For critics of the financial industry, just about every big bank is a “bad bank.”

But a so-called bad bank is also a semi-technical term that describes a special division at a financial institution that happens to be packed with toxic assets, unwanted loans or entire business units hived off from a banking group’s “core” operations. Banks euphemistically dub these units “non-core,” “non-strategic” or a host of other names, steering investors away from considering them part of a bank’s future (and generating increasingly impenetrable earning reports in the process). This is how Lloyds Banking Group recently described its internal bad bank:

The non-core portfolios consist of businesses which deliver below-hurdle returns, which are outside the group’s risk appetite or may be distressed, are subscale or have an unclear value proposition, or have a poor fit with the group’s customer strategy.

It isn’t easy for executives to admit that parts of their companies are rotten; indeed, some big banks do not explicitly identify any aspect of their operations as ripe for reduction, even as nearly all of the key players in the industry shed risk and focus their operations in response to choppy markets and stricter new regulations. Some holdouts are now succumbing; big Italian banks are reportedly drawing up plans to separate their sour loans into separate divisions in the near future.

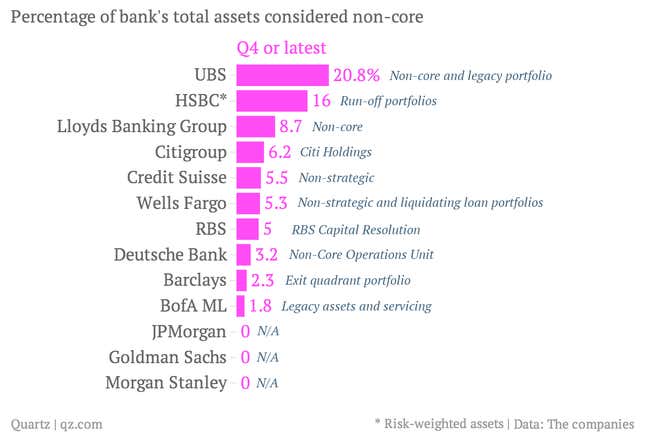

For the banks that have already quarantined unwanted assets in non-core units, UBS stands out as particularly aggressive; its “non-core and legacy portfolio” comprised a fifth of its total assets at the end of last year. According to some number-crunching by Quartz on a selection of Western banks, this is the largest share of bad bank-bound assets among the industry leaders. But RBS gets kudos referring to its non-core division, known as RBS Capital Resolution, as its “internal bad bank” in company communications. No other banks are brave enough to use the “b” word to describe any of their assets, however toxic they may be.

And this is not simply a matter of definitions. While banks seek to de-emphasize ailing units as “non-core,” regulators still require these financial institutions to maintain enough capital to provide an adequate cushion should losses from those zombie loans and securities worsen. The more capital that banks are forced to salt away, the more constricted they are in writing new loans. And since lending is the fuel that powers modern economic engines, less credit usually means less growth, as Europe knows all too well.