,” Hillary laughed. “I just couldn’t predict that she’d become a cultural icon, the Notorious RBG.”

Ginsburg, for her part, did eventually reveal professional highlights. She cited a landmark 1996 Supreme Court case that struck down male-only admissions at the Virginia Military Institute as a favorite. The justice wrote the majority opinion in that matter.

But it’s actually a case where she dissented that seems to be the dearest grandchild, as it were, pleasing her most of all. Briefly but with relish, Ginsburg told the story of the 2007 wage discrimination dispute, Lilly Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company.

Ledbetter worked for Goodyear in Alabama, the only woman serving as an area manager. She was paid substantially less than her 15 male counterparts over the years. The discrepancy wasn’t based on poor performance, so she sued. Ultimately, the justices ruled that Ledbetter missed the chance to seek relief because she didn’t file a timely claim.

The statute protecting employees from workplace discrimination, Title VII, provided that a claim had to be filed within 180 days after an alleged unlawful employment practice occurred. Ledbetter had been underpaid for years, so the court majority reasoned that she should have sued earlier in her nearly 10-year tenure, although the discrimination only became apparent to Ledbetter later.

In her dissent, Ginsburg pointed out that the unlawful employment practice of paying Ledbetter less because of her gender happened with every paycheck. Thus, Ledbetter was entitled to sue as long as it was within 180 days of a paycheck. In the last line, she opined that lawmakers should correct her colleagues.

“I urged Congress to adopt a new view and it did,” Ginsburg said gleefully, the pleasure evident in her voice and face as she remembered the moment of her vindication a decade later.

In 2009, legislators passed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, the first law approved under Barack Obama’s presidency. Ginsburg still has a copy of the framed bill on the wall in her high court chambers, a poignant reminder that the greatest victories can be those we snatch from the jaws of defeat.