China’s surging property market might finally have hit the skids.

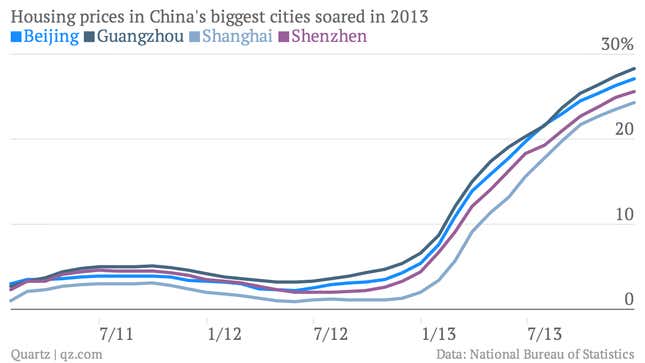

Sales have “showed a sharp decline” (paywall) in January, compared to Dec. 2013, according to China Confidential, a Financial Times research outfit, even when controlling for softness due to the Chinese New Year holiday. Official data show prices still high in December (the last month for which data were available), but those will likely be dragged down in the coming months.

A big blow to global markets

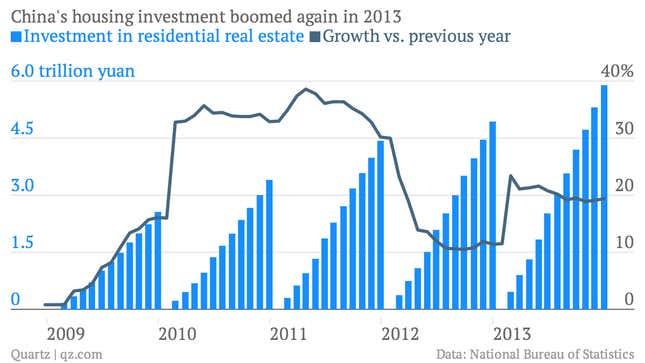

Housing investment is a big engine of China’s economy. And though slower growth could help end China’s dangerous reliance on credit-backed investment, an abrupt slowdown will freak out global markets and throttle commodity prices.

Devastating for China’s financial system

Property-sector loans accounted for one-third of total loans last year, equaling $380 billion. A slowdown would mean that real estate developers, many of whom borrow through shadow finance channels, would struggle to pay back retail investors who effectively loaned to them via wealth management products (more on those here). A lot of that investment has flowed one way or another through China’s shadow banking system, the unregulated credit that allows banks to shunt loans to dodgy borrowers.

But the threat to China’s financial system is much broader than that. Untold billions in corporate borrowing are supported by property used as collateral. There’s a cottage industry of auditors willing to appraise unoccupied or under-development property at whatever value is deemed necessary to get a bank manager to extend a loan. (In many cases, the borrower will turn around and lend to another business at a higher interest rate.) The fact that prices keep going up means there’s nothing challenging those face-value assumptions. A slump in prices would put a big dent in the value of that collateral.

A nightmare for Chinese households

Because the Chinese government doesn’t let households invest in much else, they hold an inordinate amount of their savings in property—more than 66% of family assets were tied up in housing last year, according to Bloomberg.

Mortgage debt—something that many assume is low in China—now claims a 30% share of disposable income, up from 18% in 2008, reports Bloomberg. And that’s just official mortgages; bankers have lately been extending mortgages through other forms of consumer loans.

“A fall in housing prices could have significant knock-on effects on private consumption,” Eswar Prasad, a Cornell University professor, told Bloomberg. “Such a hit to private consumption could pose significant macroeconomic risks, both to headline growth and the process of rebalancing growth.”

A housing market recovery is also likely to be much more excruciating than, say, the US’s, since renting erodes a home’s resale value. China has a distressingly huge oversupply of housing, as we reported in Oct. 2013; in some cities home ownership could be as high as 200%. Worse, the rapid pace at which China’s population is aging is likely to douse demand even more.